Pathway and method of forest health assessment using remote sensing technology

-

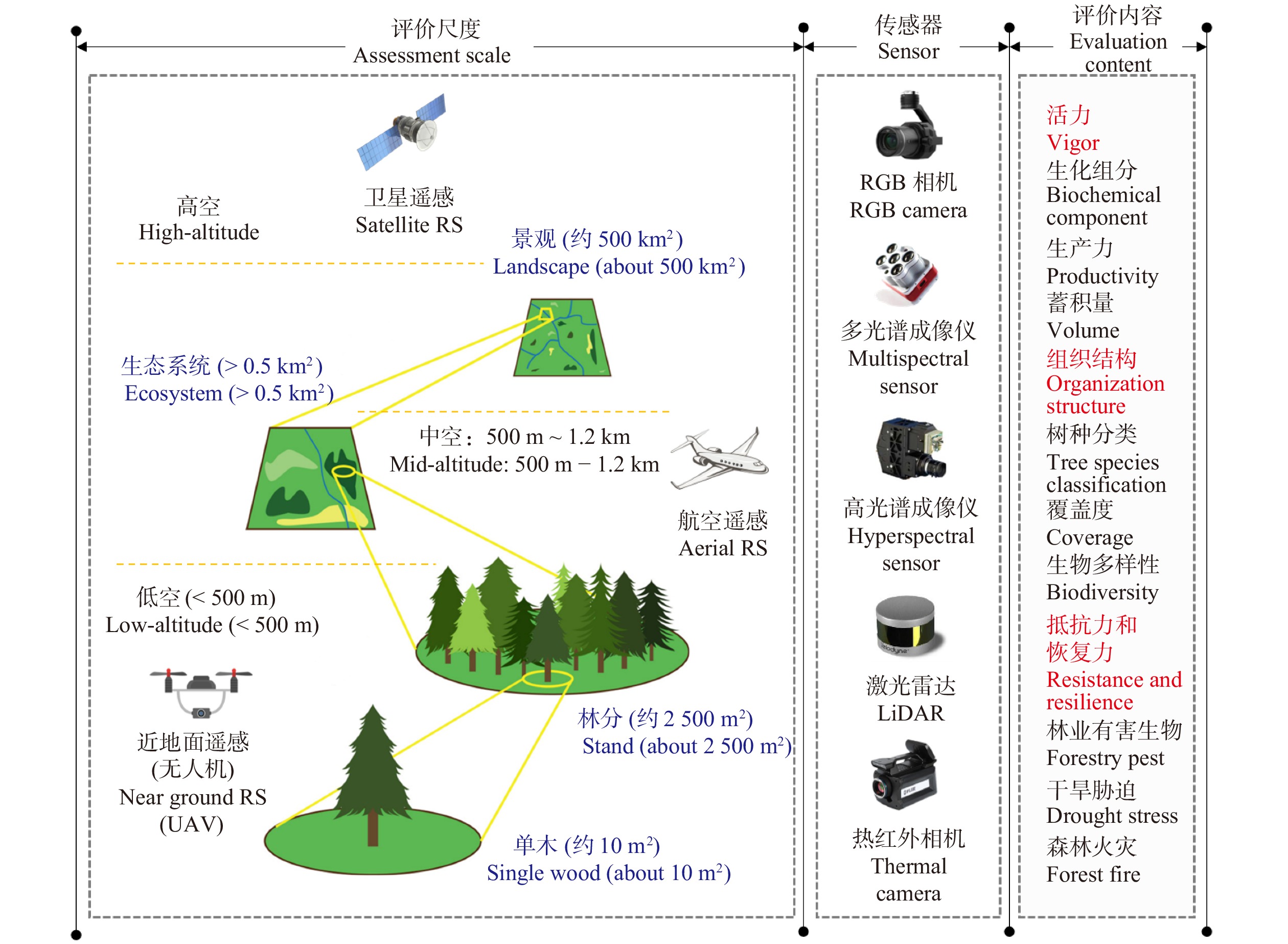

摘要: 近年来,随着气候变化和人类活动的加剧,全球森林面积持续减少、质量下降,生态环境事件频发,森林健康的问题受到前所未有的关注,已经成为生态文明战略的重要组成部分。我国森林资源持续增长,但同时也面临一些问题,如:造林结构单一、林分质量不高、生态稳定性弱等,如何系统准确评价其森林健康状况仍然是当前难点。相对于传统地面调查方法,遥感技术具有实时获取、重复监测以及多时空尺度等优势,并且随着高分遥感和人工智能等技术的飞速发展,大幅提高了解决森林健康评价难题的能力。为系统评估新型遥感技术应用于评价森林健康的潜力,本文在文献分析基础上,指出了现有路径和方法,具体包括:(1)通过文献计量学方法分析并明确了森林健康评价的4大核心内容(活力、组织结构、抵抗力和恢复力)和4大关键问题(树种分类、林木活力、林业有害生物、干旱胁迫)。(2)从不同尺度(单木−林分−生态系统−景观)、不同平台(近地面遥感−航空遥感−卫星遥感)和不同传感器(包括RGB相机、多/高光谱相机、激光雷达、热红外相机、微波雷达和叶绿素荧光扫描仪)3个角度,系统梳理现有遥感技术的优缺点。(3)围绕4个关键问题,阐述近年来应用遥感技术评价森林健康的路径和方法。进一步,本文指出了包括多数据源融合分析、森林健康监测网络与近地面遥感、森林健康大数据应用在内的挑战与机遇,以期为我国森林资源智慧管理提供参考。Abstract: In recent years, with the aggravation of climate change and human activities, the global forest area continues to reduce, forest quality keeps declining, and the ecological and environmental events occur frequently. Thus, forest health issues have received unprecedented attention, and have become an important part of the ecological civilization strategy. China’s forest resources continue to grow, but it also faces some problems, such as single afforestation structure, low stand quality and weak ecological stability. How to evaluate forest health systematically and accurately is still a difficult problem. Compared with the traditional ground survey methods, remote sensing technology has the advantages of macroscopic, timeliness and economic efficiency. With the rapid development of high-resolution remote sensing and artificial intelligence technology, it is possible to overcome the problem of forest health assessment. In order to systematically evaluate the potential of new remote sensing technology, this paper points out the existing paths and methods on the basis of literature analysis, including: (1) through bibliometric analysis, four core contents of forest health assessment (vitality, organizational structure, resistance and resilience) and four key issues (tree species classification, forest vitality, forest pests, drought threat) were identified. (2) Systematically interpreting the advantages and disadvantages of existing remote sensing technologies from three angles, namely, different scales (single tree stand ecosystem landscape), different platforms (near ground remote sensing, aerial remote sensing satellite remote sensing) and different sensors (including RGB cameras, multi/hyperspectral cameras, lidar, thermal infrared cameras, microwave radars and chlorophyll fluorescence scanners). (3) Focusing on four key issues, this paper expounds the application path and method of remote sensing technology to evaluate forest health in recent years. Furthermore, this paper points out the challenges and opportunities, including multi-source fusion analysis, forest health monitoring network and near ground remote sensing, forest health big data application, in order to provide reference for the intelligent management of forest resources in China.

-

Keywords:

- forest health /

- remote sensing /

- sensor /

- VOR system /

- forestry pest

-

森林是陆地生态系统的主体,是林业可持续发展的根本,也是国民经济、社会发展的重要基础。近年来,随着气候变化和人类活动的加剧,全球森林面积持续减少、质量下降,生态环境事件频发,森林健康的问题受到前所未有的关注。国家林业和草原局高度重视森林健康战略的研究和实施,提出:“应对特定历史环境所带来的挑战,树立科学发展观,实施森林健康战略,保持森林生态系统及其服务功能的长期健康稳定,应是我国林业今后发展的必然选择”[1]。同时,也体现目前林业关于“生态安全”“生态建设”“生态文明”的准确定位[2]。我国人工林面积居世界首位,改革开放以来,我国的造林工程取得了举世瞩目的成就,同时也面临一些问题,例如:造林结构单一、林分质量不高、生态稳定性弱等[3]。对森林健康状况的准确、客观评价对我国实施森林健康战略具有重要指导价值。在新的历史时期下,开展精准的森林健康监测是践行“两山”理念,维护全球生命共同体,统筹山水林田湖草系统治理的重要实践。

森林健康评价应该以清晰明确的概念框架、充分有效的数据信息、正确合理的路径方法为基础。具体评估的计算方法较多,前人已进行了细致的总结,本文不再赘述。主要包括:指示物种类群评价法、指标体系法、健康距离法、主成分分析法、聚类分析法、层次分析法、模糊综合评价法、人工神经网络法、多元线性回归法、灰色关联度分析法等[4-5]。而数据收集是所有步骤的关键,也是评价的前提。参考国家林业和草原局在2020年提出的《森林健康监测评价技术规程》,目前林业上主要通过样地设置、每木检尺、生长锥测定、小样方调查和人为分级等手段来进行森林健康状况的诊断和评估。然而,地面调查代价高昂且时空观测尺度不足,无法以低成本、高频率在大面积上反复获取森林的标准化信息[6]。相比之下,遥感技术具有实时获取、重复监测以及多时空尺度等优势。自20世纪30年代人们首次利用航空摄影观察铁杉尺蠖(hemlock looper)危害的落叶林以来[7],遥感技术的应用始终是森林健康评价领域的热点和前沿。回顾以往的研究,前人已经围绕森林健康评价中的森林资源调查、生态功能评估、健康风险控制等内容,从遥感植被参数、生态系统监测、评价指标体系、光谱驱动因素和数据预测模型等方面进行了系统综述[8-14]。尽管如此,考虑到我国森林健康评价的战略价值,目前仍缺乏应用新兴遥感技术聚焦这一研究领域的相关综述。

这是一个技术爆炸的时代,是遥感技术发生深刻转变的时代,丰富的高分遥感数据源、日新月异的机载、星载传感器,以及大数据、物联网和人工智能的发展,为攻克森林健康评价领域的各关键问题提供了新的路径和方法——近年来相关研究数量正急剧增长。基于此,本文根据我国森林健康评价的实践需要:(1)通过文献计量学梳理森林健康的核心内容,提出影响森林健康的若干关键问题;(2)介绍遥感评价森林健康的几个尺度和监测平台,归纳不同类型传感器的技术优势和评价内容;(3)围绕主导森林健康的4个关键问题,即树种分类、林木活力(重点关注林木生化组分、生产力、蓄积量)、生物胁迫(以林业有害生物为以)和非生物胁迫(以干旱胁迫为例),阐述遥感技术的应用路径和方法。综合上述3点,探讨本研究领域的挑战与机遇。

1. 森林健康评价的核心内容

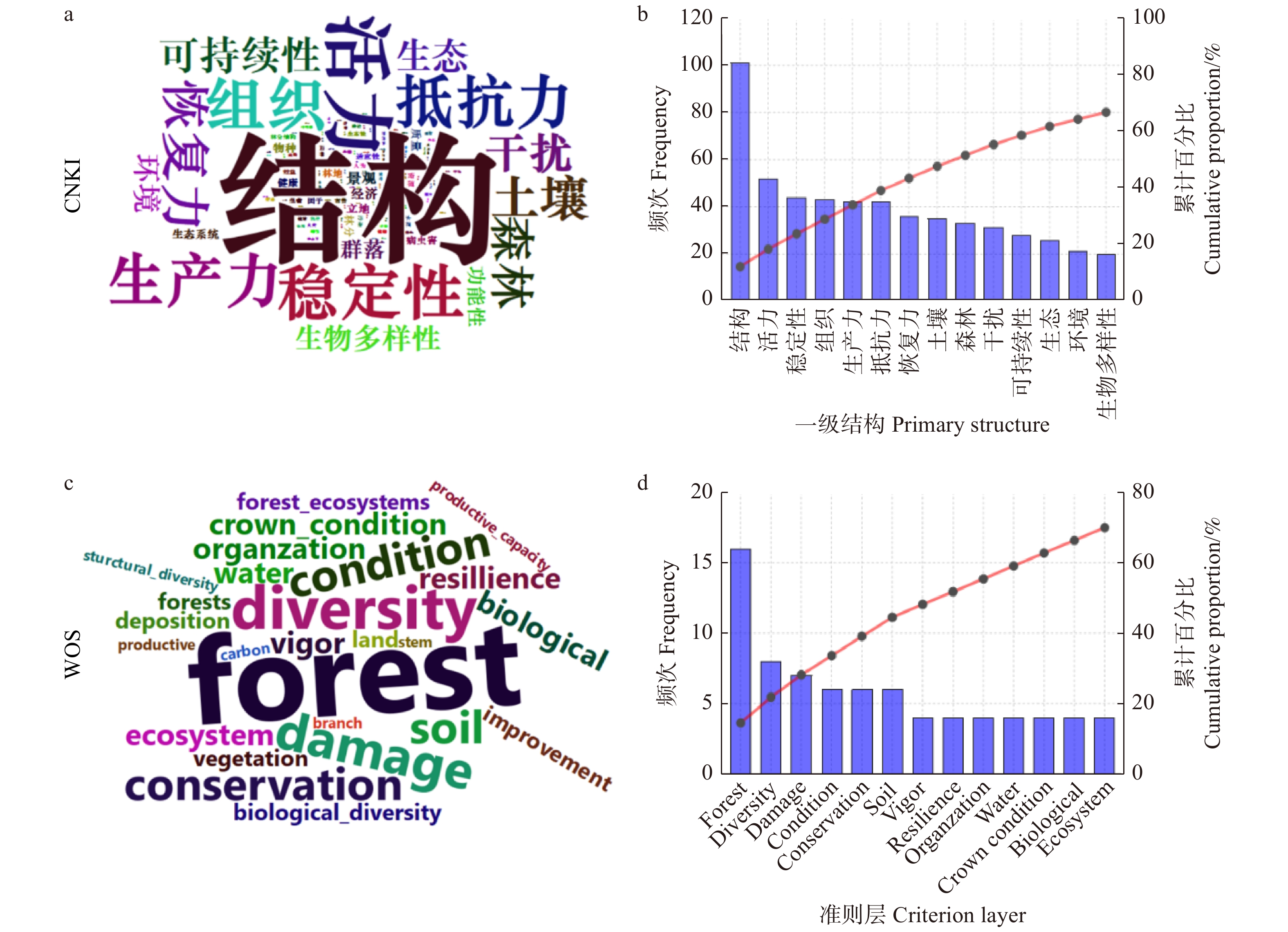

森林健康的内涵受价值观左右,概念的界定外延性强,蕴含生态系统本身属性、社会经济因素、人类价值取向3方面思想。其中,具代表性的定义就达19种[15]。以森林健康(forest health)为篇名检索词,发现Web of Science(WOS)和中国知网(CNKI)数据库中,近40年间分别有1 213篇中文文献和545篇英文文献,可见森林健康问题是一研究热点。本研究进一步从文献计量学的角度,分别从CNKI和WOS数据库中检索具有明确森林健康评价体系的国内外研究。在CNKI中以“森林健康评价”“森林生态系统健康评价”等为主题检索词,检索出中文文献175篇。在WOS中以“forest health assessment”“forest health evaluation”“criteria”“framework”“system”“indicator”等为主题检索词,检索出国外文献23篇。通过其评价指标体系一级结构(primary structure)和准则层(criterion layer)的词频分析(图1),得到高频词为:(1)组织和结构(144次);(2)活力(涵盖生产力,94次);(3)抵抗力和恢复力(涵盖稳定性、可持续性和干扰,153次)。简而言之,目前国内采用的一级结构基本符合Costanza[16]提出的VOR体系3个内容:活力(vigor)、组织结构(organization)、抵抗力和恢复力(resilience)(图1a、b)。与此同时,国外采用的准则层除了包含VOR体系之外,更关注多样性(diversity)、损害(damage)、树冠状态(crown condition)、土壤(soil)和水(water)等内容(图1c、d)。

因此,本文从VOR体系出发,综合考虑国内外森林健康评价指标体系的核心内容,提出4个主导森林健康的关键因子,构建逻辑关系:(1)有效的树种分类是计算森林生物多样性(diversity)的前提。同时也是评价森林的树种配置是否符合“适地适树”造林原则的基础,表征森林的组织结构(organization)。(2)定量提取林木生化组分、生产力和蓄积量是评价森林生态系统功能和经营管理目标的核心内容,关系森林的活力(vigor);(3)监测生物胁迫;(4)非生物胁迫分别是探究影响森林健康直接因素和驱动因子的重要突破,涉及损害(damage)、树冠状态(crown condition)、土壤(soil)和水(water)等具体指标的量化,展现森林的抵抗力和恢复力(resilience)。本文以树种分类、林木活力和我国森林面临的最主要生物、非生物胁迫——林业有害生物和干旱胁迫为主进行综述。

2. 遥感评价森林健康的尺度和传感器类型

从可见光(VIS)、近红外(NIR)、短波红外(SWIR)再到微波(MW),大量研究表明森林在不同波段的电磁波信息与其物种组成、结构和功能具有良好的相关性[13,17]。遥感技术应用各类传感器采集上述电磁波信息,通过数据传输、变换和处理,定量地揭示森林的健康状态。因此,传感器是核心部件。近年来,伴随着遥感数据的时空、光谱分辨率不断提高,特别是搭载平台的发展以及RGB相机、多(高)光谱成像仪、热红外相机、激光雷达、微波雷达和叶绿素荧光扫描仪等新兴传感器的日趋成熟,遥感技术在森林健康评价领域展现出强大的生命力,本文系统梳理了现有各类传感器的优缺点(表1)。

表 1 不同传感器在森林健康评价中的技术优势和主要评价内容Table 1. Advantages and application of different sensors in forest health assessment传感器

Sensor技术优势

Technical advantage主要不足

Main shortcomings特征参量

Feature parameter评价内容

Assessment contentRGB高分相机

RGB high-resolution camera低成本、高空间分辨率

Low cost, high spatial resolution成像质量受光照条件影响大、光谱信息有限

Image quality is influenced by illumination conditions, limited spectral informationRGB图像、纹理

RGB image, texture普适性好,一般作为遥感底图或摄影测量数据

Widely used as RS base map or photogrammetric data多光谱成像仪

Multispectral sensor几个波段的反射率

Reflectance of several bands异物同谱、同物异谱问题使数据解译困难

Difficult data interpretation due to synonyms spectrum多光谱图像、多通道反射率

Multispectral image, multi-channel reflectance树种分类、主要生化组分、物候、胁迫

Tree species classification, main biochemical components, phenology, stress高光谱成像仪

Hyperspectral sensor上百个窄波段的反射率

Reflectance of hundreds of narrow bands观测条件严格、数据量大、分析难度大

Strict observation condition and difficult data analysis图谱立方体

Hyperspectral cube树种分类、多种生化组分、光合作用、物候、早期胁迫

Tree species classification, photosynthesis, various biochemical components, phenology, early stress热红外相机

Thermal camera全天候、穿透性、精细温差

All weather, penetrating, fine temperature difference温度变化易受周围环境影响

Temperature variation is easily affected by the surrounding environment方向亮度温度、热红外图像

Directional brightness temperature, thermal infrared image森林火灾、森林干旱、光合作用、早期胁迫

Forest fire, drought, photosynthesis, early stress激光雷达

LiDAR穿透性、精细的地形和森林三维信息

Penetrating, fine terrain and 3D forest information缺少光谱、纹理信息

Lack of spectral and texture information点云廓线、波形

Point cloud profile, waveform地形、位置、生物量、蓄积量、冠层结构、叶面积指数

Topography, location, biomass, volume, canopy structure, LAI微波雷达

Microwave radar全天候,一定穿透性,可达地下

All weather, limited penetrating, reaching underground斑点噪声大、受地形影响

严重

Speckle noise and seriously affected by terrain后向散射、干涉系数、极化雷达图像

Backscattering, interference coefficient, polarimetric radar image地形、生物量、蓄积量、水分、土壤

Topography, biomass, volume, moisture, soil叶绿素荧光扫描仪

Chlorophyll fluorescence scanner获取日光诱导的叶绿素信息

Capturing chlorophyll information induced by sunlight受大气影响大、时空连续性有限

Affected by atmosphere, limited space-time continuity荧光参数、光化学效率

Fluorescence parameters, photochemical efficiency初级生产力、碳循环、物候、早期胁迫

Primary productivity, carbon cycle, phenology, early stress从评价维度上看,森林健康的评价内容是分层次、分尺度的——森林的空间格局和异质性取决于观测的尺度。应用遥感技术时需考虑4个尺度:第一是林木个体的健康,这是所有健康的基础;其次是林分(群落尺度)的健康,这是健康的关键;第三是森林生态系统的健康,这是健康的目的;第四是景观的健康,这是健康的体现。在同一评价尺度(空间分辨率)下,传感器的光谱分辨率和时间分辨率分别有着不同的贡献。目前,利用近地面无人机、中空载人机和高空卫星等平台搭载多种传感器,可实现对森林活力、组织结构、抵抗力和恢复力三大内容高频次、长时序和多尺度的立体观测,为其健康评价提供详实的观测资料(图2)。

3. 遥感评价森林健康的关键问题

3.1 树种分类

森林健康的客观评价首先依赖于准确的树种组成及其空间分布信息。Felbermeier等[18]分析了发给林业工作者的347份调查问卷。三分之二的受访者认为森林信息不足,其中九成期望应用遥感来改善。在63个森林参数中,树种分类的关注度排名第一。

林业中的树种组成往往根据特定树种的蓄积量或胸高断面积占比来定义,然而,从遥感的角度通常将林木组成描述为图像上特定树种冠层覆盖百分比[19]。早期基于全色、多光谱的光学遥感是开展树种分类研究的主要数据源,但分类精度受限于光谱分辨率。高光谱遥感的兴起打破了这种局面。据统计,近20年来应用遥感技术进行树种分类的研究,超过三分之一使用了高光谱数据[20]。从350 nm到2 500 nm,几十至上百个相邻通道的窄波段反射率信息可以充分展现不同树种的形态特征和理化性质,这是进行树种分类的依据[21]。具体而言,树冠在不同波段的反射率与:(1)叶组织的化学性质(水、光合色素、结构性碳水化合物);(2)叶形态(细胞壁厚度、气腔、角质层蜡)[22-23];(3)树冠结构(枝、叶密度、角度分布、聚集情况)以及树体大小、叶面积指数等森林植被参数有关[24]。得益于近地面无人机高光谱成像系统厘米级的空间分辨率,目前能够实现单木尺度精细的树种信息提取。尽管如此,机载高光谱遥感的使用成本仍然较高,同时易受到气象条件影响,目前未能广泛投入林业应用。

理论上,不同树种具有不同的光谱特征。但由于自然林、混交林的复杂性和观测条件的不稳定性,仅使用单一的光谱特征难免遭遇“异物同谱”和“同物异谱”的问题[25]。此时,纹理特征可用于改善树种分类的精度,它通常反映与图像色调变化相关的局部空间信息[26]。Franklin等[27]研究表明,纹理层可提高10% ~ 15%的分类精度。树冠内部阴影、叶片特征和分枝都是产生单木尺度纹理差异的主要因素[28],而在林分尺度上则由树冠形状、树种组成、郁闭度等因素影响[29]。目前,最常用的纹理特征提取方法是灰度共生矩阵(GLCM)。除纹理信息之外,森林丰富的季节物候变化特征(如北方落叶林春季返青,秋季褪绿、落叶等)可作为树种分类的另一重要先验知识[30]。由于林木的物候因物种而异,多个物候期的组合将带来更为细致的种间差异。因此,融合多时相遥感数据,同时在恰当的时间窗口采集数据(例如避开晚秋大部分树木落叶的情形)有利于提高树种分类精度[31]。近年来,随着计算机技术尤其是人工智能领域的不断发展,深度学习可以有效弥补传统树种分类算法的不足,在高光谱影像处理领域中表现出色。研究发现,利用深度学习网络提取的判别特征可以显著提高对高光谱影像的物种分类性能[32]。徐岩等[33]收集了近15年来利用高光谱遥感对植物进行物种识别的66个案例。使用Wilcoxon符号秩检验发现,在不同的待分类物种数量下,深度学习的分类精度均显著高于非深度学习。

目前,多遥感数据源融合是树种分类研究领域的发展趋势。其中较为典型的是将表征冠层水平方向光谱信息的高光谱图像(HI)与表征林分三维结构信息的激光雷达点云(point cloud)融合[34]。高光谱图像在光谱维度方面能达到纳米级分辨率,可提供林木反射率细节,根据光谱差异分析不同的物种组成;激光雷达可通过激光束穿透植被冠层,生成密集点云数据,这些信息的几何部分与树冠、分枝和叶形的结构有关[35-36],后向散射信号的强度与叶片的类型[37]、大小、方向和密度有关[38-39]。黄华国[40]分析了激光雷达的主要传感器类型和2种数据结构(波形和点云),系统总结了主要森林参数的提取方法,包括波形分析、点云分析、参数预测和数据融合。将激光雷达和高光谱两者融合可实现数据优势互补,增强遥感技术直接识别树种的应用效果[41]。

一个完整的树种分类工作包括数据获取、单木分割、特征约简、执行分类、精度检验5步[42-43]。其中,单木分割是关键步骤。对于被动光学遥感来说,基于对象分类(object-oriented)的多尺度分割是目前应用最广泛的一种自下而上的区域融合技术[44],其有效避免了基于像元分类导致的结果的破碎化(“椒盐效应”)[45]。对于激光雷达等主动遥感来说,基于点云生产的冠层高度模型(CHM)结合局部极大值、模板匹配、区域生长和分水岭分割等算法可以实现单木自动分割[46]。

3.2 林木活力

活力是指森林生态系统的能量或活性,可以用其物质生产量或能量固定效率来衡量,也可以用光合效率、光合产物或地上生物量等指标来评价[47]。从遥感可获取数据的角度上看,森林的活力涵盖林木生化组分、生产力和蓄积量等,这些都是体现森林生态功能的重要内容。农业上作物活力(长势)的遥感监测研究和应用很成熟[48-50]。这主要是由于作物通常群落结构、单株特征均一性高、植物多样性简单、干扰因素较少、监测窗口期(适合传感器收集数据的时间段)稳定,因此这方面业务化能力和监测精度都较高。相比之下,森林群落结构异质性强,植物多样性复杂,加上单株特征丰富、地形多变(山高、坡陡、沟深),监测窗口期多变。可以说,林木活力的监测难度远比作物要大。

森林生态过程中,诸如光合作用、养分循环、蒸发、蒸散、初级生产、废物分解等,都和林木生化组分密切相关。应用光学遥感测定林木生化组分主要有两种途径:(1)建立反演生化组分的辐射传输模型(RTM)。黄华国[51-52]总结了林业定量遥感的辐射传输模型,例如针叶尺度的Prospect、Liberty以及冠层尺度的DART、RAPID、LESS等都能实现林木生化组分的反演。(2)通过经验统计分析,利用植被指数经过回归或非参数化模型(如人工神经网络、支持向量机、随机森林等)估算生化组分。Paul[53]总结了植物在可见光和近红外波段(430 ~ 2 350 nm)共42个光谱吸收特征与电子跃迁、化学键及特定化学成分的对应关系。德国波恩大学Verena Henrich发起的IDB项目(Index Data Base,www.indexdatabase.de)提供了一个广泛覆盖各类传感器的植被指数库,其中包含大量可估算林木生化组分的植被指数。早期卫星遥感技术主要用于反演大尺度的、叶片中含量较高的主要生化组分,如叶绿素[54]和类胡萝卜素[55]。高光谱遥感技术的发展促使定量反演森林中各类生化组分成为可能,除叶绿素a、b,类胡萝卜素α、β之外[56-58],木质素[59-60]、纤维素[61]、含水量[62]、多酚[63]、淀粉、糖[64],氮、磷、钾、镁、钙等元素等[65-66]均能被精确提取。近年来,融合高光谱与激光雷达数据的生化组分反演研究日益增长,一方面使得遥感可以获取单木水平的生化组分,另一方面能够从反演方法上消除冠层结构对生化组分反演的干扰。

森林生产力(GPP)表征其内部生态系统的物质生产和能量流动,其测定直接影响森林经营管理策略。应用遥感评价森林生产力主要有两种途径:(1)基于植被指数的统计模型:以“绿度”植被指数NDVI为代表的光学遥感在过去30年间极大地促进了人们在宏观尺度认识和理解森林生态系统[67]。(2)基于经典的光能利用率模型:如MODIS-GPP、Glo-Pem、C-Fix、VPM、EC-LUE等。Potter等[68]提出的CASA模型证明了光学遥感具备反演森林生产力的潜力。然而,通过“绿度”实质上是探测植物“潜在”的光合作用。同时,这种估测在密集森林易受“饱和效应”的影响,对环境胁迫诱导的光合反应变化也不敏感[69]。日光诱导叶绿素荧光(SIF)的提出为森林生产力的直接估测提供了可靠的一种方法[70]。与传统的植被指数相比,SIF能更直接地揭示植物的实际光合作用状况,更早地监测植被健康状况变化以及环境胁迫的影响[71-72]。2011年以来,大量研究利用GOSAT、Gome-2和SCIAMACHY、OCO-2等传感器,已成功反演了全球尺度的SIF遥感数据[73-74]。此外,2017年发射的Sentinel-5P(搭载Tropomi传感器)和计划于2022年发射的Flex卫星(搭载Floris传感器)都可为SIF的反演提供丰富的原始数据。

森林蓄积量的估测是国家森林资源清查的主要目的之一,为经营和采伐提供了重要依据。目前主要通过光学遥感(如Landsat TM/ETM/OLI、MODIS、SPOT5、高分系列)、合成孔径雷达(SAR)(如Terra-SAR、ALOS、PALSAR)和激光雷达对森林的蓄积量进行估测。其中,激光雷达的精度最高,适用于小区域的森林蓄积量调查[75]。光学遥感获取的则主要是森林冠层表面的信息,在森林高度、蓄积量等定量估测方面有其局限性[76]。合成孔径雷达具备全天时、全天候的观测能力,且波长相对较长,对于森林等植被叶簇具有一定的穿透能力,因此可获取与森林垂直结构参数更相关的遥感观测量[77]。该领域主要包括3种蓄积量估测方式:(1)极化SAR、(2)干涉、极化干涉SAR和(3)层析SAR。此外,利用无人机摄影测量技术(如运动恢复结构)获取森林数字表面模型(DSM)和数字地形模型(DEM),提取树高、冠幅后参照二元立木材积模型也可估算森林蓄积量[78]。

3.3 林业有害生物

全球每年约有65.3%的森林面积受到各种林业有害生物不同程度的影响。在我国,林业有害生物的发生呈现出持续的高发频发态势,具有传播速度快、发生面积大、危害程度重等特征,常年发生约1.2 × 107 hm2,经济损失1 100亿元。林业有害生物的遥感监测是有效防控之急需。

林木遭受林业有害生物危害之后,外部树冠表现为落叶、失叶、卷叶、病斑、叶片变色、枝梢枯萎等受害状,从而引起整个树冠颜色、结构和叶面积指数的改变;内部生理表现为叶片细胞结构遭到破坏,色素、水分丧失、营养传输受阻,光合作用、呼吸作用和蒸腾作用等功能的衰退,从而引起叶片颜色、温度、叶绿素荧光等变化[79-82]。通常来说,应用遥感获取的森林的光谱数据偏向代表林木树冠上层特征,尽管有限,但却能将树冠状况与森林健康联系起来。以树冠变色为例:在北美和欧洲分别暴发成灾的中欧山松大小蠹(Dendroctonus ponderosae)和云杉八齿小蠹(Ips typographus)的危害可大致划分为3个阶段:(1)绿色攻击,树冠保持绿色,肉眼难以发觉;(2)红色攻击,林木边材水分散失,叶片细胞组织结构被破坏,色素被分解,颜色逐步由绿变黄再转为红色;(3)灰色攻击,树冠大部分叶片逐渐脱落,整株树失水枯萎[83-84]。大量研究使用不同的光学遥感数据监测上述树冠变色。据Senf等[17]统计,13%的研究应用低分辨率数据(其中MODIS占75%),主要绘制食叶害虫的危害;57%的研究应用中分辨率数据(其中Landsat系列占83%),适合绘制所有昆虫类型的干扰;30%的研究应用高分辨率数据(以HyMap、QuickBird、RapidEye和WorldView为主)和极高分辨率数据(包括7%的激光雷达和机载高光谱影像),主要绘制小蠹的危害。

使用地物光谱仪的研究证实了高光谱遥感检测林木胁迫的能力——将光谱响应与3种主要的叶片光合色素(叶绿素、类胡萝卜素和花青素)的浓度变化联系起来[85-86]。一些研究使用可覆盖更宽波段(如短波红外)的传感器,从而揭示出早期攻击阶段对应的水分胁迫信息[87-88]。同时,利用高光谱数据获得三边参数(红边、黄边、蓝边的位置、数值和面积),可反演林业有害生物的胁迫[89]——当林木叶绿素含量高、生长活力旺盛时,“红边”会向长波(红光)方向偏移;当其受有害生物侵染失绿后,“红边”会向短波(蓝光)方向偏移[90-92]。因此,卫星遥感WorldView-3、Sentinel-2等数据源因包含红边波段,且时空分辨率都相对较高,非常适合林业有害生物的监测应用[93-94]。此外,利用多时相卫星遥感图像的时序分析可对有害生物发生的复杂时空动态进行监测,结合监测对象的生物生态学特性,可建立灾害监测模型并揭示成灾机制[95-96]。

近年来,随着云台、惯性测量单元(IMU)和全球导航卫星系统(GNSS)的发展,无人机的空间定位能力和数据采集精度显著提高[97]。尤其是我国北斗导航网络的建成和千寻位置服务的普及,在手机移动网络信号较好的区域,无人机可以实现厘米级的实时空间定位。而在无手机信号的偏远山区,同样可以通过后差分技术获得厘米级的空间位置信息。很多研究使用无人机搭载新型传感器(如高光谱相机、激光雷达、热红外相机等)实现林业有害生物单木尺度精准监测[98-99]。利用不同平台的遥感数据实现寄主树种的自动辨识、危害阶段的智能分级和准实时(near real time)的图像解译上报是这一领域的前进方向。目前,林业有害生物遥感的监测主要存在以下挑战:(1)区分特定有害生物的危害与其他环境胁迫、干扰因素;(2)单木尺度早期危害(绿色攻击)的检测与遥感监测窗口期的确定;(3)在景观、区域尺度及更大地理梯度对林业有害生物的发生、发展驱动因素的探究等。

3.4 干旱胁迫

目前有2种林木非正常死亡的生理机制:水分失衡和碳饥饿[100]。大量研究表明,无论哪种死亡机制,都与干旱胁迫密不可分[100-103]。因此,干旱被认为是持续时间最长,破坏性最强且最不易监测的事件之一[104]。

应用遥感技术可以从几个方面监测森林干旱:(1)叶片的水分在短波红外(SWIR)波段有一个吸收峰,可供光学遥感检测(如构建归一化水分指数NDWI);(2)叶片色素变化和叶面积指数(LAI)的减少可间接地反映干旱程度[105],因此可通过“绿度”实现干旱监测(如构建归一化植被指数NDVI、植被状况指数VCI、增强植被指数EVI等[106];(3)干旱胁迫使林木气孔导度、蒸腾速率降低,由此引起林木光谱在热红外波段变化,多(高)光谱、热红外传感器可以捕捉到这种局部温度的上升[88],通过地表温度、热惯量等参数构建干旱指数,如温度状态指数TCI可以反映林木对温度的响应[107];(4)干旱胁迫诱导启动林木的防御机制,使其光合作用减弱、生长减缓。因此基于植被生理参数的冠层吸收光合有效辐射比(fAPAR)、日光诱导叶绿素荧光(SIF)也可应用于干旱监测[108];(5)如果干旱程度继续增加,酶活性将下降,并可能对叶绿素结构造成损害[109-110],林木落叶并逐渐枯萎,落叶将直接影响叶面积指数的变化。通过前后比较,可以直接评估干旱对森林生态系统的影响[111]。

目前可用于监测干旱的卫星有很多,包括:较低空间分辨率的NOAA系列卫星(搭载AVHRR传感器)、Terra和Aqua卫星(搭载MODIS传感器,开发了诸如EVI、GPP/NPP、MODIS LAI等产品)[112];中空间分辨率的Landsat系列、Sentinel等;高空间分辨率的SPOT-5、GeoEye、WorldView系列、高分系列、珠海一号等卫星,可用于评估典型地块大小的干旱影响,并监测森林生态系统的结构变化[113-114]。此外,许多机载传感器已被开发用于单木尺度干旱胁迫的研究,例如机载可见红外成像光谱仪(AVIRIS)和机载高光谱成像系统(AAHIS)[115]。

4. 挑战与机遇

我们生活在一个“生态贫困”的时代——极端气候事件频发、干旱与生物灾害等环境压力与日俱增,森林健康风险持续增长。与此同时,这也是一个“十倍速”发展的时代——计算机、遥感技术的迭代更新、跨学科的知识融合、人机交互的“技术青春期”为我们更深刻理解森林健康开辟了新的道路。可以说,应用遥感评价森林健康的挑战和机遇并存,具体体现在以下几方面。

4.1 多数据源融合分析

遥感是林业上的“CT”、“核磁”和“测温枪”——能发现森林的“病灶”,能定位;由表及里,能立体成像。但同时应该注意到,遥感观测到的是表象和症状,给出的是倾向性意见[116]。然而,大部分森林健康的影响因素通常是复杂的、多维的、多尺度的、非线性的——并非每一个症状都能归因于一种特定的驱动力[13]。例如,由云杉八齿小蠹危害导致的林木针叶叶绿素减少、光合作用活性降低,相同的症状也可能是由土壤营养不足或酸雨引起的。如同中医望、闻、问、切多方位的诊断,遥感多数据源的融合分析可以从更多的角度刻画森林的健康状态,给出更为客观的评价结果。目前,遥感数据的融合方式包括全色、多光谱、高光谱图像融合(空谱融合)、全色/多光谱与合成孔径雷达图像融合、多光谱/高光谱与激光雷达图像融合以及热红外遥感图像、夜光遥感图像、视频遥感数据和立体遥感图像的融合等[117]。同时,也存在不同平台数据的时空尺度差异问题,不同传感器获取的数据融合问题,同系列卫星遥感的传感器变化问题等。如何开发算法解决多源数据融合问题,充分发挥各种遥感数据的优势,挖掘长时序遥感数据信息,实现森林健康多时相、多尺度的动态监测,是林业工作者必须考虑的问题。

4.2 森林健康监测网络与近地面遥感

森林健康监测网络有着悠久的传统,世界各地都有许多监测项目,例如:(1)德国的三水平监测体系;(2)美国、加拿大等林务局的森林健康监测项目(FHM);(3)我国国家林业与草原局的全国森林资源清查;(4)联合国粮农组织森林资源评估等等。这些监测网络详实的调查数据是遥感进行森林健康评估的重要“底图”,可纳入我国森林健康评价的遥感方案。目前,随着5G通信、物联网(IoT)、无线传感器网络、无人控制系统等新技术的发展,森林健康评价逐渐向基于物联网技术的自动观测、融合地面和遥感观测的多尺度监测发展。各类网络相机、车载相机、智能眼镜、相机诱捕器、平板电脑和智能手机将配备有更为复杂的传感器组合(如多/高光谱、激光雷达、3D热成像或3D深度成像等),结合多样化的植被监测应用程序(如用于识别植物物种的“花伴侣”,用于测定植被叶面积指数的“PocketLAI”,用于模拟高光谱相机的“HawkSpex®mobile”),能够经济、灵活地提取森林健康评价指标。因此,如何将这些地面观测数据——地面真值(ground truth)融入遥感多源森林健康评价网络,完善“天−空−地”立体监测,绘制我国森林健康“一张图”是当前面临的一个重大挑战。

4.3 森林健康大数据应用

目前,林业资源数据和业务数据无论从总量还是种类上都已初具规模——我国国家森林资源智慧管理平台提供了精确到林班级别森林资源调查数据和高分影像。各类大数据服务应运而生。例如2019年雄安森林大数据系统为每棵树创建专属的二维码“身份证”,追溯苗木从初期种植到后期管护的完整过程[118]。谷歌公司推出的Google Earth Engine云计算平台提供了全球尺度的地理空间分析服务[119],可被应用于森林健康指标的提取。凭借其云平台的算力模型,运算速度远超传统方法。此外,美国的森林资源清查和分析(FIA)数据库、全球森林观测网(Globe Forest Watch)、全球树木多样性实验网络(TreeDivNET)等众多数据库提供了广泛的森林基础数据。但是,目前存在“数据丰富,但信息缺乏”的问题。因此,加强挖掘森林健康大数据背后的隐藏价值迫在眉睫。

-

表 1 不同传感器在森林健康评价中的技术优势和主要评价内容

Table 1 Advantages and application of different sensors in forest health assessment

传感器

Sensor技术优势

Technical advantage主要不足

Main shortcomings特征参量

Feature parameter评价内容

Assessment contentRGB高分相机

RGB high-resolution camera低成本、高空间分辨率

Low cost, high spatial resolution成像质量受光照条件影响大、光谱信息有限

Image quality is influenced by illumination conditions, limited spectral informationRGB图像、纹理

RGB image, texture普适性好,一般作为遥感底图或摄影测量数据

Widely used as RS base map or photogrammetric data多光谱成像仪

Multispectral sensor几个波段的反射率

Reflectance of several bands异物同谱、同物异谱问题使数据解译困难

Difficult data interpretation due to synonyms spectrum多光谱图像、多通道反射率

Multispectral image, multi-channel reflectance树种分类、主要生化组分、物候、胁迫

Tree species classification, main biochemical components, phenology, stress高光谱成像仪

Hyperspectral sensor上百个窄波段的反射率

Reflectance of hundreds of narrow bands观测条件严格、数据量大、分析难度大

Strict observation condition and difficult data analysis图谱立方体

Hyperspectral cube树种分类、多种生化组分、光合作用、物候、早期胁迫

Tree species classification, photosynthesis, various biochemical components, phenology, early stress热红外相机

Thermal camera全天候、穿透性、精细温差

All weather, penetrating, fine temperature difference温度变化易受周围环境影响

Temperature variation is easily affected by the surrounding environment方向亮度温度、热红外图像

Directional brightness temperature, thermal infrared image森林火灾、森林干旱、光合作用、早期胁迫

Forest fire, drought, photosynthesis, early stress激光雷达

LiDAR穿透性、精细的地形和森林三维信息

Penetrating, fine terrain and 3D forest information缺少光谱、纹理信息

Lack of spectral and texture information点云廓线、波形

Point cloud profile, waveform地形、位置、生物量、蓄积量、冠层结构、叶面积指数

Topography, location, biomass, volume, canopy structure, LAI微波雷达

Microwave radar全天候,一定穿透性,可达地下

All weather, limited penetrating, reaching underground斑点噪声大、受地形影响

严重

Speckle noise and seriously affected by terrain后向散射、干涉系数、极化雷达图像

Backscattering, interference coefficient, polarimetric radar image地形、生物量、蓄积量、水分、土壤

Topography, biomass, volume, moisture, soil叶绿素荧光扫描仪

Chlorophyll fluorescence scanner获取日光诱导的叶绿素信息

Capturing chlorophyll information induced by sunlight受大气影响大、时空连续性有限

Affected by atmosphere, limited space-time continuity荧光参数、光化学效率

Fluorescence parameters, photochemical efficiency初级生产力、碳循环、物候、早期胁迫

Primary productivity, carbon cycle, phenology, early stress -

[1] 许勤. 绿色就是固碳造林等于减排:记国家林业局造林司司长魏殿生[J]. 林业经济, 2003(2):10−11. Xu Q. Green means carbon sequestration and afforestation equals emission reduction: Wei Diansheng, director of afforestation department of State Forestry Administration[J]. Forestry Economy, 2003(2): 10−11.

[2] 高均凯. 深入研究森林健康积极探索中国森林健康之路[J]. 北京林业管理干部学院学报, 2005(1):22−25. Gao J K. Research on the implementation of forest health strategy in China[J]. State Academy of Forestry Administration Journal, 2005(1): 22−25.

[3] 王云霖. 我国人工林发展研究[J]. 林业资源管理, 2019(1):6−11. Wang Y L. Research on plantation development in China[J]. Forestry Resource Management, 2019(1): 6−11.

[4] 胡爽, 徐誉远, 王本洋. 我国森林健康评价方法综述[J]. 林业与环境科学, 2017, 33(1):90−96. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-4427.2017.01.017 Hu S, Xu Y Y, Wang B Y. Review of forest health monitoring and assessment in China[J]. Forestry and Environmental Science, 2017, 33(1): 90−96. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-4427.2017.01.017

[5] 王秋燕, 陈鹏飞, 李学东, 等. 森林健康评价方法综述[J]. 南京林业大学学报(自然科学版), 2018, 42(2):177−183. Wang Q Y, Chen P F, Li X D, et al. Review of forest health assessment methods[J]. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University (Natural Sciences Edition), 2018, 42(2): 177−183.

[6] Pause M, Schweitzer C, Rosenthal M, et al. In situ/remote sensing integration to assess forest health: a review[J/OL]. Remote Sensing, 2016, 8(6): 471 [2021−01−12]. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8060471.

[7] 金瑞华, 张宏名, 林培. 浅谈生物灾害遥感监测[J]. 遥感信息, 1991(3):35−37. Jin R H, Zhang H M, Lin P. Discussion on remote sensing monitoring of biological disasters[J]. Remote Sensing Information, 1991(3): 35−37.

[8] 高广磊, 信忠保, 丁国栋, 等. 基于遥感技术的森林健康研究综述[J]. 生态学报, 2013, 33(6):1675−1689. doi: 10.5846/stxb201112011838 Gao G L, Xin Z B, Ding G D, et al. Forest health studies based on remote sensing: a review[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2013, 33(6): 1675−1689. doi: 10.5846/stxb201112011838

[9] 何兴元, 任春颖, 陈琳, 等. 森林生态系统遥感监测技术研究进展[J]. 地理科学, 2018, 38(7):997−1011. He X Y, Ren C Y, Chen L, et al. The progress of forest ecosystems monitoring with remote sensing techniques [J]. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 2018, 38(7): 997−1011.

[10] 王彦辉, 肖文发, 张星耀. 森林健康监测与评价的国内外现状和发展趋势[J]. 林业科学, 2007, 43(7):84−91. Wang Y H, Xiao W F, Zhang X Y. Current status and development tendency of forest health monitoring and evaluation[J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2007, 43(7): 84−91.

[11] 马有国, 杜学惠. 森林健康评价的遥感技术研究[J]. 森林工程, 2019, 35(2):37−44. Ma Y G, Du X H. Remote sensing technology for forest health assessment[J]. Forest Engineering, 2019, 35(2): 37−44.

[12] Lausch A, Borg E, Bumberger J, et al. Understanding forest health with remote sensing, part III: requirements for a scalable multi-source forest health monitoring network based on data science approaches[J/OL]. Remote Sensing, 2018, 10(7): 1120 [2021−01−15]. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10071120.

[13] Lausch A, Stefan E, Douglas K, et al. Understanding forest health with remote sensing (I): a review of spectral traits, processes and remote sensing characteristics[J/OL]. Remote Sensing, 2016, 8(10): 1029 [2020−12−19]. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8121029.

[14] Lausch A, Stefan E, Douglas K, et al. Understanding forest health with remote sensing (II): a review of approaches and data models[J/OL]. Remote Sensing, 2017, 9(2): 129 [2020−12−28]. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10071120.

[15] 高均凯. 森林健康基本理论及评价方法研究[D]. 北京: 北京林业大学, 2007. Gao J K. Basic theory and evaluation method of forest health[D]. Beijing: Beijing Forestry University, 2007.

[16] Costanza R. Toward an operational definition of ecosystem health [M]//Costanza R, Norton B G, Haskell B D, eds. Ecosystem health: new goals for environmental management. Washington D C: Island Press, 1992: 239−256.

[17] Senf C, Seidl R, Hostert P. Remote sensing of forest insect disturbances: current state and future directions[J]. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation & Geoinformation, 2017, 60: 49−60.

[18] Felbermeier B, Hahn A, Schneider T. Study on user requirements for remote sensing applications in forestry[C/OL]. ISPRS TC VII Symposium – 100 Years ISPRS. 2010 [2021−02−13]. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas-Schneider-10/publication/266412426_STUDY_ON_USER_REQUIREMENTS_FOR_REMOTE_SENSING_APPLICATIONS_IN_FORESTRY/links/55b6566a08ae092e9655d92c/STUDY-ON-USER-REQUIREMENTS-FOR-REMOTE-SENSING-APPLICATIONS-IN-FORESTRY.pdf.

[19] Fabian E, Hooman L, Krzysztof S, et al. Review of studies on tree species classification from remotely sensed data[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2016, 186: 64−97. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2016.08.013

[20] 孔嘉鑫, 张昭臣, 张健. 基于多源遥感数据的植物物种分类与识别: 研究进展与展望[J]. 生物多样性, 2019, 27(7):796−812. doi: 10.17520/biods.2019197 Kong J X, Zhang Z C, Zhang J. Classification and identification of plant species based on multi-source remote sensing data: research progress and prospect[J]. Biodiversity Science, 2019, 27(7): 796−812. doi: 10.17520/biods.2019197

[21] Ferreira M, Zortea M, Zanotta D, et al. Mapping tree species in tropical seasonal semi-deciduous forests with hyperspectral and multispectral data[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2016, 179: 66−78. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2016.03.021

[22] Asner G. Biophysical and biochemical sources of variability in canopy reflectance[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 1998, 64(3): 234−253. doi: 10.1016/S0034-4257(98)00014-5

[23] Clark M, Roberts D, Clark B. Hyperspectral discrimination of tropical rain forest tree species at leaf to crown scales[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2005, 96(3−4): 375−398. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2005.03.009

[24] Leckie D, Tinis S, Nelson T, et al. Issues in species classification of trees in old growth conifer stands[J]. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing, 2005, 31(2): 175−190. doi: 10.5589/m05-004

[25] 马鸿伟, 刘海, 姚顺彬, 等. 基于林业遥感的树种分类应用分析与展望[J]. 林业资源管理, 2020(3):118−121. Ma H W, Liu H, Yao S B, et al. Application and prospect of tree species classification based on forest remote sensing[J]. Forestry Resource Management, 2020(3): 118−121.

[26] Cao J, Leng W, Liu K, et al. Object-based mangrove species classification using unmanned aerial vehicle hyperspectral images and digital surface models[J/OL]. Remote Sensing, 2018, 10(2): 89 [2021−01−16]. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10010089.

[27] Franklin S, Hall R, Moskal L, et al. Incorporating texture into classification of forest species composition from airborne multispectral images[J]. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2000, 21(1): 61−79. doi: 10.1080/014311600210993

[28] Sayn-Wittgenstein L. Recognition of tree species on aerial photographs[J/OL]. Forest Management Institute Information Report, 1978, FMR-X-118 [2021−01−19]. https://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/pubwarehouse/pdfs/29443.pdf.

[29] Mallinis G, Koutsias N, Tsakiri-Strati M, et al. Object-based classification using Quickbird imagery for delineating forest vegetation polygons in a Mediterranean test site[J]. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry & Remote Sensing, 2008, 63(2): 237−250.

[30] Chuine I, Beaubien E. Phenology is a major determinant of tree species range[J]. Ecology Letters, 2001, 4: 500−510. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00261.x

[31] Gärtner P, Förster M, Kleinschmit B. The benefit of synthetically generated RapidEye and Landsat 8 data fusion time series for riparian forest disturbance monitoring[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2016, 177: 237−247. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2016.01.028

[32] Signoroni A, Savardi M, Baronio A, et al. Deep learning meets hyperspectral image analysis: a multidisciplinary review[J/OL]. Journal of Imaging, 2019, 5(5): 52 [2021−02−13]. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging5050052.

[33] 徐岩, 张聪伶, 降瑞娇, 等. 无人机高光谱影像与冠层树种多样性监测[J]. 生物多样性, 2021, 29(5):647−660. doi: 10.17520/biods.2021013 Xu Y, Zhang C L, Xiang R J, et al. UAV-based hyperspectral images and monitoring of canopy tree diversity[J]. Biodiversity Science, 2021, 29(5): 647−660. doi: 10.17520/biods.2021013

[34] Asner G, Knapp D, Kennedy-Bowdoin T, et al. Invasive species detection in Hawaiian rainforests using airborne imaging spectroscopy and LiDAR[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2008, 112(5): 1942−1955. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2007.11.016

[35] Riaño D, Chuvieco E, Condés S. Generation of crown bulk density for Pinus sylvestris L. from lidar[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2004, 92: 345−352. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2003.12.014

[36] Coops N, Hilker T, Wulder M, et al. Estimating canopy structure of douglas-fir forest stands from discrete-return LiDAR[J]. Trees, 2007, 21: 295−310. doi: 10.1007/s00468-006-0119-6

[37] Suratno A, Seielstad C, Queen L. Tree species identification in mixed coniferous forest using airborne laser scanning[J]. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry & Remote Sensing, 2009, 64(6): 683−693.

[38] Korpela I, Orka H, Hyyppae J, et al. Range and AGC normalization in airborne discrete-return LiDAR intensity data for forest canopies[J]. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry & Remote Sensing, 2010, 65(4): 369−379.

[39] Kim S, McGaughey R, Andersen H, et al. Tree species differentiation using intensity data derived from leaf-on and leaf-off airborne laser scanner data[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2009, 113(8): 1575−1586. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2009.03.017

[40] 黄华国. 激光雷达技术在林业科学研究中的进展分析[J]. 北京林业大学学报, 2013, 35(3):134−143. Huang H G. Progress analysis of LiDAR research on forestry science studies[J]. Journal of Beijing Forestry University, 2013, 35(3): 134−143.

[41] 郭庆华, 刘瑾, 李玉美, 等. 生物多样性近地面遥感监测: 应用现状与前景展望[J]. 生物多样性, 2016, 24(11):1249−1266. doi: 10.17520/biods.2016059 Guo Q H, Liu J, Li Y M, et al. A near-surface remote sensing platform for biodiversity monitoring: perspectives and prospects[J]. Biodiversity Science, 2016, 24(11): 1249−1266. doi: 10.17520/biods.2016059

[42] Michez A, Piegay H, Lisein J, et al. Classification of riparian forest species and health condition using multi-temporal and hyperspatial imagery from unmanned aerial system[J/OL]. Environmental Monitoring & Assessment, 2016, 188: 146 [2021−01−19]. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10661-015-4996-2.

[43] Lu D, Weng Q. A survey of image classification methods and techniques for improving classification performance[J]. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2007, 28: 823−870. doi: 10.1080/01431160600746456

[44] Cheng J, Bo Y, Zhu Y, et al. A novel method for assessing the segmentation quality of high-spatial resolution remote-sensing images[J]. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2014, 35: 3816−3839. doi: 10.1080/01431161.2014.919678

[45] Aguirre-Gutiérrez J, Seijmonsbergen A, Duivenvoorden J. Optimizing land cover classification accuracy for change detection, a combined pixel-based and object-based approach in a mountainous area in Mexico[J]. Applied Geography, 2012, 34: 29−37. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.10.010

[46] Larsen M, Eriksson M, Descombes X, et al. Comparison of six individual tree crown detection algorithms evaluated under varying forest conditions[J]. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2011, 32(20): 5827−5852. doi: 10.1080/01431161.2010.507790

[47] 肖风劲, 欧阳华, 孙江华, 等. 森林生态系统健康评价指标与方法[J]. 林业资源管理, 2004(1):27−30. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-6622.2004.01.007 Xiao F J, Ouyang H, Sun J H, et al. Forest ecosystem health assessment indicators and methods[J]. Forest Resources Management, 2004(1): 27−30. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-6622.2004.01.007

[48] Schlemmer M, Gitelson A, Schepers J, et al. Remote estimation of nitrogen and chlorophyll contents in maize at leaf and canopy levels[J]. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2017, 25: 47−54.

[49] Inoue Y, Sakaiya E, Zhu Y, et al. Diagnostic mapping of canopy nitrogen content in rice based on hyperspectral measurements[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2012, 126: 210−221. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2012.08.026

[50] Xie Q, Huang W, Liang D, et al. Leaf area index estimation using vegetation indices derived from airborne hyperspectral images in winter wheat[J]. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2014, 7(8): 3586−3594. doi: 10.1109/JSTARS.2014.2342291

[51] 黄华国. 林业定量遥感研究进展和展望[J]. 北京林业大学学报, 2019, 41(12):1−14. doi: 10.12171/j.1000-1522.20190326 Huang H G. Progress and prospect of quantitative remote sensing in forestry[J]. Journal of Beijing Forestry University, 2019, 41(12): 1−14. doi: 10.12171/j.1000-1522.20190326

[52] 黄华国. 三维遥感机理模型RAPID原理及其应用[J]. 遥感技术与应用, 2019, 34(5):901−913. Huang H G. Principles and applications of the three-dimensional remote sensing mechanism model RAPID[J]. Remote Sensing Technology and Application, 2019, 34(5): 901−913.

[53] Paul J. Remote sensing of foliar chemistry[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 1989, 30(3): 271−278. doi: 10.1016/0034-4257(89)90069-2

[54] Daughtry C, Walthall C, Kim M, et al. Estimating corn leaf chlorophyll concentration from leaf and canopy reflectance[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2000, 74: 229−239. doi: 10.1016/S0034-4257(00)00113-9

[55] Datt B. Remote sensing of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, chlorophyll a+b, and total carotenoid content in eucalyptus leaves[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 1998, 66: 111−121. doi: 10.1016/S0034-4257(98)00046-7

[56] Asner G, Martin R. Airborne spectranomics: mapping canopy chemical and taxonomic diversity in tropical forests[J]. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2009, 7: 269−276. doi: 10.1890/070152

[57] Ustin S, Gitelson A, Jacquemoud S, et al. Retrieval of foliar information about plant pigment systems from high resolution spectroscopy[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2009, 113: 67−77. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2008.10.019

[58] Malenovský Z, Homolová L, Zurita-Milla R, et al. Retrieval of spruce leaf chlorophyll content from airborne image data using continuum removal and radiative transfer[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2013, 131: 85−102. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2012.12.015

[59] McManus K, Asner G, Martin R, et al. Phylogenetic structure of foliar spectral traits in tropical forest canopies[J/OL]. Remote Sensing, 2016, 8(3): 196 [2021−01−18]. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8030196.

[60] Serrano L, Penuelas J, Ustin S. Remote sensing of nitrogen and lignin in Mediterranean vegetation from AVIRIS data: decomposing biochemical from structural signals[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2002, 81: 355−364. doi: 10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00011-1

[61] Thenkabail P, Lyon J, Huete A. Hyperspectral remote sensing of vegetation[M]. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2016.

[62] Assal T, Anderson P, Sibold J. Spatial and temporal trends of drought effects in a heterogeneous semi-arid forest ecosystem[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 2016, 365: 137−151. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2016.01.017

[63] Klosterman S, Hufkens K, Gray J, et al. Gray J, et al. Evaluating remote sensing of deciduous forest phenology at multiple spatial scales using PhenoCam imagery[J]. Biogeosciences, 2014, 11: 4305−4320. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-4305-2014

[64] van Wittenberghe S, Verrelst J, Rivera J, et al. Gaussian processes retrieval of leaf parameters from a multi-species reflectance, absorbance and fluorescence dataset[J]. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B-Biology, 2014, 134: 37−48. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.03.010

[65] Asner G, Knapp D, Anderson C, et al. Large-scale climatic and geophysical controls on the leaf economics spectrum[J]. PNAS, 2016, 113: 4043−4051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604863113

[66] Schlerf M, Atzberger C, Hill J, et al. Retrieval of chlorophyll and nitrogen in Norway spruce (Picea abies, L. Karst.) using imaging spectroscopy[J]. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2010, 12: 17−26. doi: 10.1016/j.jag.2009.08.006

[67] 章钊颖, 王松寒, 邱博, 等. 日光诱导叶绿素荧光遥感反演及碳循环应用进展[J]. 遥感学报, 2019, 23(1):37−52. Zhang Z Y, Wang S H, Qiu B, et al. Remote sensing retrieval of sunlight induced chlorophyll fluorescence and application of carbon cycle[J]. Acta Remote Sensing, 2019, 23(1): 37−52.

[68] Potter C, Randerson J, Field C, et al. Terrestrial ecosystem production-A process model-based on global satellite and surface data[J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 1993, 7: 811−841. doi: 10.1029/93GB02725

[69] Li X, Xiao J, He B, et al. Chlorophyll fluorescence observed by OCO-2 is strongly related to gross primary productivity estimated from flux towers in temperate forests[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2018, 204: 659−671. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2017.09.034

[70] 郭庆华, 胡天宇, 马勤, 等. 新一代遥感技术助力生态系统生态学研究[J]. 植物生态学报, 2020, 44(4):418−435. doi: 10.17521/cjpe.2019.0206 Guo Q H, Hu T Y, Ma Q, et al. Advances for the new remote sensing technology in ecosystem ecology research[J]. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 2020, 44(4): 418−435. doi: 10.17521/cjpe.2019.0206

[71] Frydenvang J, Maarschalkerweerd M, Carstensen A, et al. Sensitive detection of phosphorus deficiency in plants using chlorophyll a fluorescence[J]. Plant Physiology, 2015, 169: 353−361. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00823

[72] Sun Y, Frankenberg C, Wood J, et al. OCO-2 advances photosynthesis observation from space via solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence[J]. Science, 2017, 358: 747.

[73] Wolanin A, Rozanov V, Dinter T, et al. Global retrieval of marine and terrestrial chlorophyll fluorescence at its red peak using hyperspectral top of atmosphere radiance measurements: feasibility study and first results[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2015, 166: 243−261. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2015.05.018

[74] Köhler P, Guanter L, Joiner J. A linear method for the retrieval of sun-induced chlorophyll fluorescence from GOME-2 and SCIAMACHY data[J]. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 2015, 8(6): 2589−2608. doi: 10.5194/amt-8-2589-2015

[75] Mcroberts R, Næsset E, Gobakken T. Inference for lidar-assisted estimation of forest growing stock volume[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2013, 128: 268−275. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2012.10.007

[76] Cartus O, Kellndorfer J, Rombach M. Mapping canopy height and growing stock volume using airborne lidar, ALOS PALSAR and Landsat ETM+[J]. Remote Sensing, 2012, 4: 3320−3345. doi: 10.3390/rs4113320

[77] 李增元, 赵磊, 李堃, 等. 合成孔径雷达森林资源监测技术研究综述[J]. 南京信息工程大学学报, 2020, 12(2):150−158. Li Z Y, Zhao L, Li K, et al. A survey of developments on forest resources monitoring technology of synthetic aperture radar[J]. Journal of Nanjing University of Information Technology, 2020, 12(2): 150−158.

[78] 李亚东, 冯仲科, 明海军, 等. 无人机航测技术在森林蓄积量估测中的应用[J]. 测绘通报, 2017(4):63−66. Li Y D, Feng Z K, Ming H J, et al. Application of UAV aerial survey technology in forest volume estimation[J]. Surveying and Mapping Bulletin, 2017(4): 63−66.

[79] 黄麟, 张晓丽, 石韧. 森林病虫害遥感监测技术研究的现状与问题[J]. 遥感信息, 2006(2):71−75. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3177.2006.02.020 Huang L, Zhang X L, Shi R. Current status and problems in monitoring forest damage caused by diseases and insects based on remote sensing[J]. Remote Sensing Information, 2006(2): 71−75. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3177.2006.02.020

[80] 王蕾, 骆有庆, 张晓丽, 等. 遥感技术在森林病虫害监测中的应用研究进展[J]. 世界林业研究, 2008, 21(5):37−43. Wang L, Luo Y Q, Zhang X L, et al. Application development of remote sensing technology in the assessment of forest pest disaster[J]. World Forestry Research, 2008, 21(5): 37−43.

[81] Stone C, Mohammed C. Application of remote sensing technologies for assessing planted forests damaged by insect pests and fungal pathogens: a review[J]. Current Forestry Reports, 2017, 3(2): 1−18.

[82] Hall R J, van der Sanden J J, Freeburn J T, et al. Remote sensing of natural disturbance caused by insect defoliation and dieback: a review[R]. Edmonton: Natural Resources Canada, 2016.

[83] Coops N, Johnson M, Wulder M, et al. Assessment of QuickBird high spatial resolution imagery to detect red attack damage due to mountain pine beetle infestation[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2006, 103(1): 67−80. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2006.03.012

[84] Bright B, Hudak A, McGaughey R, et al. Predicting live and dead tree basal area of bark beetle affected forests from discrete-return lidar[J]. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing, 2013, 39: 99−111. doi: 10.5589/m13-027

[85] Carter G, Knapp A. Leaf optical properties in higher plants: linking spectral characteristics to stress and chlorophyll concentration[J]. American Journal of Botany, 2001, 88: 677−684. doi: 10.2307/2657068

[86] Ustin S, Roberts D, Gamon J, et al. Using imaging spectroscopy to study ecosystem processes and properties[J]. Bioscience, 2004, 54: 523−534. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0523:UISTSE]2.0.CO;2

[87] Niemann K, Quinn G, Stephen R, et al. Hyperspectral remote sensing of mountain pine beetle with an emphasis on previsual assessment[J]. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing, 2015, 41(3): 191−202. doi: 10.1080/07038992.2015.1065707

[88] Hernández-Clemente R, Hornero A, Mottus M, et al. Early diagnosis of vegetation health from high-resolution hyperspectral and thermal imagery: lessons learned from empirical relationships and radiative transfer modelling[J]. Current Forestry Reports, 2019, 5: 169−183. doi: 10.1007/s40725-019-00096-1

[89] Abdullah H, Darvishzadeh R, Skidmore A, et al. European spruce bark beetle (Ips typographus L.) green attack affects foliar reflectance and biochemical properties[J]. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation & Geoinformation, 2018, 64: 199−209.

[90] Peterson D, Aber J, Matson P, et al. Remote sensing of forest canopy and leaf biochemical contents[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 1988, 24: 85−108. doi: 10.1016/0034-4257(88)90007-7

[91] 徐华潮, 骆有庆, 张廷廷, 等. 松材线虫自然侵染后松树不同感病阶段针叶光谱特征变化[J]. 光谱学与光谱分析, 2011, 31(5):1352−1356. doi: 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2011)05-1352-05 Xu H C, Luo Y Q, Zhang T T, et al. Changes of reflectance spectra of pine needles in different stage after being infected by pine wood nematode[J]. Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis, 2011, 31(5): 1352−1356. doi: 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2011)05-1352-05

[92] Liu Y J, Zhan Z Y, Ren L L, et al. Hyperspectral evidence of early-stage pine shoot beetle attack in Yunnan pine[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 2021, 497: 1118−1127.

[93] Yu L, Zhan Z, Ren L, et al. Evaluating the potential of worldview-3 data to classify different shoot damage ratios of Pinus yunnanensis[J/OL]. Forests, 2020, 11: 417 [2021−01−14]. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11040417.

[94] Zhan Z, Yu L, Ren L, et al. Combining GF-2 and Sentinel-2 images to detect tree mortality caused by red turpentine beetle during the early outbreak stage in north China[J]. Forests, 2020, 11(2): 172. doi: 10.3390/f11020172

[95] Senf C, Pflugmacher D, Hostert P, et al. Using Landsat time series for characterizing forest disturbance dynamics in the coupled human and natural systems of Central Europe[J]. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 2017, 130: 453−463. doi: 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2017.07.004

[96] Yu L, Huang J, Zong S, et al. Detecting shoot beetle damage on Yunnan pine using Landsat time-series data[J/OL]. Forests, 2018, 9: 39 [2021−01−19]. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9010039.

[97] Gašparović M, Jurjević L. Gimbal influence on the stability of exterior orientation parameters of UAV acquired images[J/OL]. Sensors, 2017, 17(2): 401 [2021−01−15]. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17020401.

[98] Näsi R, Honkavaara E, Paivi L, et al. Using UAV-based photogrammetry and hyperspectral imaging for mapping bark beetle damage at tree-level[J]. Remote Sensing, 2015, 7: 15467−15493. doi: 10.3390/rs71115467

[99] Yu R, Luo Y Q, Zhou Q, et al. A machine learning algorithm to detect pine wilt disease using UAV-based hyperspectral imagery and LiDAR data at the tree level[J/OL]. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2021, 101(1): 102363 [2021−01−21]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2021.102363.

[100] 鲁芮伶, 杜莹, 晏黎明, 等. 森林树木死亡的判定方法及其应用综述[J]. 科学通报, 2019, 64(23):2395−2409. Lu R L, Du Y, Yan L M, et al. A review of forest tree death determination methods and their application[J]. Scientific Bulletin, 2019, 64(23): 2395−2409.

[101] Parker J, Patton R. Effects of drought and defoliation on some metabolites in roots of black oak seedlings[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 1975, 5: 457−463. doi: 10.1139/x75-063

[102] Hartmann H, Ziegler W, Trumbore S. Lethal drought leads to reduction in nonstructural carbohydrates in Norway spruce tree roots but not in the canopy[J]. Functional Ecology, 2013, 27: 413−427. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12046

[103] Adams H, Zeppel M, Anderegg W, et al. A multi-species synthesis of physiological mechanisms in drought-induced tree mortality[J]. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 2017, 1: 1285−1291. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0248-x

[104] 周国逸, 李琳, 吴安驰. 气候变暖下干旱对森林生态系统的影响[J]. 南京信息工程大学学报(自然科学版), 2020, 12(1):81−88. Zhou G Y, Li L, Wu A C. Effect of drought on forest ecosystem under warming climate[J]. Journal of Nanjing University of Information Technology (Nature Science Edition), 2020, 12(1): 81−88.

[105] Bowman W. The relationship between leaf water status, gas exchange, and spectral reflectance in cotton leaves[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 1989, 30(3): 249−255. doi: 10.1016/0034-4257(89)90066-7

[106] 郝增超, 侯爱中, 张璇, 等. 干旱监测与预报研究进展与展望[J]. 水利水电技术, 2020, 51(11):30−40. Hao Z C, Hou A Z, Zhang X, et al. Study progresses and prospects of drought monitoring and prediction[J]. Water Conservancy and Hydropower Technology, 2020, 51(11): 30−40.

[107] 周磊, 武建军, 张洁. 以遥感为基础的干旱监测方法研究进展[J]. 地理科学, 2015, 35(5):630−636. Zhou L, Wu J J, Zhang J. Remote sensing-based drought monitoring approach and research progress[J]. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 2015, 35(5): 630−636.

[108] Li X, Xiao J, He B. Higher absorbed solar radiation partly offset the negative effects of water stress on the photosynthesis of Amazon forests during the 2015 drought[J/OL]. Environmental Research Letters, 2018, 13(4): 044005 [2020−10−12]. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aab0b1.

[109] Reddy A, Chaitanya K, Vivekanandan M. Drought-induced responses of photosynthesis and antioxidant metabolism in higher plants[J]. Journal of Plant Physiology, 2004, 161(11): 1189−1202. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.01.013

[110] Lambers H, Chapin F, Chapin F, et al. Plant water relations in plant physiological ecology[M]. New York: Springer, 2008: 163−217.

[111] Breshears D, Cobb N, Rich P, et al. Regional vegetation die-off in response to global change-type drought[J]. PNAS, 2005, 102(42): 15144−15148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505734102

[112] Running S, Nemani R, Heinsch F, et al. A continuous satellite-derived measure of global terrestrial primary production[J]. Bioscience, 2004, 54(6): 547−560. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0547:ACSMOG]2.0.CO;2

[113] Huang C, Asner G, Barger N, et al. Regional aboveground live carbon losses due to drought-induced tree dieback in Pinyon-Juniper ecosystems[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2010, 114(7): 1471−1479. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2010.02.003

[114] Clifford M, Cobb N, Buenemann M. Long-term tree cover dynamics in a Pinyon-Juniper woodland: climate-change-type drought resets successional clock[J]. Ecosystems, 2011, 14(6): 949−962. doi: 10.1007/s10021-011-9458-2

[115] Suárez L, Zarco-Tejada P, Sepulcre-Cantó G, et al. Assessing canopy PRI for water stress detection with diurnal airborne imagery[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2008, 112(2): 560−575. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2007.05.009

[116] 黄华国. 森林病虫害定量遥感模型进展[C]//第一届植被病虫害遥感大会. 北京: 中国科学院空天信息创新研究院, 2020. Huang H G. Advances in quantitative remote sensing models of forest diseases and insect pests[C]//The first congress on remote sensing of plant diseases and insect pests. Beijing: Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2020.

[117] 李树涛, 李聪妤, 康旭东. 多源遥感图像融合发展现状与未来展望[J]. 遥感学报, 2021, 25(1):148−166. Li S T, Li C Y, Kang X D. Development status and future prospects of multi-source remote sensing image fusion[J]. National Remote Sensing Bulletin, 2021, 25(1): 148−166.

[118] 武士翔. “科技蓝 + 森林绿”助力雄安生态格局: 基于雄安新区植树造林项目的研究[J]. 城市建筑, 2019, 16(26):149−150. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-0232.2019.26.049 Wu S X. “Science and technology blue + forest green” helps Xiong’an ecological pattern based on the afforestation project in Xiong’an new district[J]. Urban Architecture, 2019, 16(26): 149−150. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-0232.2019.26.049

[119] Gorelick N, Hancher M, Dixon M, et al. Google earth engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone[J]. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2017, 202: 18−27. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2017.06.031

-

期刊类型引用(23)

1. 栗世博,赖巧巧,屈峰. 森林“四库”研究的热点、前沿和动态. 林业经济问题. 2025(01): 41-51 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 李子辉,张亚,巴永,陈伟志,董春凤,杨梦娇,文方平. 云南省植被固碳能力与产水、土壤保持服务冷热点识别. 中国环境科学. 2024(02): 1007-1019 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 傅乐乐,苏建兰,张凯迪. 云南省经济林碳汇测算及其产品开发探析. 现代农业研究. 2024(02): 34-39 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 丁琦珂,豆浩,张二山,胡传伟,何静. 郑州市园林绿化树种的含碳率分析. 林草资源研究. 2024(01): 95-101 .  百度学术

百度学术

5. 宋立,顾至欣,郭剑英. “双碳”目标下旅游碳排放影响因素变化规律研究. 生态经济. 2024(05): 132-137+188 .  百度学术

百度学术

6. 钟金发,邓佳露,翁志强,林榅荷. 森林“碳库”经济价值实现机制研究. 林业经济问题. 2024(01): 42-50 .  百度学术

百度学术

7. 张洪宇,程振博. 中国森林碳汇效度动态演进及时空演变格局. 天津农林科技. 2024(03): 37-42 .  百度学术

百度学术

8. 叶军,朱妍妍,陈立勇,张露,邢玮,何冬梅. 泰州市森林碳储量现状及碳汇能力分析. 江苏林业科技. 2024(03): 16-21+57 .  百度学术

百度学术

9. 朱诗柔,牟凤云,黄淇,沈祺林. 2000—2030年多级流域尺度下重庆市林地景观格局碳储量变化. 水土保持通报. 2024(03): 356-366 .  百度学术

百度学术

10. 王彩玲. 定西市林业碳汇高质量发展存在的问题及对策. 甘肃科技纵横. 2024(08): 48-54 .  百度学术

百度学术

11. 康嘉怡,何正斌,刘书言,伊松林. 实木家具制造过程能耗及碳排放分析. 家具. 2024(06): 9-14 .  百度学术

百度学术

12. 曲学斌,王雅莹,李丹,赵岳冀,张岚彪. 内蒙古大兴安岭森林固碳能力时空变化及气象因素影响分析. 沙漠与绿洲气象. 2024(06): 117-123 .  百度学术

百度学术

13. 刘蕊婷,马淑娟,张学万,陈飞勇,杜玉凤,徐景涛,王晋. 森林生态系统五大碳库碳储量估算模型及其影响因素研究进展. 林业建设. 2024(06): 11-25 .  百度学术

百度学术

14. 胡勐鸿,李万峰,吕寻. 日本落叶松自由授粉家系选择和无性繁殖利用. 温带林业研究. 2023(01): 7-16 .  百度学术

百度学术

15. 刘艳丽. 森林碳汇计量关键技术应用研究. 林业勘查设计. 2023(02): 86-90 .  百度学术

百度学术

16. 叶家义,付军,陆卫勇,欧军,何斌. 南亚热带13年生大叶栎人工林固碳功能分析. 亚热带农业研究. 2023(01): 38-43 .  百度学术

百度学术

17. 莫少壮,罗星乐,李嘉方,刘凡胜,何斌. 南丹县毛竹人工林生态系统生物量、碳储量及其分配格局. 农业研究与应用. 2023(01): 39-44 .  百度学术

百度学术

18. 肖龙海. 贵州省林业碳汇发展探索与讨论. 现代园艺. 2023(12): 165-167+170 .  百度学术

百度学术

19. 张少博,叶长存,郭帅,吕俊彦,陈烨,颜鹏,李征珍,李鑫. 农林土壤固碳减排技术研究进展及其在茶树栽培中的应用潜力. 中国茶叶. 2023(11): 10-17 .  百度学术

百度学术

20. 张凯迪,苏建兰. 云南省防护林固碳贡献与增汇对策. 林业建设. 2023(06): 37-43 .  百度学术

百度学术

21. 于欢,魏天兴,陈宇轩,沙国良,任康,辛鹏程,郭鑫. 黄土丘陵区典型人工林土壤有机碳储量的分布特征. 北京林业大学学报. 2023(12): 100-107 .  本站查看

本站查看

22. 蔡爽. 森林培育对生态环境建设的影响研究. 造纸装备及材料. 2022(11): 156-158 .  百度学术

百度学术

23. 周亚敏. 全球发展倡议下的中拉气候合作:基础、机遇与挑战. 拉丁美洲研究. 2022(06): 85-99+156-157 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(18)

下载:

下载: