Soil organic carbon stabilization and formation: mechanism and model

-

摘要: 土壤有机碳对自然气候解决方案的贡献可以达到25%,提高土壤碳储量是实现“碳中和”的重要途径。合理的土壤有机碳管理和精准的模型预测依赖于对土壤碳循环过程的清晰认识。然而,土壤有机碳的长期保存机制、来源和环境调控作用还不清楚。本文系统评述了土壤有机碳稳定(生化难分解性、矿物保护和团聚体保护)和形成(腐质化、微生物效率−基质稳定框架和微生物碳泵理论)的前沿理论和机制,在此基础上分析了目前土壤碳循环模型的发展(Century模型、微生物模型和微生物−矿物模型),并提出了未来试验和模型研究中亟需解决的关键科学问题。Abstract: Soil organic carbon (SOC) represents 25% of the potential of natural climate solutions, improvement of SOC storage is a critical pathway to realize “carbon neutralization”. Reasonable SOC management and accurate model prediction require deep understanding of soil carbon cycling processes. However, the persistence mechanism of SOC, pathways controlling SOC formation, and their environmental regulations are not clear. Here, we first synthesized the frontier theories and mechanisms of SOC stabilization (biochemical recalcitrance, mineral protection, and aggregation protection) and formation (humification, microbial efficiency-matrix stabilization framework, and microbial carbon pump theory); we then reviewed the development of soil carbon cycling models (Century model, microbial model, and microbial-mineral model); we finally proposed the urgent scientific question for future experimental and modelling studies.

-

土壤具有养分供给、植被生产力维持、土壤生物栖息地提供、有机碳固持、污染物降解等多种生态系统服务功能[1-2]。因为绝大多数土壤功能都依赖于土壤有机碳,所以有机碳固持是土壤多功能性的核心[3]。比如:有机碳含量高的土壤具有高的持水力[4]、养分可利用性[5]和粮食生产力[6];土壤有机碳是土壤食物网的能源基础,维持着多维度的土壤生物多样性[7]。全球2 m深度土壤碳储量为2 060亿吨,远超大气碳库和植被碳库之和,其微小波动就能引起大气二氧化碳(CO2)浓度的显著变化[8]。土壤有机碳对自然气候解决方案的贡献可以达到25%[9]。因此,通过合理的生态系统管理措施提升土壤碳汇功能是实现“碳中和”的重要途径[10]。

土壤碳汇功能的提升与预测依赖于对土壤有机碳形成和稳定的清晰认识[10]。国内外学者在土壤有机碳形成和稳定理论研究方面取得一系列突破性进展,但距离真实模拟土壤有机碳动态和精准预测土壤有机碳对气候变化的响应和反馈还需开展大量研究工作。本文将系统评述土壤有机碳稳定和形成机制,在此基础上,系统分析目前土壤碳循环的模型研究进展,并提出未来试验和模型研究中亟需解决的关键科学问题。

1. 土壤有机碳稳定机理

土壤有机碳稳定性是指土壤避免碳丢失的能力,稳定性高的土壤不易通过矿化(气态形式的CO2和CH4)和淋溶(液态形式的溶解性有机碳)等途径释放碳[11]。土壤有机碳稳定性的重要衡量指标为矿化潜力和周转时间。矿化潜力的最优评估方法是特定水热条件下的室内矿化培养测定的CO2累积释放量,并标准化到单位有机碳含量上[12]。有机碳周转时间可以利用上述矿化培养数据通过模型反演获得,也可利用同位素标记法进行量化[13]。同位素标记法包括稳定碳同位素(13C)自然丰度法、稳定碳同位素标记法以及核爆放射性碳同位素(14C)法。自然丰度法依赖于C3和C4植物具有不同的13C分馏作用,通过C3和C4植物替换过程中植物和土壤13C信号的变化计算土壤有机碳的周转时间。稳定碳同位素标记法是通过向土壤添加13C标记的植物材料追踪外源碳在土壤中的转化和周转。核爆放射性碳同位素法根据14C的衰变规律和大气14C信号计算土壤有机碳的年龄。Feng等[13]同时利用矿化培养数据的模型反演、自然13C丰度法和核爆14C法研究了不同土壤粒级有机碳的周转时间,发现矿化培养法揭示的周转时间最短,而核爆14C法揭示的周转时间最长。

土壤有机碳稳定性研究长期以来都是全球变化和土壤学领域的关键科学问题,但对土壤有机碳稳定机制的划分却不尽相同。例如,Sollins等[11]将土壤有机碳稳定机制划分为有机碳顽固性、相互作用和有机碳可获取性3个方面。von Lützow等[14]将土壤有机碳稳定机制划分为选择性保留、空间不可获取性和有机碳与矿物/金属离子的相互作用3个方面。然而,Mayer[15]建议将稳定机制划分为顽固性和生物排斥2个方面。最近,越来越多的研究强调矿物结合有机碳在土壤有机碳稳定性、气候变化敏感性、土壤碳饱和以及生态系统模型中的关键作用[16-18]。因此,Angst等[19]最近将有机碳稳定机制划分为生化难分解性、形成矿物结合有机碳和形成土壤团聚体3个方面。综上,本文中稳定机制的划分标准参考Angst等[19]的方法,具体分为有机碳的自身生化难分解性、矿物保护和团聚体保护3个方面。生化难分解性决定有机碳固有分解速率,而矿物保护和团聚体保护则是通过降低微生物对有机碳的可获取性来降低有机碳的分解速率。

1.1 生化难分解性

土壤有机碳是植物残体经动物和微生物分解后长期累积的复杂混合物,由一系列分子结构从简单到复杂的有机物组成的连续复合体[20-23]。例如:有分子结构简单、分解迅速的单糖和氨基酸;有结构复杂、分解缓慢的木质素和角质;也有分解速度中等的纤维素。土壤有机碳的生化难分解性指有机碳自身惰性组分含量大小,即惰性组分比例越大,有机碳生化难分解性越强,分解越慢[24]。土壤中主要稳定有机碳组分为植物源蜡质脂类、角质、软木质、木质素等[25-26]和微生物源的氨基葡萄糖、胞壁酸和甘油二烷基四醚脂类化合物[27]。这些难分解的生物大分子可以在土壤中长期保留原始结构特征,分别被称为植物源有机碳和微生物源有机碳的标志物,是土壤稳定性有机碳库的重要组成部分[22]。Gunina等[28]的最新观点认为:土壤中这些顽固性有机碳的累积是因为微生物将进入土壤的大部分植物源碳作为能量而不是碳源,而土壤有机碳作为分解剩余副产品积累起来,这是由于微生物分解顽固性有机碳所需要投资的能量超过了其自身能量的收益。因此,从能量角度探讨土壤有机碳的形成可能是一个潜在的有效路径[28]。

1.2 矿物保护

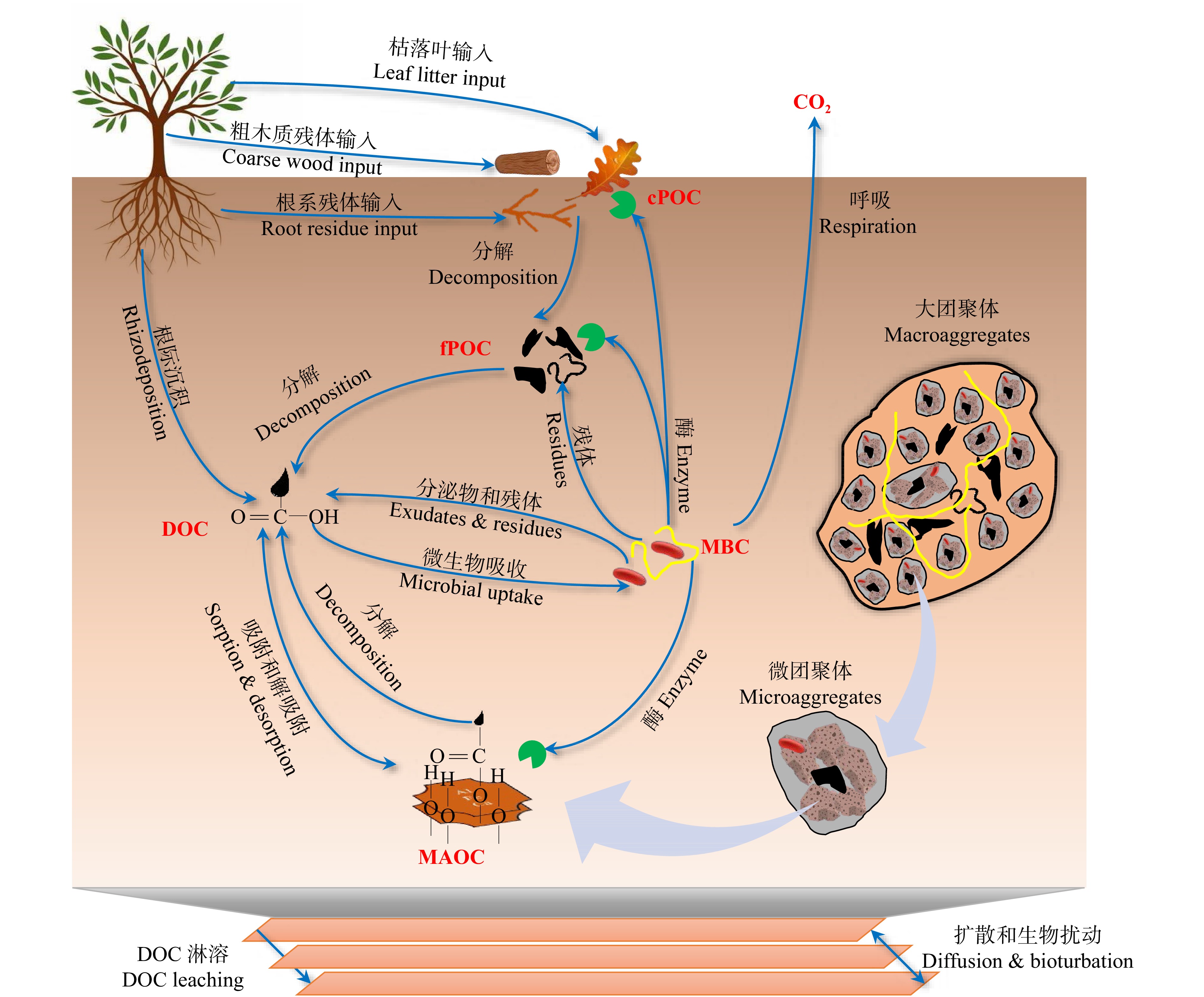

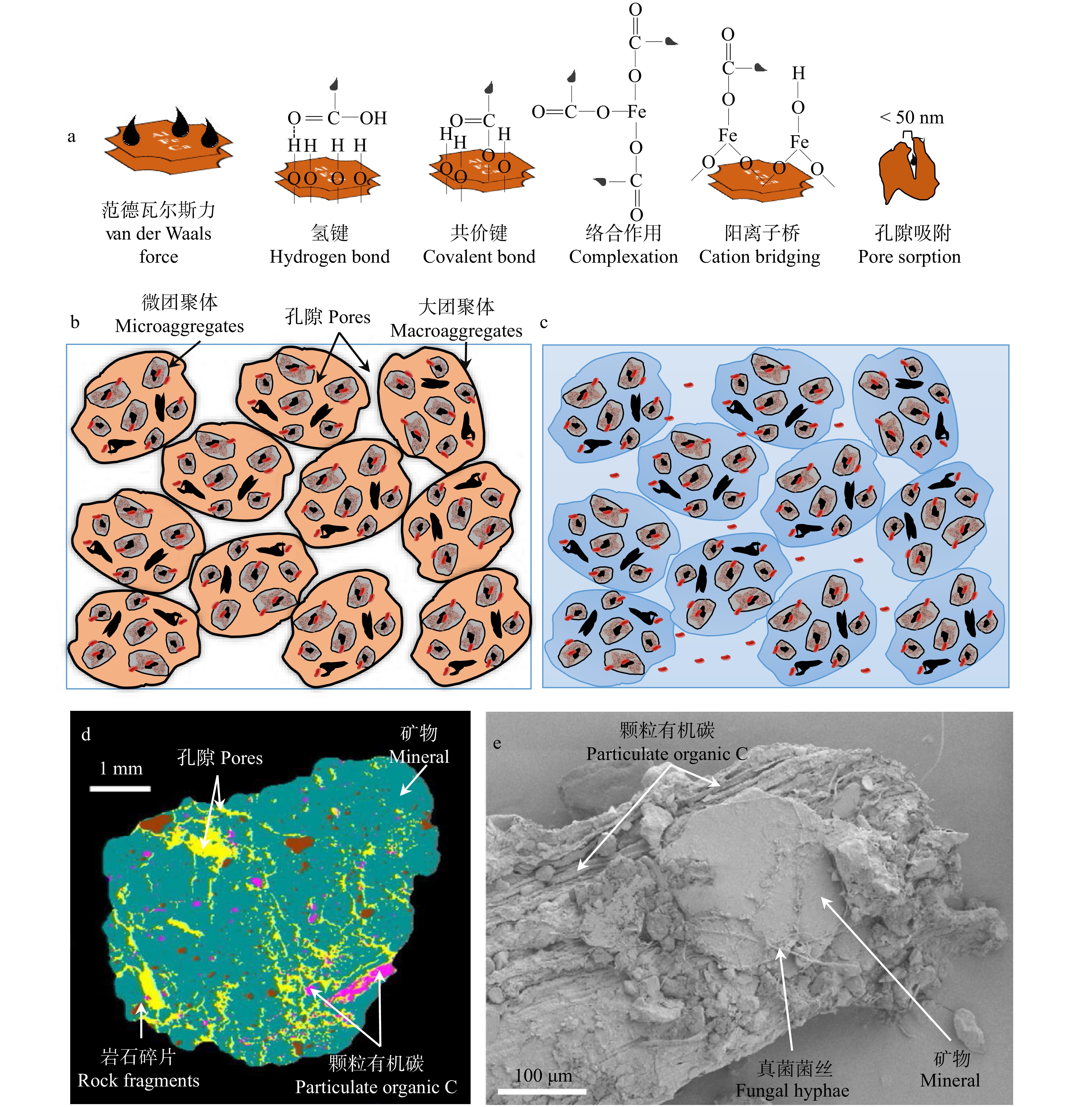

尽管低分子量的溶解性有机碳自身化学顽固性很低,很容易被微生物同化吸收。然而,这些低分子量物质却可以通过形成矿物结合有机碳在土壤中保留上千年。例如:Wattel-Koekkoek等[29]利用14C技术发现稀树草原土壤蒙脱石结合有机碳的年龄可以达到1 000年,而高岭石结合有机碳的年龄也可达到360年。有机碳和矿物的结合主要包括表面吸附和中微孔吸附。表面吸附主要通过范德瓦尔斯力、氢键、共价键、络合作用和阳离子桥5种主要方式结合(图1)[14,30]。范德瓦尔斯力是原子或中性分子彼此距离非常近时产生的一种微弱电磁引力,这是一个所有原子之间普遍存在的物理结合力。氢键是指矿物颗粒表面带部分正电荷的氢原子和有机碳中带部分负电荷的氧原子或者氮原子间的相互作用力。共价键是矿物和有机碳通过配体交换实现相互结合的过程。例如:矿物表面的质子化羟基可以和有机碳的醇羟基或酚羟基或羧基通过释放一个水分子形成新的共价键紧密结合在一起[31]。矿物和有机碳之间结合的稳定性大小依次为:范德瓦尔斯力 < 氢键 < 共价键。络合作用指土壤溶液中的游离金属阳离子和有机碳以配位键缔合成络合物,其中,类似芳香环的螯合物是一种高稳定性的金属−有机复合物[32]。阳离子桥是指土壤溶液中的游离金属阳离子充当桥梁作用将矿物和有机碳结合在一起形成稳定矿物结合有机碳[33]。

![]() 图 1 土壤有机碳的矿物保护和团聚体保护a. 矿物保护机制;b,c. 干旱和湿润条件下土壤团聚体间的隔离情况,参考Wilpiszeski等[34]绘制;d. 团聚体孔隙对有机碳的闭蓄保护作用(图片来源于Schlüter等[35]);e. 新鲜凋落物−矿物界面(电镜扫描照片来源于Witzgall等[36])。a, mechanisms of mineral protection; b and c, the isolation of soil aggregates under dry and wet conditions, referring to Wilpiszeski, et al.[34]; d, occlusion of soil organic carbon by aggregation (image from Schlüter, et al.[35]); e, scanning electron microscopy image of the interface of plant litter and soil minerals (image from Witzgall, et al.[36]).Figure 1. Mineral and aggregate protection of soil organic carbon

图 1 土壤有机碳的矿物保护和团聚体保护a. 矿物保护机制;b,c. 干旱和湿润条件下土壤团聚体间的隔离情况,参考Wilpiszeski等[34]绘制;d. 团聚体孔隙对有机碳的闭蓄保护作用(图片来源于Schlüter等[35]);e. 新鲜凋落物−矿物界面(电镜扫描照片来源于Witzgall等[36])。a, mechanisms of mineral protection; b and c, the isolation of soil aggregates under dry and wet conditions, referring to Wilpiszeski, et al.[34]; d, occlusion of soil organic carbon by aggregation (image from Schlüter, et al.[35]); e, scanning electron microscopy image of the interface of plant litter and soil minerals (image from Witzgall, et al.[36]).Figure 1. Mineral and aggregate protection of soil organic carbon以上5种矿物和有机碳的结合不是孤立存在的。首先,某个有机碳分子具有多个配体和多个氢键结合位点,使其可以通过多种方式和矿物结合。例如:葡萄糖酸可以通过氢键、阳离子桥和共价键途径和矿物结合[30]。其次,土壤中的矿物会形成一系列复杂的有机碳结合位点。例如:金属氧化物和层状硅酸盐微晶边缘的可变电荷表面携带羟基,这些羟基随着pH值的降低而质子化,会通过快速配体交换使有机配体得以保留;当土壤溶液中的pH值升高时,氢键和范德华力将是矿物结合有机碳的主要驱动力[30,37]。当有机碳亲水的羟基或羧基和矿物结合后,其疏水官能团会排列在矿物结合有机碳的表面,疏水性降低了表面润湿性,从而导致分解率降低,因为缺水会直接限制微生物活性[14]。最后,范德瓦尔斯力、氢键、共价键、络合作用和阳离子桥5种结合方式在矿物表面可以形成多层复杂的矿物结合有机碳[38]。例如:和矿物表面通过共价键结合的有机分子可以在外层再次通过阳离子桥作用和其他的有机分子结合,进而形成复层结构。

多数矿物表面都充满孔隙,如层状硅酸盐的层间孔隙、水铁矿的孔隙结构[39]。按照矿物表面孔隙大小可以将孔隙分为微孔(< 2 nm)、中孔(2 ~ 50 nm)和大孔(> 50 nm)[39]。科学家们保守评估,当孔隙小于20 nm时,微生物分泌的水解酶将不能进入微孔隙利用保存在孔隙中的有机碳[40-42]。但在实际情况下,孔隙小于50 nm时,也可以很好的阻隔微生物的分解[40-42]。总之,不同矿物具有不同的表面积、孔隙结构、配体、粒径、结晶情况等特征,土壤中的有机碳种类丰富多样,其与矿物的结合对温度、pH值等都具有不同的响应,涉及一系列复杂、动态的物理化学过程[14,30]。

1.3 团聚体保护

上述矿物吸附作用形成的矿物−有机碳复合体并不是孤立存在的,会进一步结合形成大小不一的多孔土壤团聚体,团聚体内部颗粒间聚合力要比团聚体之间的聚合力大,进而保证团聚体能够在土壤中稳定存在[36]。土壤团聚体的形成是生物、非生物和环境因子共同作用的结果。土壤团聚体和微生物密不可分:一方面,土壤团聚体是微生物栖息地;另一方面,土壤微生物是土壤团聚体形成的重要生物因素[43]。超过90%的土壤细菌生活在大团聚体中(> 0.25 mm),这其中的70%生活在小团聚体中(< 0.25 mm),微生物定居的面积不到团聚体总面积的1%[36]。团聚体的破坏会显著增加有机碳的分解[36,44-45]。例如:Barreto等[46]发现 > 8 mm、2 ~ 8 mm和0.25 ~ 2.00 mm的森林土壤团聚体破坏后,有机碳的矿化速率分别是相应未破坏团聚体的878%、300%和345%。团聚体可以通过多种闭蓄机制提高有机碳的稳定性(图1)。首先,团聚体会在微生物和底物之间起到物理隔离作用;其次,团聚体中的微生物和酶的扩散能力受到限制,抑制了微生物的资源可利用性;最后,在毫米级的团聚体中,氧气浓度存在明显的梯度,团聚体内部的微生物会受到氧气限制而具有较低的分解速度[14,47]。当土壤孔隙中水分增加时,团聚体的物理隔离作用会受到削弱,微生物、酶和溶解性有机碳在团聚体之间的流通性会增加(图1)[36]。此外,Witzgall等[36]最近利用扫描电镜发现:矿物会在新鲜的植物残体表面覆盖,进而阻止植物残体和微生物接触,增加新鲜植物残体在土壤中的保存时间(图1)。

2. 土壤有机碳的形成机制

传统观点认为土壤有机碳的形成是植物残体的腐殖化过程。随着土壤分析技术的发展,越来越多的证据表明微生物死亡残体也是土壤有机碳的重要来源。例如:Wang等[48]最新全球评估发现:农田、草地和森林表层土壤中微生物残体碳对有机碳的平均贡献分别为51%、47%和35%,证实微生物残体是土壤有机碳的重要来源。此外,土壤有机碳的化学顽固性常常被发现和植物残体的顽固性解耦[49]。因此,目前关于有机碳的形成机制比较成熟的两个理论框架是微生物效率−基质稳定(microbial efficiency-matrix stabilization)[49]和土壤微生物碳泵(soil microbial carbon pump)[50]。

2.1 微生物效率−基质稳定理论框架

微生物效率−基质稳定理论框架的提出,标志着对土壤有机碳形成研究进入新的历史阶段[49,51]。微生物效率−基质稳定理论框架有2个核心涵义:(1)土壤微生物在土壤有机碳形成过程中扮演着过滤器的作用,强调微生物碳利用效率、分配和周转等生理特征对植物残体碳去向和组分的调控作用;(2)土壤基质(矿物)固有属性决定着有机碳在土壤中的长期储存(即上述的矿物保护机制)。

腐殖化土壤有机碳形成机制认为凋落物的化学顽固性决定土壤有机碳的稳定性,即凋落物难降解物质越多(质量低),越有利于土壤有机碳的固持和稳定[14,49]。微生物只能同化吸收小分子有机物,因为微生物的细胞壁只能允许分子量小于600 ~ 1 000 Da的小分子有机物通过[52]。因此,微生物会通过释放胞外酶,将大分子的植物残体降解为可溶性有机碳后才能同化利用。微生物效率−基质稳定理论框架认为:凋落物质量越高,分解越快,微生物具有较高的碳利用效率,越有利于微生物通过残体形式向土壤输入有机碳[49]。并假设微生物源溶解性有机碳和矿物的结合能力要强于植物源溶解性有机碳与矿物的结合能力[49,53]。然而,试验证据已经表明:矿物结合有机碳中,微生物源有机碳仅占38%,更多的矿物结合有机碳其实来源于植物[19]。

2.2 土壤微生物碳泵理论框架

土壤微生物既可以通过分解代谢向大气释放碳,又可以通过合成代谢将外源碳转化成某种物质形式储存于土壤中[54]。其中,微生物生物量和自身代谢产物的碳输入过程被抽象凝练为微生物碳泵[54-56]。微生物碳泵驱动的碳循环过程在水域生态系统率先被提出:Jiao等[55-56]于2010年在海洋生态系统中正式提出微生物碳泵理论框架,强调海洋微生物可以通过合成代谢将水体中的简单溶解性有机碳转化为复杂的顽固性有机碳,有利于海洋稳定有机碳库的形成。Lu等[57]将微生物碳泵理论框架整合到海洋碳循环模型中,研究了中国南海碳汇对全球气候变化的响应。

在以上背景下,Liang等[50]在2017年提出了土壤微生物碳泵理论框架,核心就是由土壤微生物碳泵介导并参与的土壤有机碳的形成机制,主要包括土壤微生物对植物源碳转化的双重调控途径(植物源碳的转化)、微生物碳泵(土壤微生物源碳的生成)和续埋效应(土壤微生物源碳的稳定化)3方面内容。梁超和朱雪峰[58]最近也进一步详细阐述了土壤微生物碳泵介导的储碳机制及其影响因素。由此可见:尽管微生物效率−基质稳定理论和土壤微生物碳泵理论表述不尽相同,但是核心内涵基本相似,均强调了微生物分解者对植物源有机碳分解的修饰过滤作用,自身代谢产物和死亡残体(本质为微生物的碳利用效率)对有机碳累积的贡献以及矿物对有机碳的保护作用(图2)。

![]() 图 2 土壤有机碳的形成和稳定机制cPOC. 粗颗粒有机碳;fPOC. 细颗粒有机碳;DOC. 溶解性有机碳;MBC. 微生物生物量碳;MAOC. 矿物结合有机碳。下同。cPOC, coarse particulate organic carbon; fPOC, fine particulate organic carbon; DOC, dissolved organic carbon; MBC, microbial biomass carbon; MAOC, mineral-associated organic carbon. The same below.Figure 2. Mechanisms of soil organic carbon formation and stabilization

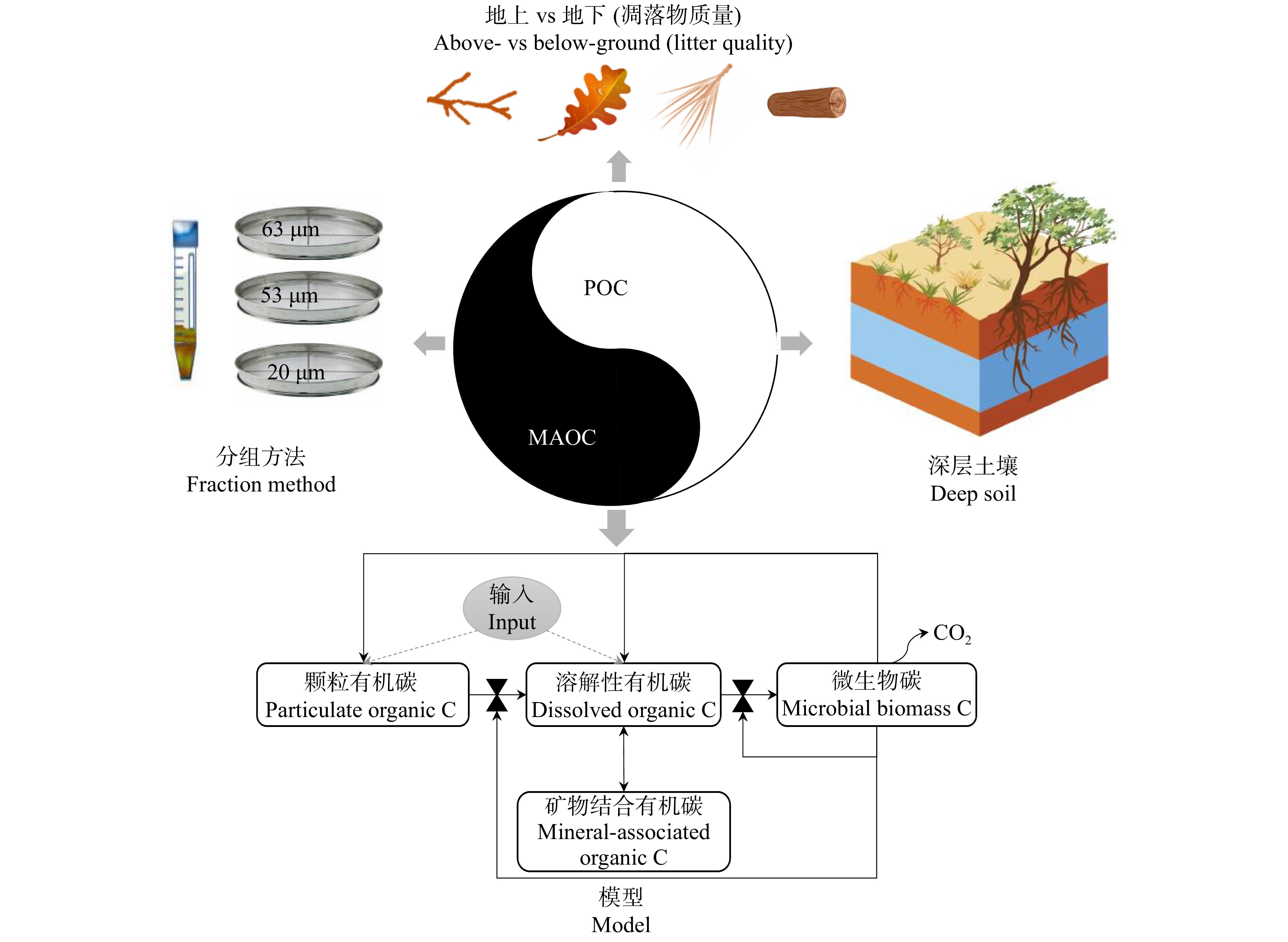

图 2 土壤有机碳的形成和稳定机制cPOC. 粗颗粒有机碳;fPOC. 细颗粒有机碳;DOC. 溶解性有机碳;MBC. 微生物生物量碳;MAOC. 矿物结合有机碳。下同。cPOC, coarse particulate organic carbon; fPOC, fine particulate organic carbon; DOC, dissolved organic carbon; MBC, microbial biomass carbon; MAOC, mineral-associated organic carbon. The same below.Figure 2. Mechanisms of soil organic carbon formation and stabilization虽然土壤有机碳是一个连续体,但土壤某一功能的表现,往往是由一类具有相似的化学成分、结构特征和功能基团的化学混合物同时作用的结果[59]。因此,建立科学合理的土壤有机碳分组(碳库划分)方法,对于土壤碳循环试验和模型研究均具有重要意义[59-60]。关于有机碳组分的物理、化学和生物划分方法非常多,张丽敏等[61]、胡慧蓉等[59]和张国等[62]已经进行了详细总结和回顾。然而,最近几年越来越多的学者建议根据上述土壤有机碳的形成和稳定机制将土壤有机碳分离成颗粒有机碳和矿物结合有机碳[16-18,63-64]。这2种有机碳在形成、稳定性和功能方面存在根本不同(表1)。颗粒有机碳主要来源是植物残体和真菌菌丝的高分子量有机碳,而矿物结合有机碳的主要来源是植物和微生物残体解聚后的小分子有机碳。与颗粒有机碳相比,矿物结合有机碳的密度更大,温度敏感性低,周转时间长。颗粒有机碳的稳定性主要依赖于生化难分解性和团聚体保护,而矿物结合有机碳稳定性主要依赖于矿物保护和团聚体保护。矿物结合有机碳库的大小依赖于其矿物数量、表面积和配体数量,其具有碳库上限,然而颗粒有机碳并不具有碳库上限[51]。

表 1 颗粒有机碳和矿物结合有机碳功能特性Table 1. Functional traits of particulate organic carbon and mineral-associated organic carbon项目

Item颗粒有机碳

Particulate organic carbon矿物结合有机碳

Mineral-associated organic carbon主要来源

Main source植物残体和真菌菌丝

Plant residues and fungal hyphae植物和微生物残体

Plant and microbial residues分子量 Molecular mass/Da > 600 ~ 1 000 < 600 ~ 1 000 密度 Density 低 Low 高 High 碳库上限 Upper limit of C pool 无 No 有 Yes 主要稳定机制

Main stabilization mechanism生化难分解性和团聚体保护

Biochemical recalcitrance and aggregate protection矿物保护和团聚体保护

Mineral and aggregate protection温度敏感性 Temperature sensitivity 高 High 低 Low 周转时间 Turnover time < 10年 ~ 数十年 < ten years – decades 数十年 ~ 数百年 Decades – centuries 3. 土壤碳循环模拟

碳循环模型是预测土壤有机碳对未来气候变化响应的关键手段,但目前众多地球系统模式对土壤有机碳循环的模拟和预测存在巨大的不确定性[60,65]。例如:Todd-Brown等[66]评估了11个主要土壤碳循环模型的模拟精度,结果发现11个模型之间有机碳变化范围达到510 ~ 3 040 Pg,和全球1 m深度土壤碳储量的观测结果差别巨大(1 260 Pg)。Todd-Brown等[67]进一步研究发现:不同模型预测显示2090—2099年和1997—2006年两个阶段的土壤有机碳变化范围为丢失72 Pg到增加253 Pg。导致模型间模拟差异的3个主要原因是模型结构、模型参数和初始条件[68]。

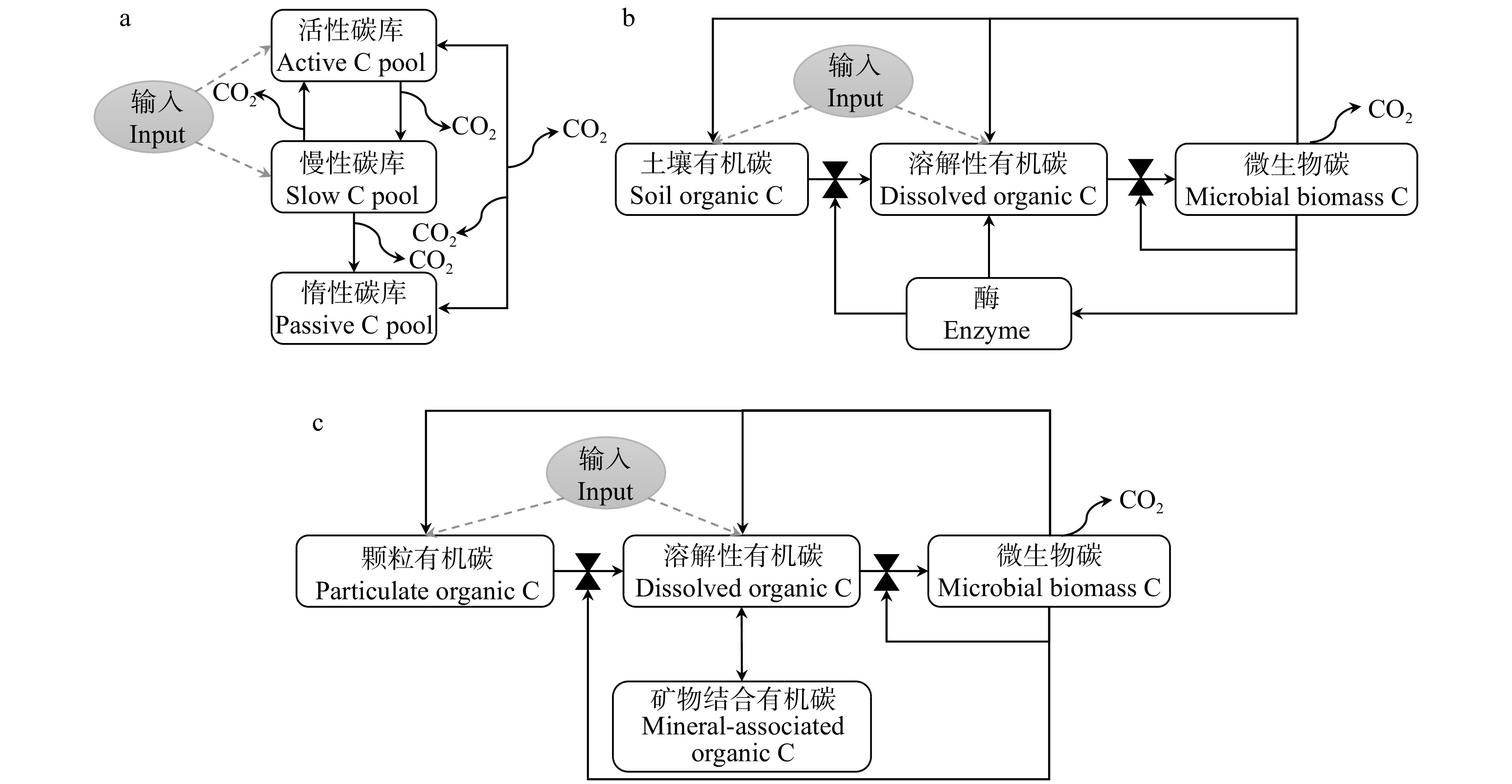

目前对土壤碳循环过程认识的不足是导致模型间结构差异的重要原因。此外,很多模型中的土壤碳库无法通过试验手段进行分离,进而导致传统模型的很多参数无法通过试验进行量化[60]。例如:经典的Century模型基于土壤有机碳的化学顽固性将有机碳划分为活性有机碳库、慢性有机碳库和惰性有机碳库[69](图3),这也是目前绝大多数陆地生态系统模型采用的碳库划分方法,例如:群落陆地模型(community land model,CLM)[70]、陆地生态系统模型(terrestrial ecosystem,TECO)[71]、大气和生物圈土地交换模型(atmosphere and biosphere land exchange,CABLE)[72]等。Schimel和Weintraub[54]首次构建微生物模型后(图3),越来越多的学者均认为将微生物生理特征整合进入碳循环模型是提高土壤碳循环模拟精度的关键手段[73-74]。

随着微生物效率−基质稳定和土壤微生物碳泵理论框架的先后提出,科学家已经尝试将土壤有机碳的真实形成过程、微生物残体碳输入和有机碳的矿物保护机制整合进土壤碳循环模型。例如:基于微生物碳泵框架,Fan等[53]最近将微生物残体碳库纳入土壤碳循环(Michaelis-Menten necromass decomposition,MIND)模型中。然而,MIND模型假设所有的矿物保护有机碳均来自微生物残体,而忽略了植物源有机碳和矿物的结合。然而,有证据表明矿物结合有机碳中微生物源有机碳仅占38%,更多的矿物结合有机碳来源于植物[19]。Millennial模型[75]纳入了植物源有机碳对矿物结合有机碳库的贡献,但却没有考虑微生物残体对颗粒有机碳的贡献,这也违背了试验测定结果[19,76]。COMISSION模型考虑了上述所有过程,但是却忽略了矿物结合有机碳库自身的分解(图3)[77],这与试验观测到的矿物结合有机碳的缓慢分解不符[78]。

沿着土壤剖面,碳输入、土壤质地、温湿度、氧气、微生物群落等因素都会发生显著变化,必然导致土壤有机碳组分和各个组分的分解速率都不相同[79]。垂直方向上的土壤有机碳转运的驱动因素主要有生物扰动、淋溶和扩散(图2)。生物扰动包括诸如蚯蚓等土壤动物的活动引起的有机碳转移。最新研究发现:深层土壤真菌可以将菌丝延伸到表层的凋落叶中,分解吸收有机碳并转运到深层土壤中,贡献深层土壤的有机碳积累[36]。降水引起的土壤溶解性有机碳会通过淋溶方式向深层运输。因此,土壤有机碳的垂直转运过程也是影响模型模拟精度的关键因素[68,80]。目前,CLM[80]、微生物−矿物稳定(microbial-mineral carbon stabilization,MIMICS)[81]和COMISSION[77]等模型均已纳入土壤有机碳的垂直转运。

模型参数也是影响模型精度的重要因素。目前绝大多数模型的模型参数都被设定为固定值,通过添加一定的环境控制因子来约束不同环境条件下的碳循环速率。例如,在CLM模型中,有机碳的分解速率受到温度、水分、氧气和土壤层次的控制[80]。然而,除了这些因子,土壤有机碳分解还受到非常多的、我们无法测定的和不清楚的因子控制[65]。因此,不可能无限的向模型中添加模型参数[65]。为了解决以上问题,一方面,需要通过试验手段测定关键碳循环过程参数,直接为模型提供真实的参数;另一方面,可以利用数据−模型融合技术通过贝叶斯反演方法获取最优模型参数,提高模型的预测精度[82]。总之,目前亟需基于土壤有机碳循环的前沿理论对土壤碳循环模型进行完善和改进,构建可以通过试验数据对模型参数和过程进行直接验证的模型,同时需要权衡模型的复杂性,进而提升模型对土壤碳循环的模拟和预测精度。

4. 展 望

(1)制定国际统一的颗粒有机碳和矿物结合有机碳的分级方法。目前不同研究中颗粒有机碳和矿物结合有机碳的分级方法并不相同,这给不同研究之间的比较带来不确定性(图4)。目前的矿物结合有机碳有重液浮选(密度分组)和湿筛法2大类[59]。密度划分中,重组有机碳被当作矿物结合有机碳。然而,不同研究中使用的重液密度并不相同,经常使用的重液密度为1.6、1.8和2.0 g/cm3[59]。湿筛法中有的研究将20 μm以下的土壤颗粒当作矿物结合有机碳[83],有的将53 μm以下的颗粒当作矿物结合有机碳[84],另外一些却将63 μm以下的颗粒当作矿物结合有机碳[85]。此外,不同研究使用的分散方法和分散剂也不相同[59]。Stewart等[86-87]还构建了物理−化学联合分组方法,即,结合重液浮选、湿筛、玻璃珠分散和酸解等一体的复杂分组方法。总之,未来有机碳分组一方面要最大程度的反映有机碳的功能和组分,同时也应该兼具操作简单性。

(2)植物碳和土壤有机碳之间的联系是陆地碳循环中最不为人所知和充满争议的部分(图4)。传统观点认为生化难分解性高的低质量凋落物有利于有机碳的积累和稳定,而微生物效率−基质稳定假说却认为生化难分解性低的高质量凋落物有利于有机碳的积累和稳定。但Castellano等[51]却认为凋落物质量和有机碳的积累和稳定并没有强烈的相关性。笔者推测土壤中的矿物结合有机碳稳定性可能主要与土壤本身的矿物组成相关,凋落物质量高低决定着颗粒有机碳的稳定性。尽管颗粒有机碳稳定性远远低于矿物结合有机碳的稳定性,然而在土壤风化程度低的北方森林,颗粒有机碳对土壤有机碳的贡献超过一半[57]。因此,有必要研究凋落物质量对土壤有机碳尤其是颗粒有机碳稳定性的调控作用。

(3)植物地下和地上碳输入对土壤有机碳库的相对贡献存在很大的不确定性(图4)。就地下碳输入而言,Xia等[88]在北美五大湖区4个不同纬度阔叶林的研究发现细根凋落物对土壤顽固性有机碳的输入量是地上凋落叶输入量的2倍以上。根系分泌物能消耗5% ~ 10%的净光合产物,也是土壤碳库的重要输入[89]。根系除了直接通过根系表面输入碳外,还可以通过菌根真菌菌丝向土壤输入,其输入量甚至超过了根系表面的直接输入[90-91]。目前根系分泌物的收集方法均未考虑菌根真菌菌丝的碳释放量[92],导致目前低估了根系分泌物的碳输入。Sokol等[93]在美国康涅狄格州的温带森林的研究发现:根系分泌物对颗粒有机碳的贡献是凋落物贡献的2.5倍,其对矿物结合有机碳的贡献是凋落物贡献的2倍。但根系分泌物的碳输入是一把双刃剑,在贡献“新碳”累积的同时也会通过激发效应导致“老碳”分解[94]。气候变化会显著改变植物地上地下碳输入的比例以及根系分泌物[95-96]。因此,精确预测气候变化对土壤碳储量的影响需要精确评估地上和地下碳输入对土壤有机碳的相对贡献,尤其是在颗粒有机碳和矿物保护有机碳中的分配。

(4)陆地生态系统深层土壤碳储量占土壤碳储量60%以上[8]。由于关注较少,长期以来假设深层土壤比表层土壤更加稳定[97]。然而,全剖面研究却发现深层土壤碳循环对气候变化的敏感性甚至高于表层土壤[98-99]。虽然近年来开始关注深层土壤碳循环,但深层土壤仍然是一个鲜为人知的生态系统[100-101]。深入研究深层土壤有机碳的来源、特征与动态对促进土壤固碳科学的发展具有重要意义[97] (图4)。

(5)矿物结合有机碳对温度升高的响应可能没有颗粒有机碳敏感,目前的很多碳循环模型都忽略了矿物对有机碳的长期固持作用,从而会高估全球变暖引起的土壤有机碳流失[102]。总之,新一代土壤碳循环模型结构应该符合土壤有机碳形成和稳定的真实过程(图4),包括可测量碳库、过程参数、微生物生理生态特征和垂直转运,尤其应该将矿物结合有机碳库整合进入模型[19,64,103]。

-

图 1 土壤有机碳的矿物保护和团聚体保护

a. 矿物保护机制;b,c. 干旱和湿润条件下土壤团聚体间的隔离情况,参考Wilpiszeski等[34]绘制;d. 团聚体孔隙对有机碳的闭蓄保护作用(图片来源于Schlüter等[35]);e. 新鲜凋落物−矿物界面(电镜扫描照片来源于Witzgall等[36])。a, mechanisms of mineral protection; b and c, the isolation of soil aggregates under dry and wet conditions, referring to Wilpiszeski, et al.[34]; d, occlusion of soil organic carbon by aggregation (image from Schlüter, et al.[35]); e, scanning electron microscopy image of the interface of plant litter and soil minerals (image from Witzgall, et al.[36]).

Figure 1. Mineral and aggregate protection of soil organic carbon

图 2 土壤有机碳的形成和稳定机制

cPOC. 粗颗粒有机碳;fPOC. 细颗粒有机碳;DOC. 溶解性有机碳;MBC. 微生物生物量碳;MAOC. 矿物结合有机碳。下同。cPOC, coarse particulate organic carbon; fPOC, fine particulate organic carbon; DOC, dissolved organic carbon; MBC, microbial biomass carbon; MAOC, mineral-associated organic carbon. The same below.

Figure 2. Mechanisms of soil organic carbon formation and stabilization

表 1 颗粒有机碳和矿物结合有机碳功能特性

Table 1 Functional traits of particulate organic carbon and mineral-associated organic carbon

项目

Item颗粒有机碳

Particulate organic carbon矿物结合有机碳

Mineral-associated organic carbon主要来源

Main source植物残体和真菌菌丝

Plant residues and fungal hyphae植物和微生物残体

Plant and microbial residues分子量 Molecular mass/Da > 600 ~ 1 000 < 600 ~ 1 000 密度 Density 低 Low 高 High 碳库上限 Upper limit of C pool 无 No 有 Yes 主要稳定机制

Main stabilization mechanism生化难分解性和团聚体保护

Biochemical recalcitrance and aggregate protection矿物保护和团聚体保护

Mineral and aggregate protection温度敏感性 Temperature sensitivity 高 High 低 Low 周转时间 Turnover time < 10年 ~ 数十年 < ten years – decades 数十年 ~ 数百年 Decades – centuries -

[1] Wiesmeier M, Urbanski L, Hobley E, et al. Soil organic carbon storage as a key function of soils-a review of drivers and indicators at various scales[J]. Geoderma, 2019, 333: 149−162. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.07.026

[2] Wall D H, Nielsen U N, Six J. Soil biodiversity and human health[J]. Nature, 2015, 528: 69−76. doi: 10.1038/nature15744

[3] Schmidt M W I, Torn M S, Abiven S, et al. Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property[J]. Nature, 2011, 478: 49−56. doi: 10.1038/nature10386

[4] Li X G, Li F M, Zed R, et al. Soil physical properties and their relations to organic carbon pools as affected by land use in an alpine pastureland[J]. Geoderma, 2007, 139(1−2): 98−105.

[5] Tiessen H, Cuevas E, Chacon P. The role of soil organic matter in sustaining soil fertility[J]. Nature, 1994, 371: 783−785. doi: 10.1038/371783a0

[6] O’rourke S M, Angers D A, Holden N M, et al. Soil organic carbon across scales[J]. Global Change Biology, 2015, 21(10): 3561−3574. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12959

[7] Laban P, Metternicht G, Davies J. Soil biodiversity and soil organic carbon: keeping drylands alive[M]. Gland: IUCN, 2018.

[8] Batjes N H. Harmonized soil property values for broad-scale modelling (WISE30sec) with estimates of global soil carbon stocks[J]. Geoderma, 2016, 269: 61−68. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.01.034

[9] Bossio D A, Cook-Patton S C, Ellis P W, et al. The role of soil carbon in natural climate solutions[J]. Nature Sustainability, 2020, 3(5): 391−398. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0491-z

[10] Beillouin D, Cardinael R, Berre D, et al. A global overview of studies about land management, land-use change, and climate change effects on soil organic carbon[J]. Global Change Biology, 2022, 28(4): 1690−1702. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15998

[11] Sollins P, Homann P, Caldwell B A. Stabilization and destabilization of soil organic matter: mechanisms and controls[J]. Geoderma, 1996, 74(1−2): 65−105. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7061(96)00036-5

[12] Grigatti M, Perez M D, Blok W J, et al. A standardized method for the determination of the intrinsic carbon and nitrogen mineralization capacity of natural organic matter sources[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2007, 39(7): 1493−1503. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.12.035

[13] Feng W T, Shi Z, Jiang J, et al. Methodological uncertainty in estimating carbon turnover times of soil fractions[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2016, 100: 118−124. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.06.003

[14] von Lützow M, Kogel-Knabner I, Ekschmitt K, et al. Stabilization of organic matter in temperate soils: mechanisms and their relevance under different soil conditions: a review[J]. European Journal of Soil Science, 2006, 57(4): 426−445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2389.2006.00809.x

[15] Mayer L M. The inertness of being organic[J]. Marine Chemistry, 2004, 92(1−4): 135−140. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2004.06.022

[16] Sokol N W, Sanderman J, Bradford M A. Pathways of mineral-associated soil organic matter formation: integrating the role of plant carbon source, chemistry, and point of entry[J]. Global Change Biology, 2019, 25(1): 12−24. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14482

[17] Lavallee J M, Soong J L, Cotrufo M F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century[J]. Global Change Biology, 2020, 26(1): 261−273. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14859

[18] Lugato E, Lavallee J M, Haddix M L, et al. Different climate sensitivity of particulate and mineral-associated soil organic matter[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2021, 14(5): 295−300. doi: 10.1038/s41561-021-00744-x

[19] Angst G, Mueller K E, Nierop K G J, et al. Plant- or microbial-derived? a review on the molecular composition of stabilized soil organic matter[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2021, 156: 108189. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108189

[20] Lehmann J, Hansel C M, Kaiser C, et al. Persistence of soil organic carbon caused by functional complexity[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2020, 13(8): 529−534. doi: 10.1038/s41561-020-0612-3

[21] Han L F, Sun K, Jin J, et al. Some concepts of soil organic carbon characteristics and mineral interaction from a review of literature[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2016, 94: 107−121. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.11.023

[22] Feng X J, Simpson M J. The distribution and degradation of biomarkers in Alberta grassland soil profiles[J]. Organic Geochemistry, 2007, 38(9): 1558−1570. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2007.05.001

[23] Lehmann J, Kleber M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter[J]. Nature, 2015, 528: 60−68. doi: 10.1038/nature16069

[24] Melillo J M, Aber J D, Muratore J F. Nitrogen and lignin control of hardwood leaf litter decomposition dynamics[J]. Ecology, 1982, 63(3): 621−626. doi: 10.2307/1936780

[25] Otto A, Simpson M J. Degradation and preservation of vascular plant–derived biomarkers in grassland and forest soils from Western Canada[J]. Biogeochemistry, 2005, 74(3): 377−409. doi: 10.1007/s10533-004-5834-8

[26] Otto A, Simpson M J. Sources and composition of hydrolysable aliphatic lipids and phenols in soils from western Canada[J]. Organic Geochemistry, 2006, 37(4): 385−407. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2005.12.011

[27] Amelung W. Methods using amino sugars as markers for microbial residues in soil[M]//Assessment methods for soil carbon. Boca Raton: Lewis Publishers, 2001.

[28] Gunina A, Kuzyakov Y. From energy to (soil organic) matter[J]. Global Change Biology, 2022, 28(7): 2169−2182. doi: 10.1111/gcb.16071

[29] Wattel-Koekkoek E J W, Buurman P, van der Plicht J, et al. Mean residence time of soil organic matter associated with kaolinite and smectite[J]. European Journal of Soil Science, 2003, 54(2): 269−278. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.00512.x

[30] Kleber M, Bourg I C, Coward E K, et al. Dynamic interactions at the mineral-organic matter interface[J]. Nature Reviews Earth and Environment, 2021, 2(6): 402−421. doi: 10.1038/s43017-021-00162-y

[31] del Nero M, Galindo C, Bucher G, et al. Speciation of oxalate at corundum colloid-solution interfaces and its effect on colloid aggregation under conditions relevant to freshwaters[J]. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2013, 418: 165−173.

[32] Kunhi M Y, Kučerík J, Diehl D, et al. Cation-mediated cross-linking in natural organic matter: a review[J]. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/technology, 2012, 11(1): 41−54. doi: 10.1007/s11157-011-9258-3

[33] Keiluweit M, Kleber M. Molecular-level interactions in soils and sediments: the role of aromatic π-systems[J]. Environmental Science and Technology, 2009, 43(10): 3421−3429. doi: 10.1021/es8033044

[34] Wilpiszeski R L, Aufrecht J A, Retterer S T, et al. Soil aggregate microbial communities: towards understanding microbiome interactions at biologically relevant scales[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2019, 85(14): e00324−19.

[35] Schlüter S, Leuther F, Albrecht L, et al. Microscale carbon distribution around pores and particulate organic matter varies with soil moisture regime[J]. Nature Communications, 2022, 13(1): 1−14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27699-2

[36] Witzgall K, Vidal A, Schubert D I, et al. Particulate organic matter as a functional soil component for persistent soil organic carbon[J]. Nature Communications, 2021, 12(1): 4115. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24192-8

[37] Ni J, Pignatello J J. Charge-assisted hydrogen bonding as a cohesive force in soil organic matter: water solubility enhancement by addition of simple carboxylic acids[J]. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 2018, 20(9): 1225−1233. doi: 10.1039/C8EM00255J

[38] Rowley M C, Grand S, Verrecchia É P. Calcium-mediated stabilisation of soil organic carbon[J]. Biogeochemistry, 2018, 137(1): 27−49.

[39] Totsche K U, Amelung W, Gerzabek M H, et al. Microaggregates in soils[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 2018, 181(1): 104−136. doi: 10.1002/jpln.201600451

[40] Kaiser K, Guggenberger G. Sorptive stabilization of organic matter by microporous goethite: sorption into small pores vs. surface complexation[J]. European Journal of Soil Science, 2007, 58(1): 45−59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2389.2006.00799.x

[41] Mayer L M, Schick L L, Hardy K R, et al. Organic matter in small mesopores in sediments and soils[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2004, 68(19): 3863−3872. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2004.03.019

[42] Mayer L M. Surface area control of organic carbon accumulation in continental shelf sediments[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1994, 58(4): 1271−1284. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(94)90381-6

[43] 刘红梅, 李睿颖, 高晶晶, 等. 保护性耕作对土壤团聚体及微生物学特性的影响研究进展[J]. 生态环境学报, 2020, 29(6): 1277−1284. doi: 10.16258/j.cnki.1674-5906.2020.06.025 Liu H M, Li R Y, Gao J J, et al. Research progress on the effects of conservation tillage on soil aggregates and microbiological characteristics[J]. Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 2020, 29(6): 1277−1284. doi: 10.16258/j.cnki.1674-5906.2020.06.025

[44] Ranjard L, Poly F, Combrisson J, et al. Heterogeneous cell density and genetic structure of bacterial pools associated with various soil microenvironments as determined by enumeration and DNA fingerprinting approach (RISA)[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2000, 39(4): 263−272.

[45] Young I M, Crawford J W. Interactions and self-organization in the soil-microbe complex[J]. Science, 2004, 304: 1634−1637. doi: 10.1126/science.1097394

[46] Barreto R C, Madari B E, Maddock J E L, et al. The impact of soil management on aggregation, carbon stabilization and carbon loss as CO2 in the surface layer of a Rhodic Ferralsol in Southern Brazil[J]. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 2009, 132(3−4): 243−251. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2009.04.008

[47] Sexstone A J, Revsbech N P, Parkin T B, et al. Direct measurement of oxygen profiles and denitrification rates in soil aggregates[J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 1985, 49(3): 645−651. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1985.03615995004900030024x

[48] Wang B, An S, Liang C, et al. Microbial necromass as the source of soil organic carbon in global ecosystems[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2021, 162: 108422. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108422

[49] Cotrufo M F, Wallenstein M D, Boot C M, et al. The microbial efficiency-matrix stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter?[J]. Global Change Biology, 2013, 19(4): 988−995. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12113

[50] Liang C, Schimel J P, Jastrow J D. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2017, 2: 17105. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.105

[51] Castellano M J, Mueller K E, Olk D C, et al. Integrating plant litter quality, soil organic matter stabilization, and the carbon saturation concept[J]. Global Change Biology, 2015, 21(9): 3200−3209. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12982

[52] Hedges J I, Oades J M. Comparative organic geochemistries of soils and marine sediments[J]. Organic Geochemistry, 1997, 27(7−8): 319−361. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(97)00056-9

[53] Fan X, Gao D, Zhao C, et al. Improved model simulation of soil carbon cycling by representing the microbially derived organic carbon pool[J]. The ISME Journal, 2021, 15(8): 2248−2263. doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-00914-0

[54] Schimel J P, Weintraub M N. The implications of exoenzyme activity on microbial carbon and nitrogen limitation in soil: a theoretical model[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2003, 35(4): 549−563. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(03)00015-4

[55] Jiao N, Herndl G J, Hansell D A, et al. Microbial production of recalcitrant dissolved organic matter: long-term carbon storage in the global ocean[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2010, 8: 593−599. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2386

[56] Jiao N, Herndl G J, Hansell D A, et al. The microbial carbon pump and the oceanic recalcitrant dissolved organic matter pool[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2011, 9: 555.

[57] Lu W, Luo Y, Yan X, et al. Modeling the contribution of the microbial carbon pump to carbon sequestration in the South China Sea[J]. Science China Earth Sciences, 2018, 61(11): 1594−1604. doi: 10.1007/s11430-017-9180-y

[58] 梁超, 朱雪峰. 土壤微生物碳泵储碳机制概论[J]. 中国科学: 地球科学, 2021, 51(5): 680−695. Liang C, Zhu X F. The soil microbial carbon pump as a new concept for terrestrial carbon sequestration[J]. Science China Earth Sciences, 2021, 51(5): 680−695.

[59] 胡慧蓉, 马焕成, 罗承德, 等. 森林土壤有机碳分组及其测定方法[J]. 土壤通报, 2010, 41(4): 1018−1024. doi: 10.19336/j.cnki.trtb.2010.04.049 Hu H R, Ma H C, Luo C D, et al. Forest soil organic carbon fraction and its measure methods[J]. Chinese Journal of Soil Science, 2010, 41(4): 1018−1024. doi: 10.19336/j.cnki.trtb.2010.04.049

[60] Bailey V L, Bond-Lamberty B, de Angelis K, et al. Soil carbon cycling proxies: understanding their critical role in predicting climate change feedbacks[J]. Global Change Biology, 2018, 24(3): 895−905. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13926

[61] 张丽敏, 徐明岗, 娄翼来, 等. 土壤有机碳分组方法概述[J]. 中国土壤与肥料, 2014(4): 1−6. doi: 10.11838/sfsc.20140401 Zhang L M, Xu M G, Lou Y L, et al. Soil organic carbon fractionation methods[J]. Soil and Fertilizer Sciences in China, 2014(4): 1−6. doi: 10.11838/sfsc.20140401

[62] 张国, 曹志平, 胡婵娟. 土壤有机碳分组方法及其在农田生态系统研究中的应用[J]. 应用生态学报, 2011, 22(7): 1921−1930. doi: 10.13287/j.1001-9332.2011.0264 Zhang G, Cao Z P, Hu C J. Soil organic carbon fractionation methods and their applications in farmland ecosystem research: a review[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2011, 22(7): 1921−1930. doi: 10.13287/j.1001-9332.2011.0264

[63] Cotrufo M F, Ranalli M G, Haddix M L, et al. Soil carbon storage informed by particulate and mineral-associated organic matter[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2019, 12: 989−994. doi: 10.1038/s41561-019-0484-6

[64] Sokol N W, Whalen E D, Jilling A, et al. Global distribution, formation and fate of mineral-associated soil organic matter under a changing climate: a trait-based perspective[J]. Functional Ecology, 2022, 36(6): 1411−1429. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.14040

[65] Luo Y, Schuur E A G. Model parameterization to represent processes at unresolved scales and changing properties of evolving systems[J]. Global Change Biology, 2020, 26(3): 1109−1117. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14939

[66] Todd-Brown K E O, Randerson J T, Post W M, et al. Causes of variation in soil carbon simulations from CMIP5 earth system models and comparison with observations[J]. Biogeosciences, 2013, 10(3): 1717−1736. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-1717-2013

[67] Todd-Brown K E O, Randerson J T, Hopkins F, et al. Changes in soil organic carbon storage predicted by earth system models during the 21st century[J]. Biogeosciences, 2014, 11(8): 2341−2356. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-2341-2014

[68] Shi Z, Crowell S, Luo Y, et al. Model structures amplify uncertainty in predicted soil carbon responses to climate change[J]. Nature Communications, 2018, 9(1): 2171. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04526-9

[69] Parton W J, Schimel D S, Cole C V, et al. Analysis of factors controlling soil organic matter levels in Great Plains grasslands[J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 1987, 51(5): 1173−1179. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1987.03615995005100050015x

[70] Lawrence D M, Fisher R A, Koven C D, et al. The community land model version 5: description of new features, benchmarking, and impact of forcing uncertainty[J]. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 2019, 11(12): 4245−4287. doi: 10.1029/2018MS001583

[71] Liang J, Xia J, Shi Z, et al. Biotic responses buffer warming-induced soil organic carbon loss in Arctic tundra[J]. Global Change Biology, 2018, 24(10): 4946−4959. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14325

[72] Wang Y P, Law R M, Pak B. A global model of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles for the terrestrial biosphere[J]. Biogeosciences, 2010, 7(7): 2261−2282. doi: 10.5194/bg-7-2261-2010

[73] Wieder W R, Bonan G B, Allison S D. Global soil carbon projections are improved by modelling microbial processes[J]. Nature Climate Change, 2013, 3(10): 909−912. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1951

[74] Allison S D, Wallenstein M D, Bradford M A. Soil-carbon response to warming dependent on microbial physiology[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2010, 3(5): 336−340. doi: 10.1038/ngeo846

[75] Abramoff R Z, Guenet B, Zhang H, et al. Improved global-scale predictions of soil carbon stocks with Millennial Version 2[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2022, 164: 108466. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108466

[76] Six J, Guggenberger G, Paustian K, et al. Sources and composition of soil organic matter fractions between and within soil aggregates[J]. European Journal of Soil Science, 2001, 52(4): 607−618. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2001.00406.x

[77] Ahrens B, Braakhekke M C, Guggenberger G, et al. Contribution of sorption, DOC transport and microbial interactions to the 14C age of a soil organic carbon profile: insights from a calibrated process model[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2015, 88: 390−402. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.06.008

[78] Benbi D K, Boparai A K, Brar K. Decomposition of particulate organic matter is more sensitive to temperature than the mineral associated organic matter[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2014, 70: 183−192. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.12.032

[79] Jobbágy E G, Jackson R B. The vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its relation to climate and vegetation[J]. Ecological Applications, 2000, 10(2): 423−436. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[0423:TVDOSO]2.0.CO;2

[80] Koven C D, Riley W J, Subin Z M, et al. The effect of vertically resolved soil biogeochemistry and alternate soil C and N models on C dynamics of CLM4[J]. Biogeosciences, 2013, 10(11): 7109−7131. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-7109-2013

[81] Wieder W R, Grandy A S, Kallenbach C M, et al. Representing life in the earth system with soil microbial functional traits in the MIMICS model[J]. Geoscientific Model Development, 2015, 8(6): 1789−1808. doi: 10.5194/gmd-8-1789-2015

[82] Huang Y, Lu X, Shi Z, et al. Matrix approach to land carbon cycle modeling: a case study with the Community Land Model[J]. Global Change Biology, 2018, 24(3): 1394−1404. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13948

[83] Angst G, Mueller K E, Eissenstat D M, et al. Soil organic carbon stability in forests: distinct effects of tree species identity and traits[J]. Global Change Biology, 2019, 25(4): 1529−1546. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14548

[84] Samson M É, Chantigny M H, Vanasse A, et al. Coarse mineral-associated organic matter is a pivotal fraction for SOM formation and is sensitive to the quality of organic inputs[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2020, 149: 107935. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107935

[85] Wiseman C L S, Püttmann W. Interactions between mineral phases in the preservation of soil organic matter[J]. Geoderma, 2006, 134(1−2): 109−118. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2005.09.001

[86] Stewart C E, Plante A F, Paustian K, et al. Soil carbon saturation: linking concept and measurable carbon pools[J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2008, 72(2): 379−392. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2007.0104

[87] Stewart C E, Paustian K, Conant R T, et al. Soil carbon saturation: implications for measurable carbon pool dynamics in long-term incubations[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2009, 41(2): 357−366. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.11.011

[88] Xia M, Talhelm A F, Pregitzer K S. Fine roots are the dominant source of recalcitrant plant litter in sugar maple-dominated northern hardwood forests[J]. New Phytologist, 2015, 208(3): 715−726. doi: 10.1111/nph.13494

[89] Farrar J, Hawes M, Jones D, et al. How roots control the flux of carbon to the rhizosphere[J]. Ecology, 2003, 84(4): 827−837. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[0827:HRCTFO]2.0.CO;2

[90] Toljander J F, Lindahl B D, Paul L R, et al. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal mycelial exudates on soil bacterial growth and community structure[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2007, 61(2): 295−304. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00337.x

[91] Frey S D. Mycorrhizal fungi as mediators of soil organic matter dynamics[J]. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2019, 50: 237−259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062331

[92] Vranova V, Rejsek K, Skene K R, et al. Methods of collection of plant root exudates in relation to plant metabolism and purpose: a review[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 2013, 176(2): 175−199. doi: 10.1002/jpln.201000360

[93] Sokol N W, Kuebbing S E, Karlsen-Ayala E, et al. Evidence for the primacy of living root inputs, not root or shoot litter, in forming soil organic carbon[J]. New Phytologist, 2019, 221(1): 233−246. doi: 10.1111/nph.15361

[94] Dijkstra F A, Zhu B, Cheng W. Root effects on soil organic carbon: a double-edged sword[J]. New Phytologist, 2021, 230(1): 60−65. doi: 10.1111/nph.17082

[95] Calvo O C, Franzaring J, Schmid I, et al. Atmospheric CO2 enrichment and drought stress modify root exudation of barley[J]. Global Change Biology, 2017, 23(3): 1292−1304. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13503

[96] Song J, Wan S, Piao S, et al. A meta-analysis of 1, 119 manipulative experiments on terrestrial carbon-cycling responses to global change[J]. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 2019, 3(9): 1309−1320. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0958-3

[97] 周艳翔, 吕茂奎, 谢锦升, 等. 深层土壤有机碳的来源、特征与稳定性[J]. 亚热带资源与环境学报, 2013, 8(1): 48−55. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7105.2013.01.009 Zhou Y X, Lü M K, Xie J S, et al. Sources, characteristics and stability of organic carbon in deep soil[J]. Journal of Subtropical Resources and Environment, 2013, 8(1): 48−55. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7105.2013.01.009

[98] Soong J L, Castanha C, Hicks P C E, et al. Five years of whole-soil warming led to loss of subsoil carbon stocks and increased CO2 efflux[J]. Science Advances, 2021, 7(21): eabd1343. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd1343

[99] Li J, Pei J, Pendall E, et al. Rising temperature may trigger deep soil carbon loss across forest ecosystems[J]. Advanced Science, 2020, 7(19): 2001242. doi: 10.1002/advs.202001242

[100] Kramer M G, Chadwick O A. Climate-driven thresholds in reactive mineral retention of soil carbon at the global scale[J]. Nature Climate Change, 2018, 8(12): 1104−1108. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0341-4

[101] Fontaine S, Barot S, Barré P, et al. Stability of organic carbon in deep soil layers controlled by fresh carbon supply[J]. Nature, 2007, 450: 277−280. doi: 10.1038/nature06275

[102] Tang J, Riley W J. Weaker soil carbon-climate feedbacks resulting from microbial and abiotic interactions[J]. Nature Climate Change, 2015, 5(1): 56−60. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2438

[103] Opfergelt S. The next generation of climate model should account for the evolution of mineral-organic interactions with permafrost thaw[J]. Environmental Research Letters, 2020, 15(9): 091003. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab9a6d

-

期刊类型引用(27)

1. 刘继晨,冯英明,辛荣玉,臧浩,张昊,张明亮,秦华伟,金晓杰. 滨海盐沼湿地土壤有机碳稳定性机制研究进展. 湿地科学与管理. 2025(01): 7-12 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 陈坚淇,贾亚男,贺秋芳,江可,陈畅,叶凯. 不同土地利用方式对岩溶区土壤有机碳组分稳定性的影响. 环境科学. 2024(01): 335-342 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 杨阳,王宝荣,窦艳星,薛志婧,孙慧,王云强,梁超,安韶山. 植物源和微生物源土壤有机碳转化与稳定研究进展. 应用生态学报. 2024(01): 111-123 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 徐凤璟,黄懿梅,黄倩,申继凯. 防护林建设过程中土壤微生物养分限制与有机碳组分之间的关系. 环境科学. 2024(04): 2342-2352 .  百度学术

百度学术

5. 王杰,鞠梦倩,李心月,刘世平. 不同耕作方式与秸秆还田对土壤有机碳和稻麦周年产量的影响. 中国土壤与肥料. 2024(03): 15-22 .  百度学术

百度学术

6. 安立伟,李志刚. 退化荒漠草地恢复对土壤有机碳及其驱动因子的影响. 生态学报. 2024(13): 5519-5531 .  百度学术

百度学术

7. 刘元恭,张彦,谌小慧,陈昭一,童宇毅. 新疆阿尔泰山多年冻土区泥炭剖面有机碳结构变化及其影响机理. 山地学报. 2024(03): 300-311 .  百度学术

百度学术

8. 吴章明,唐思莹,宋思宇,李聪,刘丽鸽,朱鹏,徐红伟,张学强,张健,刘洋. 带状采伐初期对华西雨屏区杉木人工林土壤碳组分及稳定性的影响. 四川农业大学学报. 2024(04): 847-860+878 .  百度学术

百度学术

9. 刘娜,周华. 土壤有机碳分组及测定方法研究概述. 贵州林业科技. 2024(03): 75-81 .  百度学术

百度学术

10. 李娅丽,何国兴,柳小妮,张德罡,徐贺光,纪童,姜佳昌. 陇中黄土高原温性荒漠不同草地型土壤团聚体稳定性及有机碳分布特征. 环境科学. 2024(09): 5431-5440 .  百度学术

百度学术

11. 于远介,张青青,马建国,江康威,李宏. 不同植物群落土壤有机碳及其组分的差异. 中国农业科技导报. 2024(09): 173-182 .  百度学术

百度学术

12. 李金业,程昊,梁晓敏,陈祎霖,武松伟,胡承孝. 酸化土壤改良与固碳研究进展. 生态学报. 2024(17): 7871-7884 .  百度学术

百度学术

13. 白雪娟,翟国庆,刘敬泽. ~(13)C稳定同位素在陆地生态系统植物-微生物-土壤碳循环中的应用. 林业科学. 2024(07): 175-190 .  百度学术

百度学术

14. 郭晓伟,张雨雪,尤业明,孙建新. 凋落物输入对森林土壤有机碳转化与稳定性影响的研究进展. 应用生态学报. 2024(09): 2352-2361 .  百度学术

百度学术

15. 安韶山,胡洋,王宝荣. 黄土高原植被恢复中土壤有机碳稳定机制研究进展. 应用生态学报. 2024(09): 2413-2422 .  百度学术

百度学术

16. 孙瑞丰,韩广轩. 模拟增温对土壤有机碳含量、组分和化学结构的影响:进展与展望. 应用生态学报. 2024(09): 2432-2444 .  百度学术

百度学术

17. 崔宇鸿,叶绍明,卢志锋,燕羽,蒋晨阳. 不同连栽代次桉树人工林土壤团聚体中有机碳组分的积累和转化. 北京林业大学学报. 2024(10): 42-52 .  本站查看

本站查看

18. 陈美镕,王宗松,汪诗平,斯确多吉,周华坤,姜丽丽. 基于文献计量分析植物和微生物驱动的土壤有机碳累积的研究进展. 中国草地学报. 2024(10): 112-123 .  百度学术

百度学术

19. 张金婷,张珊,赵蕾,余冠军,马燕天,吴兰. 湖泊湿地土壤有机碳形成、周转及稳定性研究进展. 生态学报. 2024(20): 8996-9010 .  百度学术

百度学术

20. 石婷,王晋峰,程曼,石娇,李建华,孙楠,王恒飞,徐明岗. “双碳”背景下土壤碳固存研究的演变与最新动态. 山西农业科学. 2024(06): 95-106 .  百度学术

百度学术

21. 艾然,何杰,林海忠,翁丽青,陈照明,马军伟,王强. 不同种植年限茭白田土壤的有机碳含量与结构特征. 浙江农业学报. 2024(11): 2558-2565 .  百度学术

百度学术

22. 李娜,赵娜,王娅琳,魏琳,张骞,郭同庆,王循刚,徐世晓. 高寒人工草地不同植被类型下表层土壤有机碳和无机碳变化及土壤理化因子. 草地学报. 2023(08): 2361-2368 .  百度学术

百度学术

23. 赵广,张扬建. 大气CO_2浓度升高对土壤碳库稳定性的影响. 生态学报. 2023(20): 8493-8503 .  百度学术

百度学术

24. 陈颖洁,房凯,秦书琪,郭彦军,杨元合. 内蒙古温带草地土壤有机碳组分含量和分解速率的空间格局及其影响因素. 植物生态学报. 2023(09): 1245-1255 .  百度学术

百度学术

25. 张睿博,汪金松,王全成,胡健,吴菲,刘宁,高章伟,时蓉喜,刘梦洁,周青平,牛书丽. 土壤颗粒态有机碳与矿物结合态有机碳对气候变暖响应的研究进展. 地理科学进展. 2023(12): 2471-2484 .  百度学术

百度学术

26. 刘娜,周华,张旭,丁访军,彭丽. 黔中不同发育阶段马尾松人工林土壤有机碳组分变化特征. 西部林业科学. 2023(06): 31-38+46 .  百度学术

百度学术

27. 张丽娟,张凤娥,张玉. 干旱胁迫下2种铁线莲幼苗的生理响应. 分子植物育种. 2022(24): 8245-8254 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(41)

下载:

下载: