Histological characteristics and related gene expression analysis of ovule abortion in Camellia oleifera

-

摘要:目的 油茶胚珠败育现象严重,只有少数胚珠能发育为成熟种子,但其败育机制尚不清楚。本研究对油茶胚珠败育时期、组织结构变化和败育原因展开探究,旨在明确油茶胚珠的败育过程,为提高油茶产量提供一定的理论基础和实践意义。方法 本研究以‘华硕’品种果实为试验材料,在体视显微镜下观察油茶果实内胚珠的形态,统计败育率,采用荧光素二乙酸酯(FDA)染色观察败育胚珠失去活性的时间;通过石蜡切片和显微镜观察明确可育胚珠和败育胚珠的组织结构变化,通过碘−碘化钾染色和PAS反应标记可育胚珠与败育胚珠中淀粉粒的分布。利用CFDA荧光示踪和激光共聚焦成像技术揭示同化物在可育胚珠与败育胚珠中的运输路径,通过实时荧光定量PCR试验分析与糖和能量代谢、活性氧代谢、细胞凋亡等过程相关的基因在可育胚珠与败育胚珠中的表达情况。结果 (1)体式显微镜的观察结果显示26 WAA(花后周数)后油茶可育胚珠与败育胚珠的大小产生差异;FDA标记结果说明,败育胚珠在果实发育过程中逐步失去活性。(2)37 WAA时,胚珠败育率达到64.08%。(3)显微观察显示:可育胚珠的胚和胚乳均正常发育,内外珠被结合紧密;败育胚珠无胚乳细胞,内珠被与外珠被之间的空隙较大;可育胚珠的胚柄和胚乳中均有淀粉粒存在,败育胚珠仅在萎缩的内珠被上观察到少量淀粉粒。可育胚珠的内珠被上无胼胝质沉积,败育胚珠的内珠被上可见胼胝质沉积。(4)CFDA荧光示踪结果发现,败育胚珠与可育胚珠的同化物运输方式存在差异。(5)与糖和能量代谢、活性氧代谢、细胞凋亡等过程相关基因在败育胚珠和可育胚珠中存在差异性表达。结论 败育胚珠的结构异常,胚珠内缺乏淀粉的积累,内珠被上有胼胝质沉积,同化物的运输方式与可育胚珠不同,参与胚珠物质和能量代谢、抗氧化作用和细胞凋亡等过程的基因的差异表达可能与油茶胚珠的败育有关。Abstract:Objective The ovule abortion of Camellia oleifera is serious. Only a few ovules could develop into mature seeds, but its abortion mechanism is not clear. The research investigated abortion period, microstructure changes and abortion reasons of ovules to clarify the abortion process and to provide certain theoretical basis and practical significance for increasing the yield of Camellia oleifera.Method The fruits of C. oleifera cv. ‘Huashuo’ were chosen as the experimental material. The ovule morphology in Camellia oleifera fruit was observed under stereomicroscope. We counted the proportion of abortive ovules. The stage of losing activity of abortive ovules was observed by FDA staining technique and stereomicroscope. The histological changes of fertile and abortive ovules were clarified by paraffin technique and microscopic observation, and the starch grain distribution in fertile and abortive ovules was marked by K-KI2 staining and PAS reaction. The CFDA fluorescence tracing experiment and laser confocal microscopy were used to reveal assimilate transport pathways in fertile and abortive ovules. The qRT-PCR was used to analyze the expression of genes related to sugar and energy metabolism, reactive oxygen species metabolism, and apoptosis processes in fertile and abortive ovules.Result (1) The stereomicroscope observation showed that the size of fertile and abortive ovules differed after 26 WAA (weeks after anthesis). The results of FDA staining indicated that the abortive ovules gradually lost their activity during fruit development. (2) At 37 WAA, the proportion of abortive ovules reached 64.08%. (3) Microscopic observation showed that the embryo and endosperm of fertile ovules developed normally, and the inner and outer integuments were tightly united; the abortive ovules had no endosperm cells, and the space between the inner and outer integument was wild. Starch grains were observed in both the suspensor and endosperm of fertile ovules, and only a few starch grains were observed on the shrunken inner integuments of abortive ovules. (4) CFDA fluorescence tracing results revealed differences in assimilate transport modes between fertile and abortive ovules. There was no callose deposition on the inner integument of fertile ovules, while callose deposition can be seen on the inner integument of abortive ovules. (5) Genes related to sugar and energy metabolism, reactive oxygen species metabolism, and apoptosis processes were differentially expressed in fertile and abortive ovules.Conclusion The abortive ovules have abnormal structure and lack starch accumulation. There are some callose depositions on inner integument. There are differences in the transport modes of assimilates between abortive ovules and fertile ovules. Different expressions of genes about material and energy metabolism, antioxidant action and apoptosis processed in the ovules might be related to the abortion of Camellia oleifera ovules.

-

Keywords:

- Camellia oleifera /

- ovule /

- abortive /

- histological characteristics

-

森林是一个国家的重要资源,在防治水土流失、改善生态环境方面发挥着重要作用,具有良好的生态效益和社会效益[1]。但是,一直以来森林不断遭受着病虫害的侵扰,大量的农药被用来防治病虫害的发生。在防治的同时,大量农药喷洒在林地上,部分农药残留渗入地下,经由河流汇入湖泊,不可避免对环境水体造成一定污染[2]。

拟除虫菊酯是一类广泛使用的杀虫剂,是衍生自菊花和植物花的除虫菊酯的合成衍生物[3]。它们通常被大量用于林业、农业等领域[4]。据报道,在中国,每年消耗3 700多吨拟除虫菊酯类农药,用于害虫防治[5]。大量拟除虫菊酯的使用会导致生态环境的污染,同时,如果人体长期过量接触拟除虫菊酯,会产生严重的健康问题,引发包括恶心、呕吐、呼吸抑制、精神变化、急性肾损伤等疾病症状[6]。因此,有必要对环境水体中的拟除虫菊酯进行检测。

由于样品的复杂性和低浓度性,需要进行样品预处理才能够进行检测。传统的萃取方法有液液萃取(LLE)[7]、索氏提取(Soxhlet extraction)[8]、固相萃取(SPE)[9]等。液液萃取易于使用,无需使用复杂的仪器执行。然而,高毒性有机溶剂的大量消耗和提取分析物的低选择性限制了液液萃取的使用。与液液萃取相比,固相萃取消耗较少量的有机溶剂,但相对昂贵且耗时[10]。因此,近年来的样本前处理技术不断向绿色化、微型化和简便化方向发展。

分散液液微萃取(DLLME)是常用的农药残留检测方法,具有操作简单、快速、成本低等优点。该方法由Rezaee等[11]于2006年提出来,主要包括两个步骤:萃取剂分散和回收。传统分散液液微萃取需要采用有机分散剂进行分散,既消耗了有机溶剂,又降低了分析物的分配系数。近年来不需要有机分散剂的辅助分散方法逐渐被开发出来,丰富了分散液液微萃取技术。具体分散技术包括手动摇晃[12]、涡旋[13]、超声[14]、微波[15]等。其中,手动摇晃因为重现性差而逐渐被其他方式代替,而其他几种方式都需要使用仪器进行操作,难以现场进行。2014年,Lasade-Aragones等人首次引入了泡腾辅助分散液液微萃取(EA-DLLME),它是通过酸和碳酸盐或碳酸氢盐发生泡腾反应,产生二氧化碳将萃取剂分散[16]。因其不受超声、涡旋等仪器限制,具有现场处理的可能,且具有环境副作用小的优点,越来越受到欢迎[17]。

最近,可转换亲水性溶剂(SHS)已被用作液相微萃取中的萃取剂[18]。中链脂肪酸被认为是可转换亲水性溶剂[19],其机理是通过调节pH值实现可溶和不溶之间的转化[20]。而且,中链脂肪酸的钠盐和泡腾片都是可溶性固体粉末,泡腾反应能够促进可转换亲水性溶剂的分散和溶解,同时,泡腾片中过量的酸可以促使萃取剂从可溶性转变为不溶性,从而完成萃取过程。因此,将可转换亲水性溶剂与泡腾片结合非常利于微萃取过程的完成[17]。

萃取剂相的分离是液相微萃取技术的重要步骤,离心是常用的相分离方法,但是离心步骤涉及到离心机的使用,而大型仪器的存在使得前处理过程难以在现场操作[21]。基于此问题,研究者开发出多种现场处理方法。磁性纳米粒子(MNPs)分散在溶液中吸附萃取剂,借助于磁铁吸附作用实现汇聚,最终洗脱得到萃取剂,整个过程不需要使用大型仪器,方便现场操作[16]。另外,利用低密度溶剂会漂浮在溶液上层的性质,刘学科等使用1-十一烷醇作为萃取剂,采用移液管吸收上层液体的方法以实现现场处理[22]。最近,采用过滤方式进行相分离的方法也可以很好地在现场进行[23]。本课题组已制作具有良好亲油疏水性的过滤柱,采用过滤方式实现萃取剂的回收[24]。目前还没有研究采用泡腾片分散和过滤分离相结合的方法,来进行样品的现场前处理。

因此,在现场处理的基础上,本研究开发了一种基于可转换亲水性溶剂的泡腾片辅助分散液液微萃取结合气相色谱法,测定环境水中的拟除虫菊酯类农药。该方法按照一定配方压制泡腾片,用于萃取剂的分散,采用过滤方式进行相分离,成功完成了前处理步骤和气相色谱仪检测。整个提取过程不依赖任何特殊仪器,这使得该方法得以成功地应用于现场处理。目前,该方法已成功应用于北京市环境水的检测。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 试剂和材料

5种拟除虫菊酯类农药标准品(联苯菊酯、氟氰菊酯、氯氰菊酯、氰戊菊酯、溴氰菊酯)购自坛墨质量检测技术有限公司(江苏,中国),纯度均 > 98%。己酸钠(99%)、壬酸钠(98%)购自百灵威公司(北京,中国)。柠檬酸、磷酸二氢钠、碳酸氢钠、碳酸钠均购自麦克林公司(上海,中国)。SPE色谱柱购自安捷伦科技公司(美国)。聚丙烯吸油棉和聚丙烯无纺布购自苏州伊路发环保技术有限公司(江苏,中国)。

1.2 仪器与设备

安捷伦7890B型气相色谱仪(美国安捷伦科技公司,美国),配备电子捕获检测器;DB-5 MS型毛细管柱(30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 µm);手动液压压片机购自鹤壁立信仪器有限公司(河南,中国);Milli-Q超纯水系统(Millipore,美国);万分之一天平;微量进样针;一次性注射器。

1.3 标准储备溶液和实际样品

使用色谱级乙腈,分别配制5种拟除虫菊酯标准品的标准溶液(2 000 μg/mL),并在4 ℃的冰箱中储存。将5种标准溶液等体积混合配制混合标准溶液。将混合标准溶液稀释至不同浓度,得到工作标准溶液。自来水、水库水和河水均采集于中国北京。水样收集在玻璃瓶中,避光储存。

1.4 泡腾片压制

使用万分天平称量0.499 2 g柠檬酸、0.405 6 g磷酸二氢钠、0.218 4 g碳酸氢钠和0.180 0 g己酸钠,加入到研钵中,手动研磨直至获得均匀细致的粉末。然后,将粉末放入直径12 mm模具中,使用手动液压压片机在1 MPa的压力下压制成泡腾片,取出泡腾片,干燥储存或直接使用。

1.5 自制过滤柱制备

自制过滤柱制备过程如图1所示,它由3部分组成:SPE外壳、吸油棉填料和适配器。先将1 mL SPE色谱柱裁剪至合适的高度,底部加入一个垫片;然后将吸油棉切成长条状,卷成圆柱形,填充到SPE柱中,起到过滤作用,在上部再压上一个垫片;最后将适配器插入色谱柱上方,获得自制过滤柱。

1.6 样品前处理过程

取10 mL水样品注入20 mL注射器中,注射器下端接转接头,加入已制备的泡腾片,待泡腾片完全反应、注射器中无气泡产生时,打开转接头,使用自制过滤柱过滤注射器中溶液,再使用50 mL注射器吹干自制过滤柱上残留水滴,最后使用200 μL乙腈洗脱得到分析物,进行气相色谱电子捕获检测器(GC-ECD)检测。

2. 结果与讨论

2.1 方法优化

2.1.1 萃取剂类型

萃取剂的选择朝着越来越绿色、环保、低毒等的方向发展,因此,本研究选择了两种可转换性溶剂(己酸钠和壬酸钠)进行优化,其他条件如下:脂肪酸盐的量为0.16 g,泡腾片成分包括0.499 2 g柠檬酸、0.405 6 g 磷酸二氢钠和0.218 4 g 碳酸氢钠,无盐,自制过滤柱(填料吸油棉,高度为2 cm,密度为60 mg/cm),洗脱剂乙腈200 μL。结果如图2所示,对样本进行显著性检验,P < 0.01,两组间差异极显著,而己酸钠具有更高的响应值,因此,己酸钠萃取效果更佳,用于后续的优化实验。

2.1.2 萃取剂用量

泡腾片中己酸钠的用量需要进行优化,以获得最佳的条件。在实验中,检测了不同用量己酸钠(0.16、0.18、0.20、0.22 g)对峰面积的影响,其他条件同上。如图3所示,不同萃取剂用量差异显著(P < 0.01),当萃取剂为0.16 g时,峰面积最大,随着萃取剂用量的增加,峰面积逐渐减小。因此,最终选择0.16 g己酸钠进行后续优化实验。

2.1.3 泡腾片的类型

泡腾反应对萃取剂的分散和萃取具有重要影响。不同类型的泡腾片将发生不同时长和强度的泡腾反应,从而影响最终的萃取效果。在实验中,我们选择了4种物质(柠檬酸,磷酸二氢钠,碳酸氢钠和碳酸钠)进行测定。4种方案如表1所示。泡腾片中的酸不仅与碳酸盐发生泡腾反应,而且与萃取剂反应,使萃取剂从可溶状态转变为不溶状态,完成萃取。基于该过程对酸的双重要求,具有较强酸性的柠檬酸成为最佳选择。实验中同时发现,柠檬酸酸性较强,反应迅速,反应时间过短,导致萃取剂分散不充分,萃取效果受到影响,所以,加入弱酸磷酸二氢钠作为调节剂,延缓反应的速度,延长反应的时间,使萃取剂在分散、转化和萃取过程更为充分。根据图4所示,P < 0.01表明差异极显著,综合A、B、C、D四个方案显示,方案A的反应速度和反应强度更为优化,萃取效果更佳。因此,泡腾片制备选择方案A(柠檬酸 + 磷酸二氢钠 + 碳酸氢钠 + 己酸钠)。

表 1 不同泡腾片成分方案Table 1. Scheme of different effervescent tablets编号 No. 方案 Scheme 反应时间 Reaction time/s A 柠檬酸 + 磷酸二氢钠 + 碳酸氢钠 + 己酸钠

Citric acid + sodium dihydrogen phosphate + sodium bicarbonate + sodium hexanoate60 B 柠檬酸 + 磷酸二氢钠 + 碳酸钠 + 己酸钠

Citric acid + sodium dihydrogen phosphate + sodium carbonate + sodium hexanoate80 C 柠檬酸 + 碳酸氢钠 + 己酸钠 Citric acid + sodium bicarbonate + sodium hexanoate 15 D 柠檬酸 + 碳酸钠 + 己酸钠 Citric acid + sodium carbonate + sodium hexanoate 30 2.1.4 酸碱比

萃取剂己酸钠很容易受到pH值的影响,因此有必要对泡腾片的酸碱比进行优化。根据酸碱电离理论,柠檬酸可产生3个H+,磷酸二氢钠可产生1个H+,碳酸氢钠和己酸钠可产生一个OH−。因此,根据不同的酸碱比(6∶2∶1∶1,8∶2∶1∶1,10∶2∶1∶1)进行优化。结果如图5所示,进行显著性分析,P > 0.05,差异性不显著,表明pH的变化能够对峰面积产生影响,但是目前范围变化影响不大。据图可知,在柠檬酸∶磷酸二氢钠∶碳酸氢钠∶己酸钠的比例为8∶2∶1∶1的情况下,可获得最佳峰面积。因此,泡腾片质量为0.499 2 g柠檬酸,0.405 6 g磷酸二氢钠、0.218 4 g碳酸氢钠、0.18 g己酸钠,进行下一步实验。

2.1.5 盐效应的影响

通过向水样中添加不同量的盐(0 ~ 10%, w/w)来调节盐的质量分数,从而评估盐效应带来的影响。如图6所示,随着盐质量分数的增加,不同农药的响应幅度显示出差异,联苯菊酯和氰戊菊酯P < 0.01,差异极显著,受盐效应影响较大,抑制作用明显;而氟氯氰菊酯、氰戊菊酯、溴氰菊酯P > 0.05,差异不显著,变化不大。总体上盐质量分数的增加起到了抑制作用。因此,最终选择零添加进行后续研究。

2.1.6 自制过滤柱填料类型

自制过滤柱是进行相分离的重要设备。而自制过滤柱的填料是影响分离效果的重要因素。吸油棉和无纺布被选作自制过滤柱的填料,二者都是聚丙烯材料,能够在过滤过程中吸附萃取剂,完成相分离,但是在亲脂性和疏水性的性能上存在差异,因此有必要对其进行优化。结果如图7所示,显著性检验P < 0.01,表明不同填料类型差异极显著,吸油棉效果显著高于无纺布。因此,吸油棉用于后续实验。

2.1.7 自制过滤柱填料的高度和密度

自制过滤柱填料的高度和密度会影响过滤性能。如果过滤柱填料过高,则需要消耗更多的洗脱剂,降低响应值;如果过滤柱填料过低,则容易无法完全保留过滤溶液中的萃取剂,影响回收效率,所以,选择合适的高度对于该方法具有重要影响。因此,研究了1.5、2.0和2.5 cm高度对峰面积的影响,结果如图8所示,显著性检验P > 0.05,差异不显著,考虑到在2 cm高度时,除联苯菊酯外,其他几种农药微弱高于其他条件。因此,选择了2.0 cm高度的自制过滤柱进行进一步研究。

如果过滤材料太紧,则会影响过滤速度;如果过滤材料太稀疏,萃取剂将很容易被冲洗掉。所以,有必要对过滤柱的密度进行优化。因此,在2.0 cm的高度条件下,研究了不同密度的填料(40、50、60、70 mg/cm)对峰面积的影响,结果如图9所示,显著性检验显示联苯菊酯、氰戊菊酯和溴氰菊酯P < 0.05,差异显著,峰面积呈现先增后减的趋势,在60 mg/cm处获得最佳效果。因此,最佳密度选择为60 mg/cm。

2.2 方法评价

为了评价所建立方法的性能,评估了包括线性范围、线性方程、相关系数、检测限、定量限、相对标准偏差和富集倍数在内的参数。在优化条件下进行研究,结果如表2所示,在5 ~ 500 μg/L的线性范围内,相关系数均 ≥ 0.999 0,线性关系良好。检出限和定量限分别为0.22 ~ 1.88 μg/L和0.75 ~ 6.25 μg/L。日内标准差和日间标准差分别低于6.1%和5.4%。富集倍数在65 ~ 108范围内。

表 2 5种菊酯的线性方程、相关系数及检出限Table 2. Linear equation, correlation coefficients and detection limits of five pyrethroids化合物

Compounds线性范围

Range of

linearity/

(μg·L−1)线性方程

Linearity

equation相关系数

Correlation

coefficient检出限

Limit of

detection/

(μg·L−1)定量限

Limit of

quantitation/

(μg·L−1)日内标准差

Intra-day

SD/%日间标准差

Inter-day

SD/%富集倍数

Enrichment

factor联苯菊酯 Bifenthrin 5 ~ 500 y = 94.8x − 217.5 0.999 0 0.22 0.75 6.1 0.8 108 氟氯氰菊酯 Cyfluthrin 5 ~ 500 y = 24.916x + 67.895 0.999 4 1.03 3.45 2.2 5.4 71 氯氰菊酯 Cypermethrin 5 ~ 500 y = 13.341x + 42.416 0.999 6 1.65 5.49 3.0 4.6 65 氰戊菊酯 Fenvalerate 5 ~ 500 y = 68.004x + 165.82 0.999 6 0.39 1.29 4.3 2.9 66 溴氰菊酯 Deltamethrin 5 ~ 500 y = 21.184x − 51.306 0.999 9 1.88 6.25 1.9 1.3 93 2.3 实际样品分析

为了进一步验证所开发方法的可靠性和适用性,本研究分析了包括自来水、库水、水在内的3种实际样品。添加质量浓度为0、50、200 μg/L,样品回收率总结于表3,空白样品与加标样品色谱图见于图10。结果显示:所有空白实际水样均未检测到农药残留,表明采样地水质较为纯净。加标样品的回收率为88.2% ~ 113.0%,相对标准偏差在4.5% ~ 11.8%之间,均在可接受范围。因此,该方法可以成功准确地检测环境中水样。

表 3 使用建立的方法对3种实际水样进行分析Table 3. Analytical performance of the proposed method for three real samples化合物

Compounds自来水 Tap water 水库水 Reservoir water 河流水 River water 添加水平

Spiked level/(μg·L−1)回收率

Relative recovery/%标准差

SD/%回收率

Relative recovery/%标准差

SD/%回收率

Relative recovery/%标准差

SD/%联苯菊酯

Bifenthrin50 92.3 8.3 94.5 4.5 105.1 6.8 200 113.0 5.7 97.8 8.1 107.6 10.0 氟氯氰菊酯

Cyfluthrin50 106.2 6.1 104.8 7.3 104.6 7.9 200 109.7 7.4 103.2 8.3 99.5 7.5 氯氰菊酯

Cypermethrin50 98.2 7.5 96.4 7.9 97.5 9.3 200 108.5 5.7 99.1 9.2 100.2 8.9 氰戊菊酯

Fenvalerate50 96.8 6.9 96.5 6.1 104.4 6.4 200 110.8 5.0 93.7 8.6 102.7 8.2 溴氰菊酯

Deltamethrin50 88.2 8.6 88.7 5.2 97.1 8.8 200 101.6 6.0 89.6 10.2 98.8 11.8 2.4 方法比较

为了体现现场分散液液微萃取结合气相色谱法(On-stie DLLME-GC)的优越性,该方法与已报道方法的几个重要参数进行了比较。如表4所示,研究发现该方法具有良好的线性范围、较低的检出限。同时,相比于前处理过程,固相萃取、分散固相萃取等方法都需要使用耗电设备,主要体现在在萃取剂的分散[25-26]和萃取剂的分离[27]两个步骤,Li等[25]使用磁力搅拌仪进行Fe3O4@TiO2的分散,Mi等[26]采用离心吸取上层液的方法进行相分离。与之前前处理方法相比,该方法成功地实现了整个样品前处理过程不使用耗电设备,从而实现了现场样品处理,大大减少大量样品运输带来的不便,减少了人力和物力的消耗。因此,On-site DLLME-GC-ECD被证明是一种经济实用、简单方便的方法,能够用于现场处理环境水样中的5种拟除虫菊酯类杀虫剂。

表 4 与其他方法在水中拟除虫菊酯测定中的比较Table 4. Comparison of the proposed method and some other methods for pyrethroids determination in water方法

Method检测器

Detector萃取剂

Extraction

solvent线性范围

Range of linearity检出限

Limit of

detection/

(μg·L−1)是/否使用耗电设备

Yes/no use of

power-consuming

equipment是/否现场

Yes/no on-site参考文献

Reference固相萃取

Solid phase extraction高效液相色谱仪

HPLCFe3O4@TiO2 25 ~ 2 500 2.8 ~ 6.1 是 Yes 否 No [25] 分散固相萃取

Dispersive solid

phase extraction高效液相色谱仪

HPLCβ-环糊精连接的

超支化聚合物

CD-HBP5 ~ 500

10 ~ 5000.96 ~ 2.06 是 Yes 否 No [26] 固相萃取

Solid phase extraction气相色谱仪

GCFe3O4-NH2@MIL-101(Cr) 0.002 ~ 2.000 0.005 ~ 0.009 是 Yes 否 No [27] 现场分散液液微萃取

On-site DLLME气相色谱仪

GC己酸钠

Sodium hexanoate5 ~ 500 0.22 ~ 1.88 否 No 是 Yes 本工作

This work3. 结 论

本研究发了一种基于现场处理的分散液液微萃取气相色谱法测定环境水中的5种拟除虫菊酯类杀虫剂。该方法采用泡腾片辅助分散方式,选择可切换亲水性溶剂作为萃取剂。影响此方法的相关因素进行了优化,在最佳条件下,样品的加标回收率为88.2% ~ 113.0%,相对标准偏差为4.5% ~ 11.8%,检出限在0.22 ~ 1.88 μg/L之间,定量限在0.75 ~ 6.25 μg/L之间。富集倍数为65 ~ 108。该方法具有毒性低,污染小,环境友好的优点,同时在萃取剂分散和回收过程不需要用电设备,操作简便,方便现场操作,减少运输带来的不便。最后,该方法成功检测了3种环境水样,具有应用于现场处理的广阔潜力。

-

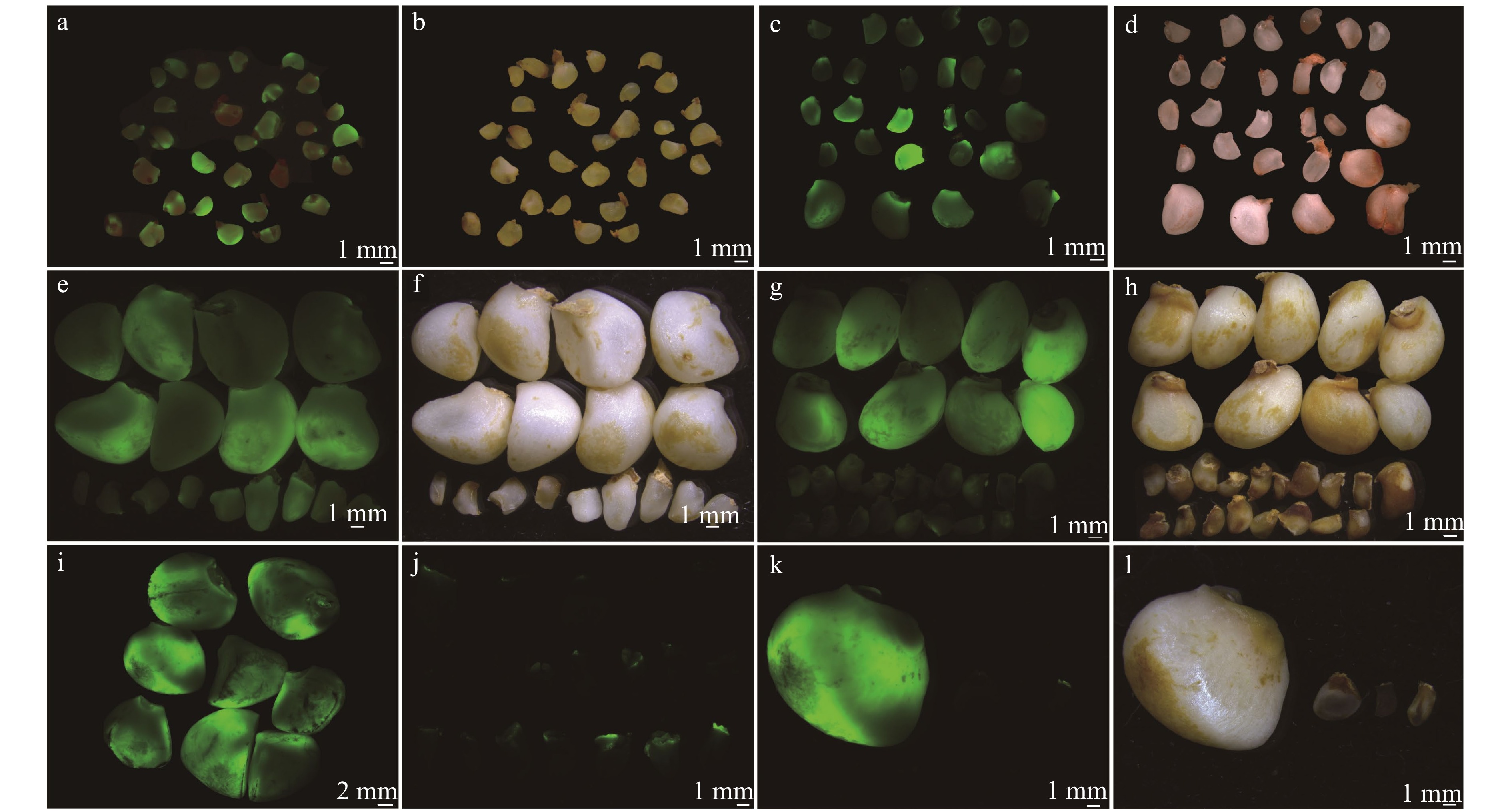

图 1 不同发育时期油茶的可育和败育胚珠形态变化以及败育率统计

a、f. 21 WAA胚珠;b、g. 26 WAA胚珠;c、h. 31 WAA胚珠;d、i. 34 WAA胚珠;e、j. 37 WAA胚珠; a ~ j.白色箭头指向表示正在败育的胚珠,红色箭头指向表示可育胚珠;k. 31 WAA胚珠,蓝色箭头和红色箭头指向表示正在败育的胚珠,黑色箭头指向表示可育胚珠;l. 31 WAA胚珠,从左至右依次为两种正在败育的胚珠和可育胚珠;m. 31、34、37 WAA油茶果实内败育胚珠的比例。标尺为2 mm。不同字母表示差异性显著(P < 0.05),下同。a, f, ovules of 21 WAA; b, g, ovules of 26 WAA; c, h, ovules of 31 WAA; d, i, ovules of 34 WAA; e, j, ovules of 37 WAA. a−j, the white arrow shows ovule aborting currently; the red arrow shows fertile ovule. k, ovules of 31 WAA, the blue and red arrows show ovules aborting currently; the black arrow shows fertile ovules. l, ovules of 31 WAA, there are two types of abortive ovules and fertile ovules from left to right. m, proportion of abortive ovules of 31, 34, 37 WAA. Bar is 2 mm. Different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05 level. The same below.

Figure 1. Morphological changes and proportion of fertile and abortive ovules of C. oleifera at different development stages

图 2 不同发育时期油茶胚珠活性观察

a、b. 21 WAA胚珠;c、d. 26 WAA胚珠;e、f. 31 WAA胚珠;g、 h. 34 WAA胚珠;i ~ l. 37 WAA胚珠;a、c、e、g、i、j、k. GFP通道;b、d、f、h、l. 明场;a ~ h. 1个子房内的所有胚珠;i. 一个子房内的所有可育胚珠;j. 一个子房内的所有败育胚珠;k、l. 一个子房内的部分可育胚珠和败育胚珠。a, b, ovules of 21 WAA; c, d, ovules of 26 WAA; e, f, ovules of 31 WAA; g, h, ovules of 34 WAA; i−l, ovules of 37 WAA; a, c, e, g, i, j, k, GFP field; b, d, f, h, l, bright field; a−h, all ovules in one ovary; i, all fertile ovules in one ovary; j, all abortive ovules in one ovary; k, l, partial fertile ovules and abortive ovules in one ovary.

Figure 2. Activity observation on ovules of C. oleifera at different development stages

图 3 不同发育时期油茶可育胚珠和败育胚珠的组织学观察

a. 31 WAA可育胚珠;b. 34 WAA可育胚珠;c. 37 WAA可育胚珠;d、e. 21 WAA败育胚珠;f~i. 26、31、34、37 WAA的败育胚珠;Ⅱ. 内珠被;OI. 外珠被;En. 胚乳;Cot. 子叶;VB. 维管束。a, fertile ovules of 31 WAA; b, fertile ovules of 34 WAA; c, fertile ovules of 37 WAA; d,e, abortive ovules of 21 WAA; f−i, abortive ovules of 26, 31, 34, 37 WAA; Ⅱ, inner integument; OI, outer integument; En, endosperm; Cot, cotyledon; VB, vascular bundle.

Figure 3. Histological observation on fertile and abortive ovules of C. oleifera at different developmental stages

图 4 不同发育时期油茶可育胚珠和败育胚珠的淀粉粒分布

a ~ f. 碘−碘化钾染色;g ~ l. PAS法染色;a、d、g、j. 31 WAA胚珠;b、e、h、k. 34 WAA胚珠;c、f、i、l. 37 WAA胚珠;a ~ c、g ~ i. 可育胚珠;d ~ f、j ~ l. 败育胚珠;S. 胚柄;黑色方框示淀粉粒。a−f, I2-KI staining; g−l, periodic acid-schiff staining; a, d, g, j, ovules of 31 WAA; b, e, h, k, ovules of 34 WAA; c, f, i, l, ovules of 37 WAA; a−c, g−i, fertile ovules; d−f, j−l, abortive ovules; S, suspensor. The black box shows starch grains.

Figure 4. Distribution of starch grains in fertile and abortive ovules of C. oleifera at different development stages

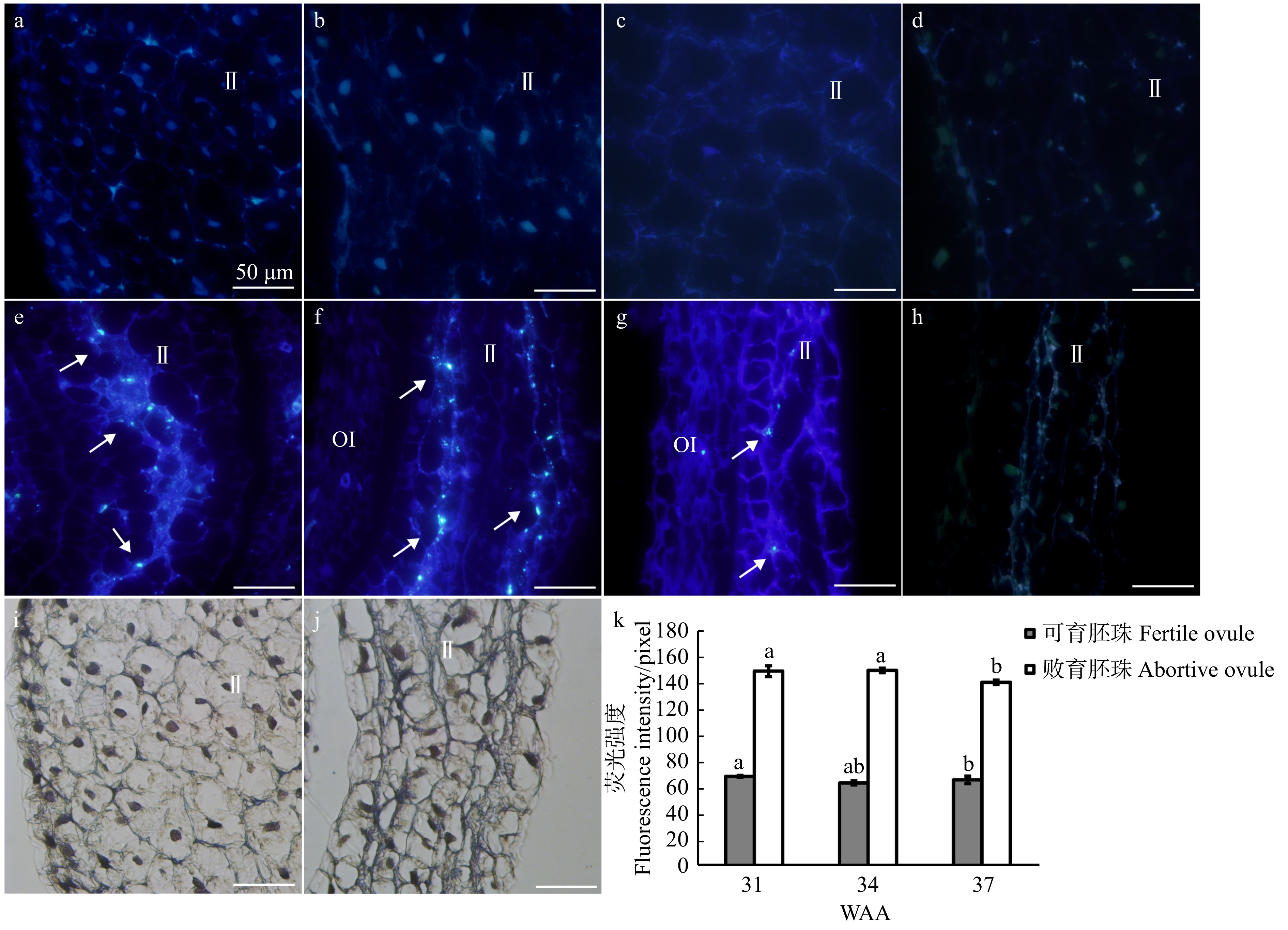

图 5 不同发育时期油茶可育胚珠和败育胚珠的胼胝质染色观察

a、e. 31 WAA胚珠;b、f. 34 WAA胚珠;c、g. 37 WAA胚珠;a ~ c. 可育胚珠的内珠被的胼胝质染色结果;d. 可育胚珠的内珠被的自发荧光;i. 可育胚珠的内珠被的明场;e ~ g. 败育胚珠的内珠被的胼胝质染色结果;h. 败育胚珠的内珠被的自发荧光;j. 败育胚珠的内珠被的明场;k. 胼胝质荧光信号的定量分析。标尺为50 μm。箭头指向表示胼胝质。a, e, ovules of 31 WAA; b, f, ovules of 34 WAA; c, g, ovules of 37 WAA; a−c, callose staining results of the inner integument of fertile ovules; d, autofluorescence of the inner integument of fertile ovules; i, bright field of the inner integument of fertile ovules; e−g, callose staining results of the inner integument of abortive ovules; h, autofluorescence of the inner integument of abortive ovules; j, bright field of the inner integument of abortive ovules; k, quantitative analysis of the florescent signal of callose. Bar is 50 μm. The arrow shows the callose.

Figure 5. Observation on callose staining of fertile and abortive ovules of C. oleifera at different development stages

图 6 CF在发育早期可育胚珠和败育胚珠中的运动情况

a ~ c. 可育胚珠;d ~ i. 败育胚珠;a、d、g. GFP通道;b、e、h. 明场;c、f、i. 叠加视野;标尺为250 μm。a−c, fertile ovules; d−i, abortive ovules; a, d, g, GFP field; b, e, h, bight field; c, f, i, merged field; Bar is 250 μm.

Figure 6. CF movement in fertile and abortive ovules of C. oleifera at early development stage

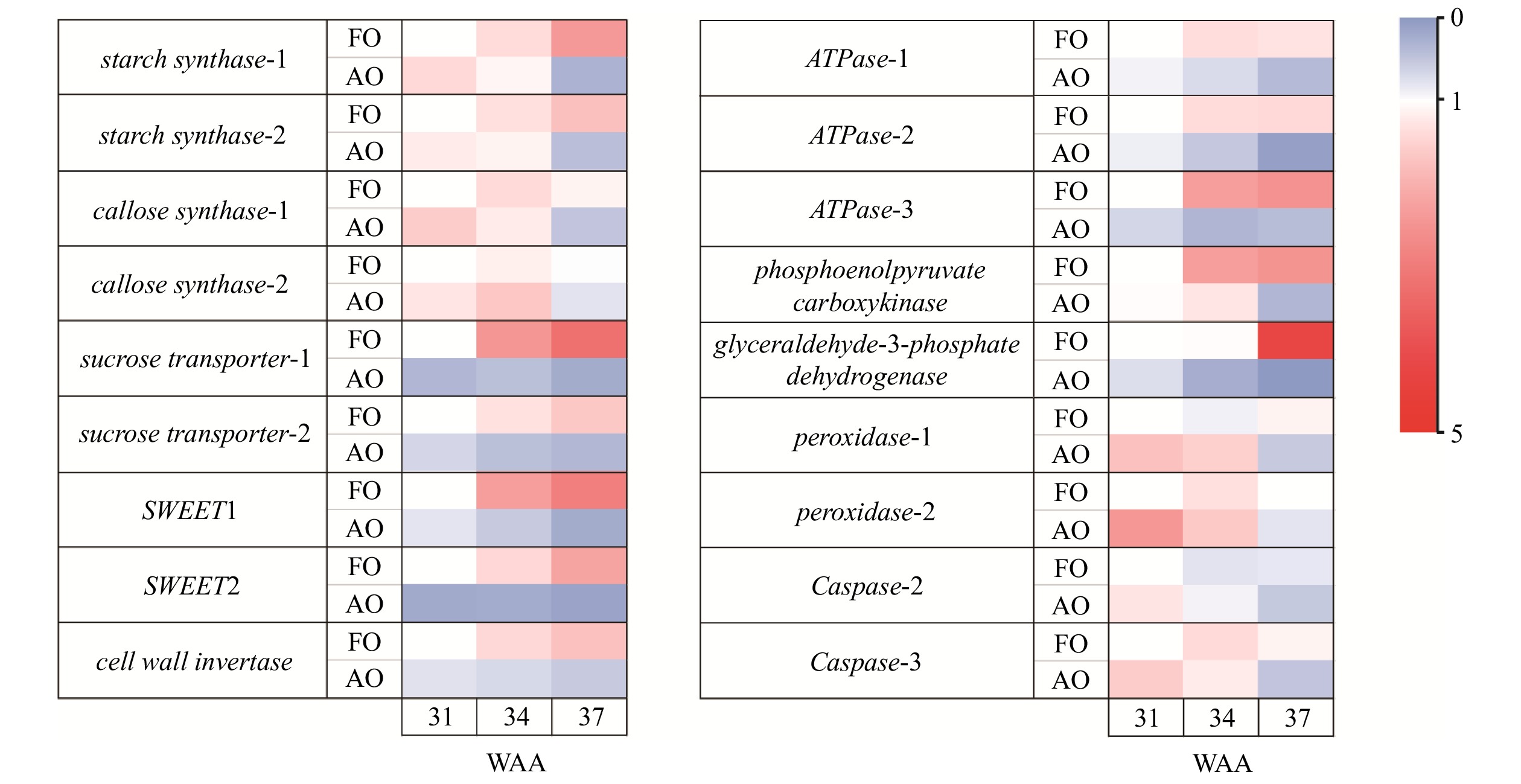

图 7 不同发育时期可育胚珠和败育胚珠中与糖和能量代谢、活性氧代谢和细胞凋亡过程相关基因的表达情况

FO. 可育胚珠;AO. 败育胚珠。FO, fertile ovules; AO, abortive ovules.

Figure 7. Heatmap of the relative expressions of genes about sugar and energy metabolism, reactive oxygen metabolism and apoptosis processes of fertile and abortive ovules of C. oleifera at different stages

表 1 实时荧光定量PCR试验所用引物

Table 1 Primers used in qRT-PCR experiment

基因

Gene上游引物序列(5′—3′)

Forward primer (5′−3′)下游引物序列(5′—3′)

Reverse primer (5′−3′)starch synthase-1 TGGACCGTGGGATGCCTTAT TCAATGGAATGCAGCAATAGCC starch synthase-2 AGGAGAGAGAAGGGAAAGATCC AATAGTTCGGTTTCTGCCATGAAG callose synthase-1 AGTTGGTATCGATGGGCAGA TGCTTGACCAAGTAGAAGAAGG callose synthase-2 ATGGGTAGGAAGAAGTTCAGTGC CCACAGATCCAATAAACAGGAA sucrose transporter-1 ATCCGGGTGCCTTACAAGAA AACTGGAAGGCAGATCGGAG sucrose transporter-2 AGCCGATCGCCGCCGTACTA CTGTATTCCGCAAGCCACTG SWEET1 AGGAGAGAGAAGGGAAAGATCC AATAGTTCGGTTTCTGCCATGAAG SWEET2 GTTGTTGCGAAAGATCAAAAGTT TTCTTGACATGCGATTGAGCTAA cell wall invertase CCAAGTTGACATGCCTAGCAC ATTAACCCAAATGGTCCAACCT ATPase-1 ATATCTGATGAGAACATGCAAGAGAA TTACTGGAACATACACTTAGGCAGGA ATPase-2 AATTCGATGACCTTTCAGAGC TTTAAGCAGCAGATTCCTTGG ATPase-3 GGAGGCTGCTGTCCTCTCTCT GGTGGCGTAGTCGAGGACA phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase GGAATGGACTGGGGAAGATAC GCCAAAGACGCACTCTTCTTC glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase CTCCCTCTCTCTATCTGTCCCTCT GATCCTTCCGAATCCATTG peroxidase-1 TGGCTTTTAACCTCTCAGCTGTTT TGGTGATGTGAAGATGAATATGATGA peroxidase-2 ATGTATTTGTGGAGCTTCAGCACT CCATGCTTTGAGAAGCAGGAGG Caspase-2 AGCTGTACGTTGTGATTCTGCT CAGCTCTGGGGTTTCCATT Caspase-3 CACCGTTTCTGTCTCCTCTTC GGTCGGAGTTCAACTGATGG EF-2 AAGCTGCTGGCGTGAGAATA CTCTCTTCTGCTGCCTTCTT -

[1] 王小艺, 曹一博, 张凌云, 等. 油茶生长发育过程中脂肪酸成分的测定分析[J]. 中国农学通报, 2012, 28(13): 76−80. doi: 10.11924/j.issn.1000-6850.2012-0460 Wang X Y, Cao Y B, Zhang L Y, et al. Analysis of the fatty acids compositions of Camellia in different growth stages[J]. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin, 2012, 28(13): 76−80. doi: 10.11924/j.issn.1000-6850.2012-0460

[2] 梁文静, 肖萍, 崔萌, 等. 油茶果实和种子生长发育的动态[J]. 南昌大学学报(理科版), 2019, 43(1): 46−52. Liang W J, Xiao P, Cui M, et al. The growth and development dynamics of Camellia oleifera Abel. fruits and seeds[J]. Journal of Nanchang University (Natural Science), 2019, 43(1): 46−52.

[3] 曹慧娟. 油茶胚胎学的观察[J]. 植物学报, 1965, 13(1): 44−60. Cao H J. Observation of Camellia embryology[J]. Acta Botanica Sinica, 1965, 13(1): 44−60.

[4] 周良骝, 任立中, 陈佩聪, 等. 油茶胚胎发育及落花落果的研究[J]. 安徽农学院学报, 1991, 18(3): 238−241. Zhou L L, Ren L Z, Chen P C, et al. Premature drop shedding and embryonic development of petals of the oil-tea Camellia[J]. Journal of Anhui Agricultural College, 1991, 18(3): 238−241.

[5] 邹锋. 攸县油茶生殖生物学研究[D]. 长沙: 中南林业科技大学, 2010. Zou F. The researches on reproductive biology of Camellia yubsienensis Hu. [D]. Changsha: Central South University of Forestry and Technology, 2010.

[6] Gao C, Yang R, Yuan D Y. Characteristics of developmental differences between fertile and aborted ovules in Camellia oleifera[J]. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 2017, 142(5): 330−336. doi: 10.21273/JASHS04164-17

[7] 梁春莉, 刘孟军, 赵锦. 植物种子败育研究进展[J]. 分子植物育种, 2005, 3(1): 117−122. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-416X.2005.01.020 Liang C L, Liu M J, Zhao J. Research progress on plant seeds abortion[J]. Molecular Plant Breeding, 2005, 3(1): 117−122. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-416X.2005.01.020

[8] Liu J F, Cheng Y Q, Yan K, et al. The relationship between reproductive growth and blank fruit formation in Corylus heterophylla Fisch[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2012, 136: 128−134. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2012.01.008

[9] 闫晓娜. 扇脉杓兰种子败育机理的研究[D]. 北京: 中国林业科学研究院, 2015. Yan X N. Study on the mechanism of seed abortion in Cypripedium japonicum[D]. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Forestry, 2015.

[10] 张超越, 王迎夏, 郑艳艳, 等. 西瓜种子败育的胚胎学观察[J]. 中国瓜菜, 2019, 32(8): 134−138. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-2871.2019.08.032 Zhang C Y, Wang Y X, Zheng Y Y, et al. Embryological observations on seed abortion in watermelon[J]. China Cucurbits and Vegetables, 2019, 32(8): 134−138. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-2871.2019.08.032

[11] 张懿, 张大兵, 刘曼. 植物体内糖分子的长距离运输及其分子机制[J]. 植物学报, 2015, 50(1): 107−121. Zhang Y, Zhang D B, Liu M. Long-distance transport of sugar in plants and molecular mechanism[J]. Acta Botanica Sinica, 2015, 50(1): 107−121.

[12] Cheng J T, Wen S Y, Xiao S, et al. Overexpression of the tonoplast sugar transporter CmTST2 in melon fruit increases sugar accumulation[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2018, 69(3): 511−523. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx440

[13] Wang L, Ruan Y L. New insights into roles of cell wall invertase in early seed development revealed by comprehensive spatial and temporal expression patterns of GhCWIN1 in cotton[J]. Plant Physiology, 2012, 160(2): 777−787. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.203893

[14] Werner D, Gerlitz N, Stadler R. A dual switch in phloem unloading during ovule development in Arabidopsis[J]. Protoplasma, 2011, 248(1): 225−235. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0223-8

[15] 张春吉. 榛子胚败育过程中物质运输障碍发生规律及基因差异表达谱研究[D]. 四平: 吉林师范大学, 2014. Zhang C J. Studies on material transport barriers and its differential gene expression profiles in the process of embryo abortion of hazelnut[D]. Siping: Jilin Normal University, 2014.

[16] Rosellini D, Lorenzetti F, Bingham E T. Quantitative ovule sterility in Medicago sativa[J]. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 1998, 97(8): 1289−1295. doi: 10.1007/s001220051021

[17] Rosellini D, Ferranti F, Barone P, et al. Expression of female sterility in alfalfa (Medicago sativa)[J]. Sexual Plant Reproduction, 2003, 15(6): 271−279. doi: 10.1007/s00497-003-0163-y

[18] Gong Z X, Han R, Xu L, et al. Combined transcriptome analysis reveals the ovule abortion regulatory mechanisms in the female sterile line of Pinus tabuliformis Carr.[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(6): 3138−3159. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063138

[19] 曾维英, 杨守萍, 喻德跃, 等. 大豆质核互作雄性不育系NJCMS2A及其保持系的花药蛋白质组比较研究[J]. 作物学报, 2007, 33(10): 1637−1643. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0496-3490.2007.10.012 Zeng W Y, Yang S P, Yu D Y, et al. A comparative study on anther proteomics between cytoplasmic-nuclear male sterile line NJCMS2A and its maintainer of soybean[J]. Acta Agronomica Sinica, 2007, 33(10): 1637−1643. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0496-3490.2007.10.012

[20] 贾晋, 张鲁刚. 萝卜胞质雄性不育正常花蕾与败育花蕾DD-PCR及EST序列分析[J]. 核农学报, 2008, 22(4): 426−431. Jia J, Zhang L G. mRNA differential display and est sequence analysis of aborted bud and normal bud in radish (Raphanus sativus)[J]. Journal of Nuclear Agricultural Sciences, 2008, 22(4): 426−431.

[21] 王永平, 王莉, 陈鹏, 等. 银杏种实发育过程中中种皮的解剖与超微结构观察[J]. 植物生理学通讯, 2006, 42(6): 1086−1090. Wang Y P, Wang L, Chen P, et al. Observation on anatomical structure and ultra-structure of mesocoat during development of Ginkgo biloba L.[J]. Plant Physiology Journal, 2006, 42(6): 1086−1090.

[22] 杜兵帅. 板栗胚珠败育的细胞学及分子机理初探[D]. 北京: 北京农学院, 2020. Du B S. The preliminary study on cytological and molecular mechanism of ovule abortion in Chinese chestnut[D]. Beijing: Beijing University of Agriculture, 2020.

[23] 谭晓风, 袁德义, 袁军, 等. 大果油茶良种‘华硕’[J]. 林业科学, 2011, 47(12): 184−209. doi: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20111228 Tan X F, Yuan D Y, Yuan J, et al. An elite variety: Camellia oleifera ‘Huashuo’[J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2011, 47(12): 184−209. doi: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20111228

[24] Zhang L Y, Peng Y B, Pelleschi-Travier S, et al. Evidence for apoplasmic phloem unloading in developing apple fruit[J]. Plant Physiology, 2004, 135(1): 574−586. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.036632

[25] 李和平. 植物显微技术[M]. 2版. 北京: 科学出版社, 2009. Li H P. Plant microscopy[M]. 2nd ed. Beijing: Science Press, 2009.

[26] 姜金仲, 李云, 贺佳玉, 等. 四倍体刺槐胚珠败育及其机制[J]. 林业科学, 2011, 47(5): 40−45. doi: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20110506 Jiang J Z, Li Y, He J Y, et al. Ovule abortion and its mechanism for tetraploid Robinia pseudoacacia[J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2011, 47(5): 40−45. doi: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20110506

[27] 张健, 吕柳新, 叶明志. 胚胎败育型荔枝胚胎发育异常的显微及亚显微观察[J]. 河南农业大学学报, 2006, 40(2): 194−197. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-2340.2006.02.020 Zhang J, Lü L X, Ye M Z. Microscopic and submicroscopic observations on the abnormal embryonic development of embryo-abortive litchi(Litchi chinensis Sonn. cv. luhebao)[J]. Journal of Henan Agricultural University, 2006, 40(2): 194−197. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-2340.2006.02.020

[28] Du B S, Zhang Q, Cao Q Q, et al. Morphological observation and protein expression of fertile and abortive ovules in Castanea mollissima[J]. Peer J, 2021, 9: e11756

[29] Wang X J, Li X X, Zhang J W, et al. Characterization of nine alfalfa varieties for differences in ovule numbers and ovule sterility[J]. Australian Journal of Crop Science, 2011, 5(4): 447−452.

[30] Zhou H C, Jin L, Li J, et al. Altered callose deposition during embryo sac formation of multi-pistil mutant (mp1) in Medicago sativa[J]. Genetics and Molecular Research, 2016, 15(2): 10.4238.

[31] Swanson R, Edlund A F, Preuss D. Species specificity in pollen-pistil interactions[J]. Annual Review of Genetics, 2004, 38: 793−818. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092356

[32] 袁艺, 杜国华, 谢中稳, 等. 板栗空篷发生的主要营养物质的变化[J]. 武汉植物学研究, 1997, 15(3): 243−249. Yuan Y, Du G H, Xie Z W, et al. Changes of some main nutritional substances during the development course of empty-shell chestnut[J]. Journal of Wuhan Botanical Research, 1997, 15(3): 243−249.

[33] 文李, 刘盖, 张再君, 等. 红莲型水稻细胞质雄性不育花药蛋白质组学初步分析[J]. 遗传, 2006, 28(3): 311−316. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0253-9772.2006.03.011 Wen L, Liu G, Zhang Z J, et al. Preliminary proteomics analysis of the total proteins of hl type cytoplasmic male sterility rice anther[J]. Hereditas, 2006, 28(3): 311−316. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0253-9772.2006.03.011

[34] Osorio S, Vallarino J G, Szecowka M, et al. Alteration of the interconversion of pyruvate and malate in the plastid or cytosol of ripening tomato fruit invokes diverse consequences on sugar but similar effects on cellular organic acid, metabolism, and transitory starch accumulation[J]. Plant Physiology, 2013, 161(2): 628−643. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.211094

[35] 刘静, 张鲁刚, 王风敏, 等. 萝卜花蕾败育过程中的组织细胞学特征观察[J]. 西北农业学报, 2008, 17(5): 272−276. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-1389.2008.05.059 Liu J, Zhang L G, Wang F M, et al. Observation of histocytological feature on radish flower bud during aborting[J]. Acta Agriculturae Boreali-occidentalis Sinica, 2008, 17(5): 272−276. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-1389.2008.05.059

[36] 位明明, 王俊生, 张改生, 等. GAPDH基因表达与小麦生理型雄性不育花药败育的关系[J]. 分子植物育种, 2009, 7(4): 679−684. doi: 10.3969/mpb.007.000679 Wei M M, Wang J S, Zhang G S, et al. Relationship between the expression of GAPDH gene and anther abortion of physiological male sterile of wheat[J]. Molecular Plant Breeding, 2009, 7(4): 679−684. doi: 10.3969/mpb.007.000679

[37] 刘浩, 柳燕贞, 王静, 等. ‘白核’龙眼种子败育不同时期差异蛋白分析[J]. 园艺学报, 2009, 36(12): 1725−1732. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0513-353X.2009.12.002 Liu H, Liu Y Z, Wang J, et al. Analysis of differentially expressed proteins during the different states of longan seed abortion[J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 2009, 36(12): 1725−1732. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0513-353X.2009.12.002

-

期刊类型引用(4)

1. 李桂,曹文华,马建业,马波,王阳修,王秋月. 小麦秸秆覆盖量对坡面流水动力学特性影响. 农业工程学报. 2023(01): 108-116 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 安妙颖,韩玉国,王金满,徐磊,王秀茹,庞丹波. 黄土丘陵区坡面薄层水流动力学特性及其对土壤侵蚀的影响. 中国农业大学学报. 2020(02): 142-150 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 李志刚,梁心蓝,黄洪粮,李和谋,赵小东. 坡耕地地表起伏对坡面漫流的影响. 水土保持学报. 2020(02): 71-77+85 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 杨坪坪,李瑞,盘礼东,王云琦,黄凯,张琳卿. 地表粗糙度及植被盖度对坡面流曼宁阻力系数的影响. 农业工程学报. 2020(06): 106-114 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(27)

下载:

下载: